Beyond Constructivism: Navigationism in the Knowledge Era

advertisement

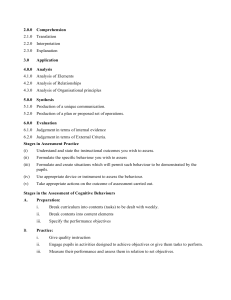

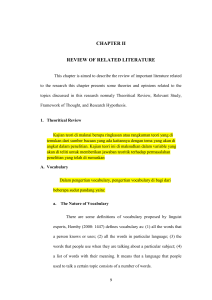

Beyond constructivism: navigationism in the knowledge era Tom H. Brown Tom H. Brown is based in the Department of Telematic Learning & Education Innovation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa Abstract Purpose – This paper seeks to discuss past and present paradigm shifts in education and then to explore possible future learning paradigms in the light of the knowledge explosion in the knowledge era that is currently being entered. Design/methodology/approach – New learning paradigms and paradigm shifts are explored. Findings – Learning processes and learning paradigms are still very much founded in a content-driven and knowledge production paradigm. The rapid developments in information and communication technologies already have and will continue to have a profound impact on information processing, knowledge production and learning paradigms. One needs to acknowledge the increasing role and impact of technology on education and training. One has already experienced enormous challenges in coping with the current overflow of available information. It is difficult to imagine what it will be like when the knowledge economy is in its prime. Practical implications – Institutions should move away from providing content per se to learners. It is necessary to focus on how to enable learners to find, identify, manipulate and evaluate information and knowledge, to integrate this knowledge in their world of work and life, to solve problems and to communicate this knowledge to others. Teachers and trainers should become coaches and mentors within the knowledge era – the source of how to navigate in the ocean of available information and knowledge – and learners should acquire navigating skills for a navigationist learning paradigm. Originality/value – This paper stimulates out-of-the-box thinking about current learning paradigms and educational and training practices. It provides a basis to identify the impact of the new knowledge economy on the way one deals with information and knowledge and how one deals with learning content and content production. It emphasizes that the focus should not be on the creation of knowledge per se, but on how to navigate in the ocean of available knowledge and information. It urges readers to anticipate the on future and to explore alternative and appropriate learning paradigms. Keywords Learning, Knowledge management Paper type Conceptual paper Introduction Educational practice is continually subjected to renewal, due mainly to developments in information and communication technology (ICT), the commercialization and globalization of education, social changes and the pursuit of quality. Of these, the impact of ICT and the new knowledge economy are the most significant. Changes in our educational environment lead, in turn, to changes in our approaches to teaching and learning. These changes also impact on our teaching and learning paradigms. Currently, as over the past few decades, we teach and learn in a constructivist learning paradigm. This article discusses past and present paradigm shifts in education and then explores possible future learning paradigms in the light of the knowledge explosion in the knowledge era that we are currently entering. PAGE 108 j ON THE HORIZON j VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006, pp. 108-120, Q Emerald Group Publishing Limited, ISSN 1074-8121 DOI 10.1108/10748120610690681 The impact of ICT on education The electronic information revolution currently being experienced internationally can be compared to and reveals the same characteristics as the first information revolution started by Gutenberg’s printing press. This implies that, just as present-day society accepts the printing industry as a given and printed materials form an integral part of our daily existence, electronic material will go the same route: Possibly in a drastically shorter period than in the case of printed material. We should acknowledge the increasing role and function of technology in the education environment. Langlois (in Collis, 1999, p. 374) makes the following statement:New information technologies, and particularly the Internet, are dramatically transforming access to information, are changing the learning and research process, how we search, discover, teach and learn . . .Restak (2003, p. 57) points out that, within the modern age, we must be able to rapidly process information, function amidst chaotic surroundings, always remain prepared to shift rapidly from one activity to another and redirect attention between competing tasks without losing time. Currently, as over the past few decades, the majority of our teaching and learning is based upon a constructivist learning paradigm. However, due to the impact of ICT on education, there are a number of issues to interrogate: How will ICT developments impact our educational practice? Will we experience a drastic change in teaching and learning strategies? Will we adopt a new learning paradigm in the next decade or two? These questions lead us to explore new learning paradigms. But before we continue with the exploration, let us look back over recent past decades and review the paradigm shifts we have already experienced. Paradigm shifts in education over recent decades At this stage, it is useful to indicate that the term education be seen as the macro term which includes the concepts teaching and learning (education ¼ teaching þ learning). The most prominent paradigm shifts that we experienced in education during the 20th century are discussed briefly. Reproductive learning vs productive learning Learners’ achievements were measured against their ability to reproduce subject content in other words, how well they could memorize and reproduce the content that the teacher ‘‘transferred’’ to them. With the emphasis on productive learning, it is rather about the application of knowledge and skills, in other words, what the learners can do after completing the learning process. Achievement is measured against the productive contribution a learner can make, instead of what the learner can reproduce. Behaviourism vs constructivism According to a behavioristic view of learning, a learning result is indicated by a change in the behavior of a learner (Skinner, 1938; Venezky and Osin, 1991). According to a constructivist view, learning is seen as the individualized construction of meanings by the learner (Cunningham, 1991; Duffy and Jonassen, 1991). Neither of these views can be regarded as exclusively right or wrong. It is, however, necessary to know that constructivism is presently accepted as the more relevant of the two and that education policies, education models and education practices focus on constructivism. Teacher-centered vs learner-centered In the past, education activities focused on the strong points, preferences and teaching style of the teacher. That which would work best for the teacher, determined the design of the learning environment and the nature of activities. Teacher-centeredness is also characterized by a view that the teacher is the primary source of knowledge for learners. In a learner-centered environment, the focus is on the strong points, preferences and j j VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 ON THE HORIZON PAGE 109 learning style(s) of the learner(s). The learning environment is designed according to the needs and capabilities of the particular learner group. A further distinction between teacher-centeredness and learner-centeredness lies in the responsibility accepted for the learner’s learning process and learning achievement. In a teacher-centered paradigm the teacher accepts this responsibility. Opposed to that, in a learner-centered education paradigm, the learner accepts the full responsibility for his/her own learning. It is for this reason that self-directed learning plays such an important role in effective learner- centered education systems. Note however, that this does not mean that the teacher or educational institution has no responsibility. The focus shifts towards the instructional design of a conducive learning environment, in which effective learning can take place. Teaching-centered vs learning-centered Education activities in the past were planned and executed from a teaching perspective. A teacher would plan a teaching session (lecture) based on what the best teaching methods would be to transfer the relevant subject content to the learners. The focus was on how to teach. In the new paradigm, education activities are planned and executed from a learning perspective. The emphasis is now on the learning activity and learning process of the learner. So the focus is on how the learning, which should take place, can be optimized. ‘‘In general, there must be a conversion from a teaching to a learning culture.’’ (Arnold in Peters, 1999) Teaching vs learning facilitation Teaching or instruction, as an activity of the teacher, is seen as an activity that relates to the ‘‘transfer of content’’ (an objectivist view) within a teaching-centered education paradigm. The presentation/delivery of a lecture or paper falls into this category. The principle of learning facilitation follows a learning-centered education paradigm. Learning facilitation has to do with strategies and activities that focus on optimizing the learner’s learning process. Just as the term indicates, the emphasis is on the facilitation of learning. Teachers cannot be regarded as the only source of knowledge and cannot focus on the traditional ‘‘transfer of content’’ any longer. They need to focus on the facilitation of learning. ‘‘Instructional staff no longer are the fountainhead of information since the technology can provide students with access to an infinite amount of and array of data and information. The role of the instructor, therefore, changes to one of learning facilitator. The instructor assists students to access information, to synthesize and interpret it and to place it in a context – in short to transform information into knowledge.’’ (Kershaw & Safford, 1998, p. 294) Content-based vs outcomes-based A content-driven approach to education is characterized by curriculation and education activities that focus on subject content. The emphasis is on the content that learners should master and a learner receives a qualification based on the nature, amount and level (difficulty) of subject content he/she has mastered. In contrast, an outcomes-based approach to education focuses on the learning outcomes to be reached by the learners. A typical process for curriculation in an outcomes-based model is characterized by the formulation and selection of learning outcomes that a learner should reach - that which the learner must be able to do on completion of the learning process. The selection of subject content is based on the relevance thereof to enable the learner to reach the learning outcomes. Content-based evaluation vs outcomes-based assessment Content-based evaluation follows a reproductive view of learning where a learner’s achievement is measured by the quantity and quality of content that is reproduced. On the contrary, outcomes-based assessment refers to a productive view of learning where a learner’s achievement is measured by the level and extent to which learning outcomes are mastered. j j PAGE 110 ON THE HORIZON VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 Recent developments and trends Some of the more recent developments and trends that have emerged are outlined below. From constructivism to social constructivism Constructivist approaches are now also growing to include social constructivism. Communities of Practice (COPs) are evolving and beginning to play a significant role in teaching and learning environments. The focus is on the effective and productive use of existing, social and natural resources for learning. The real expert is not the teacher, or any other person for that matter, but the community of practice. Constructivism refers to learning as the construction of new meanings (knowledge) by the learner him/herself. Social constructivism refers to learning as the result of active participation in a ‘‘community’’ where new meanings are co-constructed by the learner and his/her ‘‘community’’ and knowledge is the result of consensus (Gruender, 1996; Savery and Duffy, 1995). From knowledge production to knowledge configuration Because of the development in the field of ICT, increasing amounts of information are available and accessible for many people in all parts of the world. The days when knowledge and information were limited to libraries, books and experts, are over. Knowledge production is making room for so-called knowledge configuration. Gibbons (1998, p. i) expresses it as follows: ‘‘Universities have been far more adept at producing knowledge than at drawing creatively (re-configuring) knowledge that is being produced in the distributed knowledge production system. It remains an open question at this time whether they can make the necessary institutional adjustments to become as competent in the latter as they have been in the former.’’ Educational institutions should develop the necessary competent human resources in order to conduct and manage knowledge configuration effectively. ‘‘This requires the creation of a cadre of knowledge workers – people who are expert at configuring knowledge relevant to a wide range of contexts. This new corps of workers is described in the text as problem identifiers, problem solvers, and problem brokers.’’ Gibbons (1998, p. i) Where educational institutions greatly emphasized the generation of content for learning programs in the past, the evaluation, storage and re-use of content will become more important. The generation of certain content might possibly not even happen at or through the institution itself, but elsewhere. The educational institution could possibly, in such a case, give attention to the evaluation, processing and packaging of the content. ‘‘Over 90 percent of the knowledge produced globally is not produced where its use is required. The challenge is how to get knowledge that may have been produced anywhere in the world to the place where it can be used effectively in a particularly problem-solving context.’’ (Gibbons, 1998:i) From knowledge management towards sense making An emerging paradigm shift within management and information sciences suggests that the focus should in future shift from knowledge management to sense making. Snowden (2005) describes sense making as:. . .the way that humans choose between multiple possible explanations of sensory and other input as they seek to conform the phenomenological with the real in order to act in such a way as to determine or respond to the world around them.He then continues to say that it is about ensuring cognitive effectiveness in information processing in order to gain a cognitive edge or advantage. This trend makes a lot of sense when we think about the difficulties we all experience in our daily work and life due to the abundance of information and interaction that requires us to apply new skills in order to manage our environments meaningfully. All these paradigm shifts have contributed to the ever-growing need to innovate our educational practice and to explore new learning paradigms. Cognisance needs to be taken j j VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 ON THE HORIZON PAGE 111 of the fact that ICT developments are impacting educational practice and that we will, in the near future, experience shifts in learning paradigms. Exploring and anticipating future learning paradigms Learning paradigms are already starting to shift beyond the changes experienced in the 20th century in terms of the role of teaching and learning. While the role of the teacher first shifted from ‘‘teaching’’ to ‘‘learning facilitation’’, the latest shift is towards ‘‘facilitated and supported enquiry’’. Soloway (2003), for example, argues that inquiry into authentic questions generated from student experiences is now the central strategy for teaching. The following is a summary of relevant highlights taken from the European Union’s aims for 2010 (Oliveira, 2003): B We should experience a shift from PC centeredness to ambient intelligence. The ICT environment should become personalized for all users. The surrounding environment should be the interface and technology should be almost invisible. There should be infinite bandwidth and full multimedia, with an almost 100 percent online community. B Innovations in learning that we should expect are focused on personalized and adaptive learning, dynamic mentoring systems and integrating experienced based learning into the classroom. Research should be done on new methods and new approaches to learning with ICT. B Learning resources should be digital and adaptable to individual needs and preferences. E-learning platforms should support collaborative learning. There should be a shift from courseware to performanceware focused on professional learning for work. B ICTs should not be an add-on but an integrated part of the learning process. Access to mobile learning should be enhanced through mobile interfaces. These highlights from the EU’s bold but realistic (in first world terms) aims for 2010 provide a couple of indicators for the near future. The knowledge economy and the accompanying commoditization of knowledge and available information, have prompted a further step in the process. Nyiri (2002:2) quotes Marshall McLuhan: The sheer quantity of information conveyed by press-magazines-film-TV-radio far exceeds the quantity of information conveyed by school instruction and texts. This observation does not even mention the magnitude of information freely available on the Internet. Therefore contemporary educational paradigms focus not only on the production of knowledge, but are beginning to focus more and more on the effective application/integration/manipulation/etc. of existing information and knowledge. A new type of literacy is also emerging, namely information navigation. Brown (1999, p. 6) describes this as follows: I believe that the real literacy of tomorrow will have more to do with being able to be your own private, personal reference librarian, one that knows how to navigate through the incredible, confusing, complex information spaces and feel comfortable and located in doing that. So navigation will be a new form of literacy if not the main form of literacy for the 21st century. According to Gartner (2003) the new knowledge economy is merely in its emerging stages and will only reach maturity from 2010 onwards. This is clearly indicated in Figure 1 taken from Gartner (2003). We have already experienced demanding challenges in coping with the current overflow of available information. It is difficult to imagine what it will be like when the knowledge economy is in its prime . . . Knowledge, as codified information, is growing at a phenomenal rate. ‘‘While the world’s codified knowledge base (i.e. all historical information in printed books and electronic files) doubled every 30 years in the earlier part of this century, it was doubling every seven years j j PAGE 112 ON THE HORIZON VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 Figure 1 The rise of the knowledge era (Gartner, 2003) by the 1970s. Information library researchers say that by the year 2010, the world’s codified knowledge will double every 11 hours.’’ (Bontis, 2002, p. 22) Just imagine the extensive information overload we will experience in a situation where the world’s knowledge doubles every 11 hours! Not even to think of the growth after that . . . This future scenario will have a significant impact on information processing (including sense making) and most definitely on our learning processes and learning paradigms that are currently still very much founded in a content and knowledge production paradigm. The authors of the Computing Research Association’s report ‘‘Cyber Infrastructure for Education and Learning for the Future’’, stated that ‘‘the new methodologies of visual analytics will be needed for the analysis of enormous, dynamic, and complex information streams that consist of structured and unstructured text documents, measurements, images, and video. Significant human-computer interaction research will be required to best meet the needs of the various stakeholders.’’ (Computing Research Association, 2005, p. 22) So what will future learning paradigms then look like? To answer this question, we need to explore what lies beyond constructivism. Figure 2 summarizes the paradigm shifts we have experienced in the past and proposes a possible paradigm shift envisaged for the future. A discussion of the paradigm shifts as shown in Figure 2 is presented in Table I It is worrying to observe and difficult to accept that we, as teachers and educationists, are still continuing to work within our ‘‘content-driven’’ paradigms, providing our learners with preselected and carefully designed and developed content. We are heading for a disaster if we are not willing to take the leap out of this fatal paradigm. I argue that navigationism might be the new learning paradigm that lies beyond constructivism. In a navigationist learning paradigm, learners should be able to find, identify, manipulate and evaluate information and knowledge, to integrate this knowledge in their world of work and life, to solve problems and to communicate this knowledge to others. j j VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 ON THE HORIZON PAGE 113 PAGE 114 ON THE HORIZON VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 j j Figure 2 Exploring and anticipating learning paradigms beyond constructivism Table I Discussion of the paradigm shifts as shown in Figure 2 Past The knowledge adoption era: Exploring and anticipating learning paradigms beyond constructivism Present Future The knowledge production era: The knowledge navigation era: During this era the emphasis was on knowledge adoption. Learning activities were focused on studying and memorizing. Successful learning took place when learners mastered the content and rote learning was the means through which this outcome was usually achieved. A change in the behaviour of the learners was the aim of this learning paradigm called behaviourism. In this paradigm, the role of the teacher was to teach. Teaching or instruction was the obvious activity of the master subject expert – the teacher – because he/she was the source of knowledge. The teacher was the ‘‘sage on the stage’’ and the primary source of the WHAT that was to be taught. Knowledge creation was actually only for the élite and it was usually accepted that the knowledge was already there and learners just had to gain the knowledge – thus the focus of learning was on ‘‘gaining’’ knowledge. This is the contemporary learning paradigm where the emphasis is now on knowledge production. Learning activities are focused on inquiry and research. Successful learning takes place when learners are engaged in active learning tasks that guide them to create their own new meanings (knowledge). Productive and experiential learning are the means through which this outcome is usually achieved. The construction of new knowledge is the aim of this learning paradigm called constructivism. In this paradigm, the role of the teacher is to facilitate the learning process. Learning facilitation is the obvious activity of the teacher because he/she is only one of the sources of knowledge. The teacher is the ‘‘guide on the side’’ that allows him to be not only one of the sources of WHAT should be learned, but also the source of HOW to learn. Knowledge production/creation is the central issue of what teaching and learning is about – thus the focus of learning is on ‘‘creating’’/‘‘producing’’ knowledge. In this new learning paradigm that we are already rapidly moving towards, the emphasis will be on knowledge navigation. Learning activities are focused on exploring, connecting, evaluating, manipulating, integrating and navigating. Successful learning takes place when learners solve contextual real life problems through active engagement in problem-solving activities and extensive networking, communication and collaboration. The aim of these activities is not to gain or create knowledge, but to solve problems. Knowledge is, of course, being created in the process, but knowledge creation is not the focus of the activities per se. Navigating skills are required to survive in the knowledge era learning paradigm called navigationism. In this paradigm, the role of the teacher is to coach the learners in HOW to navigate – to be their mentor in the skills and competencies required in the knowledge era. The teacher is the ‘‘coach in touch’’ with the demands and survival skills of the knowledge era. Knowledge navigation is the central issue of what teaching and learning is about – thus the focus of learning is on ‘‘navigating’’ in the ocean of available knowledge. The relation between navigationism and constructivism Constructivism has been the learning paradigm during the past few decades. And social constructivism is in my mind an intermediate or sub-step forward towards a new learning paradigm. I am not claiming that constructivism will no longer be relevant or applicable. Navigationism will not ‘‘replace’’ constructivism or change learning theory completely. A constructivist learning theory will remain within the heart of our learning science, but the focus of our learning activities will shift towards navigationism as the new learning paradigm. In the same way, when the shift from behaviourism to constructivism took place (and is still taking place), it never implied that behaviourism ceased to exist. Behaviourism is an essential part of our learning theory, but it is currently not the focus of our teaching and learning activities. While we are promoting constructivist activities with learners and facilitating the learning process through being the ‘‘guide on the side’’, it doesn’t imply that our learners do not have behaviourist outcomes (change in behaviour) as well. In the same way, constructivist outcomes will remain, but our focus in the knowledge era will shift towards navigationist outcomes. Navigating skills required in a navigationist learning paradigm Technological developments introduced new and alternative views about our interaction with information and people and about the skills and competencies we require to survive in the knowledge era. The most basic skills required are problem solving skills, ICT skills, visual j j VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 ON THE HORIZON PAGE 115 media literacy, e-competence to function within the technological and knowledge era, as well as psychological and emotional competence. Adding to these basic skills, the following are some examples of the skills and competencies required in a navigationist paradigm: B The ability – know-how and know-where – to find relevant and up-to-date information, as well as the skills required to contribute meaningfully to the knowledge production process. This includes the mastery of networking skills and skills required to be part of and contribute meaningfully to communities of practice and communities of learning. This implies that the basic communication, negotiation and social skills should be in place. B The ability to identify, analyse, synthesize and evaluate connections and patterns. B The ability to contextualize and integrate information across different forms of information. B The ability to reconfigure, re-present and communicate information. B The ability to manage information (identify, analyse, organize, classify, assess, evaluate, etc.). B The ability to distinguish between meaningful and irrelevant information for the specific task at hand or problem to be solved. B The ability to distinguish between valid alternate views and fundamentally flawed information. B Sense making and chaos management. Let us explore recent work of a few researchers in the field with a view to identify further navigating skills. In his paper called: ‘‘Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age’’, George Siemens describes connectivism as: ‘‘the integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and complexity and self-organization theories.’’ (Siemens, 2004, p. 5) This is a very useful definition to describe the complex learning environment in the knowledge era. Analyzing the elements and principles of connectivism as described by Siemens, we are able to identify several important skills that learners require within a navigationist learning paradigm. Siemens (2004, p. 5) continues with his description of connectivism by saying that the learning process: ‘‘ . . . is focused on connecting specialized information sets, and the connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing.’’ He also states that: ‘‘connectivism is driven by the understanding that decisions are based on rapidly altering foundations. New information is continually being acquired. The ability to draw distinctions between important and unimportant information is vital. The ability to recognize when new information alters the landscape based on decisions made yesterday is also critical.’’ I fully support this. What Siemens describes here are essential navigating skills for the knowledge era. Let us now have a look at the issue of connectedness. Diana and James Oblinger talk about the Internet Generation as follows: ‘‘As long as they’ve been alive, the world has been a connected place, and more than any preceding generation they have seized on the potential of networked media.’’ While highly mobile, moving from work to classes to recreational activities, the Net Gen is always connected. (Oblinger & Oblinger, 2005, p. 2.5) Constant connectedness is a given circumstantial reality underpinning learning environments in a navigationist paradigm. To ‘‘connect’’ and to be/stay connected is part of the skill to ‘‘navigate’’. I would therefore prefer to view connectivism as a term to describe a connected learning environment in which connectivist learning strategies, learning skills and learning activities are required to learn effectively. Siemens (2004, p. 6) correctly states that: ‘‘Connectivism j j PAGE 116 ON THE HORIZON VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 provides insight into learning skills and tasks needed for learners to flourish in the digital era.’’ Connectivist learning skills are required to learn successfully within a navigationist learning paradigm. Connectivism is part and parcel of navigationism, which is the broader concept comprising more than connectivism, as illustrated in Figure 3. The following list is a selection of Siemens’ principles of connectivism (Siemens, 2004). It provides a summary of the connectivist learning skills and principles required within a navigationist learning paradigm: B Learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources. B Capacity to know more is more critical than what is currently known. B Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning. B Ability to see connections between fields, ideas, and concepts is a core skill. B Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the intent of all connectivist learning activities. B Decision making is itself a learning process. Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is seen through the lens of a shifting reality. While there is a right answer now, it may be wrong tomorrow due to alterations in the information climate affecting the decision. David Passig (2001) explores ICT mediated future thinking skills. His work traces the basic nature of future society and proposes a relevant taxonomy of future cognitive skills with appropriate tools to succeed in the future. Passig states that in the knowledge era there is a need for unique cognitive skills in order to process information successfully in real time. He continues by saying that those who will have the skills of collecting information in real time, as well as the ability to analyse, classify, and organize it, will be those to achieve a social, cultural and economical advantage. (Passig, 2001) It is important to note his statement that most of the intellectual activity will be to ‘‘amplify the value of available information’’ (Passig, 2001). The knowledge age acknowledges the fact that the rate of information overflow will be accelerated, and that the main role of people will be to add value to the exchange of information (Harkins, 1992 and O’Dell, 1998 in Passig, 2001). Passig (2001) uses Bloom’s taxonomy as a working platform and expands the categories to reflect the needs of the future. Passig’s work provides very useful suggestions and insight into the new type of cognitive skills that learners will require in the near future. The following is a meaningful list of navigating skills that can be drawn from the work of Passig: B To know where to find useful information and to master search strategies. B To develop new symbols, codes and conventions. Figure 3 The relation between navigationism and connectivism j j VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 ON THE HORIZON PAGE 117 B To expand existing models of thinking and to create inferences and analogies. B To analyse pieces of information in various ways and to make new connections. B To distinguish relationships between fragments of information and to create new relations. B To evaluate the reliability of information keeping in mind the influence of time, context and personal interpretation. B To locate a separate element out of the pieces of information that it was taken from in order to create a new meaning. B To choose the suitable combination of information and implement it in problem solving in different situations. B To create consonance – an agreement/harmony/accord/personal new logical connection between two domains that seemed distant from each other. B To create association – the mental notion of connection or relation between thoughts, feelings, ideas or sensations. The list of navigating skills and competencies required within a navigationist paradigm that is provided in the preceding paragraphs, is far from complete. What is provided here should be regarded merely as examples. Much research is required to refine the definition and description of a navigationist learning paradigm. The list of skills and competencies should be further developed and refined. Paradigm shifts and role changes Tables II and III provide a concise summary of the past and envisaged educational paradigm shifts, as well as the past and envisaged role changes of role players within teaching and learning environments. Tables II and III also provide a key word summary of the most important issues in the preceding discussions. Table II Summary of paradigm shifts in education Past Paradigm shifts in education Present Future knowledge adoption behaviourism objectivism instruction information gathering knowledge provision knowledge production cognitivism constructivism learning facilitation information generation knowledge management knowledge navigation navigationism connectivism coaching and mentoring information navigation sense making Table III Summary of role changes in education Role changes in education Past Present Knowledge adoption era Knowledge production era Role player Learner Teacher Instructional designer knowledge adoption instruction design of instruction reduction of content knowledge production learning facilitation design of learning facilitation and learning activities re-/configuration of knowledge Information specialist information gathering and provision knowledge provision information configuration knowledge management j j PAGE 118 ON THE HORIZON VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 Future Knowledge navigation era knowledge navigation coaching and mentoring design of coaching and navigating activities configuration of navigation tools information facilitation sense making Conclusion What lies beyond constructivism? Perhaps navigationism? Are we planning for and anticipating the future? Are we ready to take the leap to the next learning paradigm? Or will the ever growing and demanding knowledge era catch us all off guard? Institutions should move away from providing content per se to learners. We should focus on coaching learners to find, identify, manipulate and evaluate information and knowledge, to integrate this knowledge in their world of work and life, to solve problems and to communicate this knowledge to others. Learners should be connected and networking in various ways in the digital age. Teachers and educators should become the source of how to navigate in the ocean of available information and knowledge. We should become coaches and mentors within the knowledge era. Instructional designers should start to design coaching and navigating activities instead of designing learning facilitation and learning activities; to configure navigation tools instead of the re-/configuration of content. May this article stimulate further research to define navigationism and to describe the navigating skills we require to survive in the knowledge era. References Bontis, N. (2002), ‘‘The rising star of the Chief Knowledge Officer’’, Ivey Business Journal, March/April, pp. 20-5. Brown, J.S. (1999), ‘‘Learning, working & playing in the digital age’’, paper presented at the 1999 Conference on Higher Education of the American Association for Higher Education, March, Washington DC. Collis, B. (1999), ‘‘New didactics for university instruction: why and how?’’, Computers & Education, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 373-93, available at: www.sciencedirect.com/science Computing Research Association (2005), ‘‘Cyber infrastructure for education and learning for the future: a vision and research agenda’’, report available at: www.cra.org/reports/cyberinfrastructure.pdf Cunningham, D.J. (1991), ‘‘Assessing constructions and constructing assessments’’, Educational Technology, Vol. 31 No. 5, pp. 13-17. Duffy, T.M. and Jonassen, D.H. (1991), ‘‘Constructivism: new implications for instructional technology?’’, Educational Technology, Vol. 31 No. 5, pp. 7-12. Gartner (2003), ‘‘Emerging technology scenario’’, paper delivered by Gartner analyst Nick Jones at the Gartner Symposium and ITxpo, Cape Town, August 4-6. Gibbons, M. (1998), ‘‘Higher education relevance in the 21st century’’, paper presented at the Unesco World Conference, Paris, October 5-9, pp. i-ii & 1-60. Gruender, C.D. (1996), ‘‘Constructivism and learning: a philosophical appraisal’’, Educational Technology, Vol. 36 No. 3, pp. 21-9. Kershaw, A. and Safford, S. (1998), ‘‘From order to chaos: the impact of educational telecommunications on post-secondary education’’, Higher Education, Vol. 35, pp. 285-98. Nyiri, K. (2002), ‘‘Towards a philosophy of m-learning’’, paper presented at the IEEE international workshop on wireless and mobile technologies in education, August 29-30, Växjö University, Sweden. Oblinger, D.G. and Oblinger, J.L. (Eds) (2005), Educating the Net Generation, an EDUCAUSE eBook available at: www.educause.edu/educatingthenetgen Oliveira, C. (2003), ‘‘Towards a knowledge society’’, keynote address delivered at the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT). Athens, July. Passig, D. (2001), ‘‘A taxonomy of ICT mediated future thinking skills’’, in Taylor, H. and Hogenbirk, P. (Eds), Information and Communication Technologies in Education: The School of the Future, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, MA. j j VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006 ON THE HORIZON PAGE 119 Peters, O. (1999), ‘‘The university of the future – pedagogical perspectives’’, paper presented at the 19th World Conference of the International Council for Open and Distance Education, Vienna, June 19-24. Restak, R.M. (2003), The New Brain: How the Modern Age Is Rewiring Your Mind, Rodale, London. Savery, J.R. and Duffy, T.M. (1995), ‘‘Problem based learning: an instructional model and its constructivist framework’’, Educational Technology, Vol. 35 No. 5, pp. 31-8. Siemens, G. (2004), ‘‘Connectivism: a learning theory for the digital age’’, available from eLearnspace at: www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm Skinner, B.F. (1938), The Behaviour of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis, Longman, New York, NY. Snowden, D.J. (2005), ‘‘Multi-ontology sense making: a new simplicity in decision making’’, Management Today, Yearbook 2005, Vol. 20. Soloway, E. (2003), ‘‘Handheld computing: right time, right place, right idea’’, paper presented at the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), Athens, July. Venezky, R. and Osin, L. (1991), The Intelligent Design of Computer-Assisted Instruction, Longman, New York, NY. About the author Tom H. Brown obtained his PhD in the field of distance learning in 1993 at the University of Pretoria with the topic: ‘‘The operationalisation of metalearning in distance education’’. His expertise is in the following fields: learning, learning facilitation, education innovation, distance learning (ODL), instructional design, educational technology, flexible learning, e-learning and m-learning. He currently holds the position of Deputy Director at the University of Pretoria where he is responsible for, amongst other, educational technology, education innovation and distance education partnerships. Tom is the author of a large number of publications and the international recognition for his work has culminated in numerous invited keynote addresses at international conferences as well as many invited presentations and guest lectures. He is also a visiting expert and guest lecturer in international postgraduate courses in distance education and invited chair of research workshops. Tom H. Brown can be contacted at: [email protected] To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: [email protected] Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints j j PAGE 120 ON THE HORIZON VOL. 14 NO. 3 2006