Uploaded by

trisyaputri90

Traumatic Hyphema in Badminton Players: Eye Protection Mandate?

advertisement

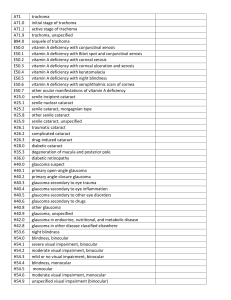

Case Report a half Tegaderm film dressing, which helps to correct and strengthen the initial draping, eliminating the need for a new draping procedure, saving considerable time. Koray Karadayı, MD Near East University School of Medicine, Department of Ophthalmology, Lefkoşa, TRNC, Mersin 10, Turkey. Correspondence to: Koray Karadayi, MD: [email protected] REFERENCES 1. Atchoo P, Hionis M, Cinotti AA. A practical drape for eye surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;75:508-9. Traumatic hyphema in badminton players: should eye protection be mandatory? In Canada, sports account for the majority of injuries limiting daily activity in people between the ages of 12 and 64 years.1 Although most sports injuries are musculoskeletal in nature, sports-related ocular injuries have the potential for significant vision loss and morbidity.1 Eye trauma, often occurring through physical activity, is the leading cause of noncongenital monocular blindness in children.2,3 Blunt trauma accounts for most sportsrelated eye injuries and, depending on the mechanism of injury, can cause many presentations, including hyphema. Traumatic hyphema occurs when a blow to the orbit ruptures blood vessels, supplying the iris and ciliary body, causing entry of blood into the anterior chamber.4 The severity of hyphema can range from microhyphema, a minimal suspension of erythrocytes in the anterior chamber, to total hyphema in which the entire anterior chamber is filled with blood. It is commonly observed as a layer of fresh or clotted blood along the bottom of the chamber. Hyphema can lead to permanent vision loss through secondary glaucoma, optic atrophy, and corneal bloodstaining.2,3,4 Based on statistics collected from 1972 to 2002, the Canadian Ophthalmology Society reports that the most common sports that cause ocular injury in Canada are hockey, racquet sports, and baseball.5 Badminton accounts for the most reported eye injuries compared to all racquet sports combined in Canada.5 Although it is well known that squash balls can cause significant ocular injuries, it is much less known that badminton shuttlecocks can also cause significant permanent vision loss. In this case series, we describe 5 cases of hyphema caused by badminton and review preventative measures to minimize complications in this presentation. 2. Norris JH, Spokes DM, Ball JL. Modified draping technique for topical anaesthesia ophthalmic surgery. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;39:274-5. 3. Fox OJ, Sim BW, Win S, et al. Technique to exclude temporal lash incursion in phacoemulsification surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1885-7. 4. Webster J, Alghamdi A. Use of plastic adhesive drapes during surgery for preventing surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD006353. 5. Yu CQ, Ta CN. Prevention of postcataract endophthalmitis: evidence-based medicine. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:19-25. Can J Ophthalmol 2017;52:e141–e143 0008-4182/17/$-see front matter & 2017 Canadian Ophthalmological Society. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.01.016 METHODS The medical records of patients presenting to the Rockyview General Hospital Urgent Eye Clinic in Calgary from October 2013 to October 2014 were reviewed, and all cases of hyphema caused by badminton were identified. Patient age, sex, time from injury to medical care, mechanism of injury, use of eye protection, ocular and systemic history, presenting visual acuity (VA), intraocular pressure (IOP), hyphema grade (Table 1), associated ocular injuries, treatment, and follow-up were recorded. RESULTS All patients suffered a direct hit to 1 eye from a shuttlecock and presented to clinic within 24 hours of the injury. None were wearing protective eyewear at the time of the injury to medical care. One patient required multiple surgeries, whereas the rest were treated conservatively. Table 2 describes the clinical presentation of each patient immediately after the injury and during the recovery process. Case 1 A 77-year-old male presented to the clinic 1.5 hours after a hit to the right eye. Initial VA was perception of hand motion (HM) OD and 20/20 OS. IOP was too low to be determined in the right eye because of ciliary body shut down. IOP in the left eye was 14 mm Hg. Grade 3 hyphema and subconjunctival hemorrhage (SCH) were Table 1—Traumatic hyphema grading scale3 Grade Hyphema Measurement Microhyphema No layered blood; suspended red blood cells in anterior chamber Grade 1 Blood presenting in less than 1/3 of the anterior chamber Grade 2 Blood occupying 41/3 and o2/3 of the chamber Grade 3 Blood occupying 41/2 of the chamber Grade 4 Blood filling the entire anterior chamber CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. 52, NO. 4, AUGUST 2017 e143 Case Report Table 2—Clinical details of patients Case Age, years Sex Eye Ocular Injuries Postinjury VA Final VA Recovery Time 1 77 M OD HM HM Unresolved (47 months) 2 12 M OS 20/20 20/20 13 days 3 15 F OS 20/25, 1 20/20, 1 28 days 4 5 50 30 M M OD OS Hyphema (grade 3; 5.5 mm), corneal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, nonhealing neurotrophic corneal ulcer Hyphema (grade 1; 0.8 mm), angle closure glaucoma, corneal edema Microhyphema, iris sphincter tears, commotio retinae Hyphema (grade 1; o0.5 mm) Microhyphema 20/20, 2 20/20 20/20, 1 20/30, þ1 3 days 7 days VA, visual acuity; HM, hand motion. observed by slit-lamp examination (SLE). The patient was started on topical prednisolone and activity was restricted. Over 6 days, corneal edema, Descemet membrane folds, and a dense clot over the intraocular lens developed in the right eye. Hyphema was reduced to grade 1; however, VA for the right eye remained at HM. An anterior chamber washout was performed, topical prednisolone was continued, and topical moxifloxacin was prescribed. On the fifth follow-up, brimonidine/timolol and homatropine were started. By 2 weeks, there was no improvement in the VA of the right eye, and a vitreous hemorrhage had developed. Since then, the patient has developed superior and inferior retinal detachments and a nonhealing neurotrophic corneal ulcer in the right eye. vision was reported in the right eye. IOP was 26 mm Hg OD and 21 mm Hg OS. Grade 1 hyphema was observed. Management included topical prednisolone, homatropine, brimonidine/timolol, and activity restriction. Within 2 days, the hyphema had resolved, and VA had fully recovered. Case 5 A 30-year-old male presented to clinic after a hit to the left eye. Initial VA was 20/20 OU. Blurry vision and photophobia were reported in the left eye. Microhyphema and mild conjunctival injection were observed. Management included topical prednisolone and activity restriction. After 1 week, the microhyphema had resolved, and VA was 20/25 OS. Case 2 A 12-year-old male presented to the clinic after a hit to the left eye. Initial VA was 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS. IOP was 18 mm Hg OD and 24 mm Hg OS. Grade 1 hyphema (0.8 mm), conjunctival injection, and an oblong pupil were observed. Management included topical prednisolone and activity restriction. Follow-up after 4 days revealed reduction in the hyphema to 0.2 mm, corneal edema, and a significant increase in IOP to 31 mm Hg in the left eye. VA remained unimproved. Travoprost/ timolol was prescribed alongside prednisolone. Within 2 weeks, the patient recovered full vision, and the hyphema was resolved. Case 3 A 15-year-old female presented to clinic after a hit to the left eye. Initial VA was 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS. IOP was 18 mm Hg OD and 22 mm Hg OS. Microhyphema, iris sphincter tears, pigment dispersion in the anterior chamber, SCH, and commotion retinae were observed on SLE and fundus examination. Management included topical prednisolone, homatropine, and activity restriction. Within 28 days, VA had fully recovered, and the microhyphema had resolved. Case 4 A 50-year-old male presented to clinic after a hit to the right eye. Initial VA was 20/20 OU; however, blurry e144 CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. 52, NO. 4, AUGUST 2017 DISCUSSION Management of traumatic hyphema aims to reduce initial bleeding and prevent secondary hemorrhage and other complications, including secondary glaucoma and corneal bloodstaining.2–6 Secondary hemorrhage, a major complication of hyphema, usually presents 2 to 5 days after the injury and is often of greater magnitude than the initial hyphema, increasing the incidence of secondary glaucoma that could cause irreversible optic nerve damage.2,6,7 Predictors of rebleeds include delayed medical assessment over 24 hours from the injury, an initial hyphema of grade 2 or higher, elevated IOP greater than 21 mm Hg, and an initial VA worse than 20/200.7 Patients with sickle cell disease Table 3—Sight threatening complications from badminton in Malaysia and the Philippines9,10 Number of Cases Type of Injury Hyphema* Iritis Secondary glaucoma* Corneal edema* Macular changes Commotio retinae* Vitreous hemorrhage* Retinal detachment* Chandran (n ¼ 63) 9 Zamora and Uy10 (n ¼ 23) 49 — 4 — 8 12 8 — *Sight threatening complications also present in this case series. 5 11 6 2 2 1 1 1 Case Report have a higher incidence of secondary hemorrhage, glaucoma, and permanent vision loss.2–4,6,7 Retinal damage contributes significantly to poor visual outcomes after trauma although does not often present immediately as visibility may be obscured by the hyphema.8 Few studies exist in reference to badminton-related ocular injuries. Sixty-three cases were assessed at the Eye Clinic of the University Hospital in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, over a period of 5 years.9 Of these cases, 57 were caused by a direct hit from a shuttlecock, and the rest were caused by rackets.9 Of these injuries, traumatic hyphema was the most common presentation, followed by traumatic mydriasis and commotio retinae (Table 3).9 In Malaysia, badminton was found to be the main cause of traumatic hyphema compared to other causes, including other sports, industrial accidents, and other projectiles.9 In this study, 50.8% of cases recovered 20/20 vision; however, 11.0% recovered less than 20/200.9 A cross-sectional survey in the Philippines reported on 23 cases of badminton-related ocular injuries over 6 months in 7 urban eye centres.10 Of these cases, iritis and iridocyclitis were the most common presentations, followed by secondary glaucoma and traumatic hyphema (Table 3).10 Final visual acuities were over 20/40 except for 1 case resulting in a final acuity of less than 20/80.10 In a case series at the Leicester Royal Infirmary, 2 of 6 cases yielded visual acuities of counting fingers and light perception.11 None of the patients in these studies wore protective eyewear at the time of injury.9–11 Over 90% of ocular injuries are preventable with appropriate eye protection, yet studies show low rates of use among athletes.12 In the United States, 84.6% of children do not wear protective eyewear despite engaging in sports that risk eye injury.12 In Australia, a survey of squash players revealed that 18.8% of adults claimed to wear protective eyewear but, of these players, only 9.4% were found to use adequate protection that did not include prescription eyeglasses, open eyeguards, industrial eyewear, and contact lenses.13 Another survey on racquetball players indicated that the leading self-reported reasons for not using goggles were a lack of consideration for the risk of injury, the perception that low-intensity play did not warrant goggle use, cost, and discomfort.14 These findings suggest that exploring the protective eyewear use of patients on history, active education on injury risk, and the recommendation of appropriate protective wear would be beneficial to preventing ocular injury. Many Canadian Badminton Associations do not require players to wear protective eyewear, with the exception of British Columbia, which requires mandatory ASTM F803 protective eyewear for all junior players under the age of 19 years. In Ontario and Nova Scotia, mandatory protective eyewear is required for all junior doubles play, whereas in Newfoundland and Labrador and Northwest Territories it is required for all junior girls only when participating in mixed doubles tournaments. Regulations on protective eyewear vary between Canadian Badminton Associations and Canadian School Boards. Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island School Boards require all students regardless of whether they are single or double players to wear protective eyewear that meet the ASTM F803 standards. The Newfoundland and Labrador School Board requires protective eyewear for all males and females only participating in mixed doubles events; however, students who wear prescription glasses are not required to wear protective eyewear. Both badminton associations and school boards in other provinces only strongly recommend the use of protective eyewear for children and adults. Although ocular injuries most frequently occur during doubles play and with inexperienced players, it is notable that, in 2013, the world’s fastest shuttlecock velocity was recorded to be 493 km/h with the use of increasingly advanced racket technology.9–11,15,16 In consideration of these velocities, strict regulations for singles and experienced players should be explored. In Canada, the evolution of facial protection and implementation of mandatory full-face shields in minor hockey led to a significant decline in ocular injuries.16 Hockey players who do not wear helmets or masks and those wearing only helmets sustained an equal number of ocular injuries. Mandatory helmets and facial protection reduced the number of ocular injuries in 1974–1975 to half of that in 1983–1984.17,18 Additionally, hockey players were 10 times more likely to sustain an ocular injury with no facial protection and 4 times as likely with partial facial protection,19 whereas no injuries were found with full-face protection. Implementation of mandatory full-face protection for minor hockey players has led to a decline in ocular injuries.20 Eye protection should be required in badminton as well, particularly in the education system where young players are learning the sport. Micah Luong, MD, Victoria Dang, BSc, Chris Hanson, MD, FRCSC Division of Ophthalmology, Department of Surgery, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alta. Correspondence to: Micah Luong, MD: [email protected] REFERENCES 1. Statistics Canada. Injuries in Canada: insights from the Canadian Community Health Survey. 2011 (updated 2011 Jun 28, cited 2014 Nov 26). ⟨http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-624-x/2011001/article/ 11506-eng.htm⟩. 2. SooHoo JR, Davies BW, Braverman RS, Enzenauer RW, McCourt EA. Pediatric traumatic hyphema: A review of 138 cases. J AAPOS. 2013;17:565-7. 3. Rocha KM, Martins EN, Melo LA Jr, Moraes NS. Outpatient management of traumatic hyphema in children: Prospective evaluation. J AAPOS. 2004;8:357-61. 4. Gharaibeh A, Savage HI, Scherer RW, Goldberg MF, Lindsley K. Medical interventions for traumatic hyphema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12 CD005431. 5. Canadian National Institute of the Blind. Eye safety: overview. 2014 (cited 2014 Nov 26). ⟨http://www.cnib.ca/en/your-eyes/safety/ at-play/Pages/Overview.aspx⟩. 6. Walton W, Von Hagen S, Grigorian R, Zarbin M. Management of traumatic hyphema. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:297-334. CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. 52, NO. 4, AUGUST 2017 e145 Case Report 7. Stilger VG, Alt JM, Robinson TW. Traumatic hyphema in an intercollegiate baseball player: A case report. J Athl Train. 1999;34:25-8. 8. Ng CS, Sparrow JM, Strong NP, Rosenthal AR. Factors related to the final visual outcome of 425 patients with traumatic hyphema. Eye (Lond). 1992;6:305-7. 9. Chandran S. Ocular hazards of playing badminton. Br J Ophthalmol. 1974;58:757-60. 10. Zamora KV, Uy HS. Multicenter survey of badminton-related eye injuries. Phillip J Ophthalmol. 2006;31:26-8. 11. Kelly SP. Serious eye injury in badminton players. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:746-7. 12. Goldstein MH, Wee D. Sports injuries: an ounce of prevention and a pound of cure. Eye Contact Lens. 2011;37:160-3. 13. Eime R, McCarty C, Finch CF, Owen N. Unprotected eyes in squash: not seeing risk of injury. J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8:92-100. 14. McLean CP, DiLillo D, Bornstein BH, Bevins RA. Predictors of goggle use among racquetball players. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2008;15:167-70. 15. Nadolny M. Shuttlecocks and balls: the fastest moving objects in sport. Official Canadian Olympic Team Website. 2014 (updated 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 2014 September 11; cited 2015 March 22). ⟨http://olympic.ca/ 2014/09/11/shuttlecock-and-balls-the-fastest-moving-objects-in-sport⟩. Vinger PF The mechanisms and prevention of sports eye injuries. 2010 (cited 2015 March 22). ⟨www.lexeye.com/site/eye-safety.htm⟩. Pashby TJ. Eye injuries in Canadian amateur hockey. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7:254-7. Pashby T. Eye injuries in Canadian amateur hockey. Can J Opthalmol. 1985;20:2-4. Stuart MJ, Smith AM, Malo-Ortiquera SA, Fischer TL, Larson DR. A comparison of facial protection and the incidence of head, neck and facial injuries in Junior A hockey players. A function of individual playing time. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:39-44. Deady B, Brison RJ, Chevrier L. Head, face and neck injuries in hockey: A descriptive analysis. J Emerg Med. 1996;14:645-9. Can J Ophthalmol 2017;52:e143–e146 0008-4182/17/$-see front matter & 2017 Canadian Ophthalmological Society. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.01.018 pressure gradient secondary to choroidal expansion7 or ciliary block.4 Aqueous misdirection is typically managed by a combination of pharmacotherapy and laser capsulotomy. However, when refractory to medical and laser therapy, surgical removal of the anterior hyaloid, iris, and zonules (iridozonulohyaloidectomy) with vitrectomy may effectively create a permanent channel for aqueous flow.8 Here, we report aqueous misdirection cases with large myopic shifts and shallowing chambers in the presence of normal IOPs with or without glaucoma therapy after cataract surgery and highlight the laser and surgical approach for definitive treatment. Aqueous misdirection masked as myopia after cataract surgery Aqueous misdirection, reported by von Graefe in 1869, describes an uncommon finding occurring in up to 6% of cases after incisional ocular surgeries.1,2 It is characterized by a shallow peripheral and central anterior chamber depth (ACD), forward displacement of the lens–iris– diaphragm, and normal-to-elevated intraocular pressures (IOPs) in the absence of pupillary block or suprachoroidal hemorrhage.3 An abnormal anatomic relationship between ciliary processes, lens, and anterior hyaloid accumulates aqueous posterior to the ciliary body and anterior hyaloid causing anterior displacement of the lens–iris–diaphragm, resulting in narrow angles and a myopic shift in vision.4 Resistance across anterior hyaloid prevents forward flow of aqueous raising IOP.5 Ultrasound biomicroscopy studies in these patients support this phenomenon by showing anterior rotation of ciliary processes along with the ciliary body and forward displacement of the lens and iris.6 Other possible mechanisms include the development of a MATERIALS AND METHODS This retrospective case study reviewed the medical charts of 3 female patients and 1 male patient (7 eyes) aged 37–79 years (Tables 1 and 2). All patients were assessed at Rockyview General Hospital and affiliated clinics. The study was carried out following the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines (REB13-1132). Table 1—Patient demographics Case Age, y Sex Ocular History Time between Right and Left Eye Cataract Surgeries (mo) Onset of Aqueous Misdirection in the Fellow Eye Peripheral Iridotomy Before Surgical IZH Complete Vitrectomy and Anterior Hyaloidectomy 1 2 53 80 F M Unremarkable Angle-closure glaucoma 8 14 1 week 2 weeks Yes Yes Yes (OS only) Yes 3 37 F Angle-closure glaucoma Bilateral surgeries (same day) 1–2 weeks Yes Yes 4 73 F Angle-closure glaucoma N/A (OD only) N/A Yes Yes Aqueous misdirection occurred in the first eye within 1 month after cataract surgery. IZH, iridozonulohyaloidectomy. e146 CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. 52, NO. 4, AUGUST 2017 Complications N/A Four months after vitrectomy in the right eye, regrowth of an anterior capsular membrane was treated with laser peripheral capsulotomy through a prior iridotomy to restore ACD. During IZH, intraoperative complications in right eye led to inadvertent larger iridotomy/sphincterotomy with sector iridectomy superiorly that was immediately corrected with sutured iris. N/A