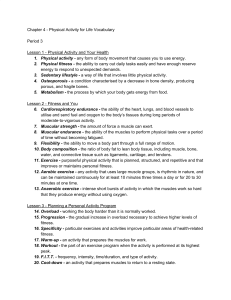

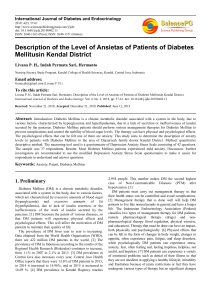

DINING FOR SAFETY: CONSUMER PERCEPTIONS OF FOOD SAFETY AND EATING OUT Andrew J. Knight Michigan State University Michelle R. Worosz Auburn University Ewen C. D. Todd Michigan State University This study investigates whether perceptions about food safety are related to how often consumers eat at restaurants. More specifically, it examines how the following affect the frequency of eating at restaurants: (a) concern about food safety issues, (b) food safety performance of restaurants, (c) how often consumers think about food safety, (d) the belief of having had food poisoning, (e) knowledge about food safety, and (f) sociodemographic variables. Using data from a nationwide telephone survey conducted with 1,014 randomly selected U.S. adults, the results indicated that perceptions of food safety do influence how often consumers eat at restaurants. Concern about food safety issues, thinking about food safety, and having experienced food poisoning were related to frequency of dining out. When comparing those who eat at restaurants rarely, occasionally, and often, most of the significant differences were between those who eat at restaurants rarely and those who dine out occasionally or often. KEYWORDS: consumer behavior; dining out; food safety; foodservice; restaurant; risk perception Despite food safety inspections at restaurants by public health officials, research has shown that a significant percentage of restaurants have inadequate food safety practices (Allwood, Jenkins, Paulus, Johnson, & Hedberg, 2004; Buchholz, Run, Kool, Fielding, & Mascola, 2002; Mathias et al., 1994; Medus, Smith, Bender, Besser, & Hedberg, 2006; U.S. Food and Drug Administration Retail Program Steering Committee, 2000; Walczak, 2000). In addition, restaurants have been implicated as a major source of food-borne illness outbreaks, which have been linked to a variety of food-borne pathogens and viruses (Buchholz et al., 2002; Cochran-Yantis et al., 1996; Cotterchio, Gunn, Coffill, Tormey, & Barry, 1998; Green et al., 2005; Lewis & Salsbury, 2001; Medus et al., 2006; Rudder, 2006; Wheeler et al., 2005). Food safety outbreaks can be costly for restaurants in terms of negative publicity, loss of consumer trust, and loss of Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, Vol. 33, No. 4, November 2009, 471-486 DOI: 10.1177/1096348009344211 © 2009 International Council on Hotel, Restaurant and Institutional Education 471 472 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH customers as well as public health compliance and legal costs (Grover & Dausch, 2000). The estimated cost for a restaurant associated with a food-borne illness outbreak is at least $100,000, which includes lost business and wages and medical and lawyer fees (Grover & Dausch, 2000). Additionally, a restaurant can expect to suffer a 30% reduction in sales following a food-borne illness outbreak (Grover & Dausch, 2000). Considering the risk of food-borne illness and the importance of food safety at restaurants, it is surprising that few studies have examined the relationship between consumer perceptions of food safety and dining at restaurants. In this study, we systematically investigate whether perceptions of food safety affect how often consumers eat at restaurants. BACKGROUND The importance of food safety in the foodservice industry is highlighted by research showing that most cases of food-borne disease outbreaks have been linked to the mishandling of food in foodservice institutions or in homes (Greig, Todd, Bartleson, & Michaels, 2007; Redmond & Griffith, 2005; Williamson, Gravani, & Lawless, 1992). In addition, trends have shown that meals purchased away from the home have increased (Buchholz et al., 2002; Carlson, Kinsey, & Nadav, 2002), with the restaurant industry accounting for a 47.5% share of the food dollar in 2006 (National Restaurant Association, 2006). This section reviews previous studies that have examined consumer perceptions of food safety and how consumer perceptions of food safety have influenced behavior. Consumer Perceptions of Food Safety at Restaurants Williamson et al. (1992) found that 33% of respondents indicated that food safety problems were most likely the result of unsafe practices at restaurants. Of the 372 respondents in a U.S. national telephone survey conducted in 1993 who reported that they or someone in their household had contracted a food-borne illness in the past month, 65% of them believed restaurants were the cause of their illness (Fein, Lin, & Levy, 1995). Green et al. (2005), in a 2002 telephone survey of 16,435 randomly selected U.S. adults, asked respondents about their beliefs concerning sources of gastrointestinal illness. Of those who experienced vomiting or diarrhea in the month before being interviewed, 22% believed their illness was related to eating a meal outside of the home. This belief varied by age, education, experience of illness, and frequency of eating out. Specifically, respondents who were younger than 33 years, had some college education, reported having diarrhea but no vomiting, reported not missing work, and had eaten out in the previous week were significantly more likely to believe that their illness was because of an outside meal. Consumers who believed they became ill after eating at a restaurant associated the illness with the timing of the illness, the appearance and taste of the meal, the property of the meal (e.g., spicy, greasy), dining companions also becoming ill, eating foods that they do not usually eat, and the cleanliness of the restaurant, kitchen, and food workers. Green et al. (2005) also found that only 8% of ill respondents, who believed that Knight et al. / DINING FOR SAFETY 473 they contracted their illness from a meal outside of the home, notified the suspected foodservice facility or health department. Using data from a 2003 mail survey conducted in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, Henson et al. (2006) stated that 39% of 321 respondents reported having been ill after eating at a restaurant. Of those, only 17% had consulted their family practitioner, and only 7% had reported their illness to a public health official. Henson et al. (2006) discovered that four factors were related to consumer perceptions of food safety at restaurants. These factors were observed standard of hygiene (e.g., cleanliness), overall quality of the restaurant (e.g., price, quality of food, appearance and/or attitude of staff), level of patronage (e.g., number of people eating in the restaurant, length of time restaurant has been open), and external information (e.g., reviews, friends/family, inspection notice in window). Of these four factors, cleanliness explained the most variance followed by overall quality, level of patronage, and external information. Consumer Perceptions of Food Safety As evidenced above, few studies have examined consumer perceptions of food safety at restaurants; however, there is a rather substantial literature on perceptions of food safety. Most of these studies have examined perceptions of microbial and technological food risks, including pesticide residues, additives, preservatives, antibiotics, and hormones. Variables such as knowledge, trust, and sociodemographics have been associated with level of concern about food safety. Knowledge refers to the level of information a person possesses about a particular risk. Generally, it is hypothesized that perception of food safety risks decrease with increasing levels of knowledge (Frewer, Shepherd, & Sparks, 1994; Groothuis & Miller, 1997; Jordan & Elnagheeb, 1991; Knight & Warland, 2005). It can also be hypothesized that the type of experience influences risk perception (Knight & Warland, 2005). For instance, if people believe that they became ill because of foods consumed at restaurants, they might dine at restaurants less frequently. The logic behind trust is that people who have higher levels of trust in institutions and systems, such as the food system, will be less concerned with risks and vice versa (Knight & Warland, 2005). A person, for example, who believes that restaurants are capable and perform their roles effectively will have lower concerns about food safety. Gender, race, presence of children, age, education, and income were identified as common sociodemographic variables included in food safety studies (Brewer & Prestat, 2002; Flynn, Slovic, & Mertz, 1994; Hwang, Roe, & Teisl, 2005; Jordan & Elnagheeb, 1991; Knight & Warland, 2005; Lin, 1995; Nayga, 1996; Rimal, Fletcher, McWatters, Misra, & Deodhar, 2001; Rohr, Luddecke, Muller, & Alvensleben, 2005). The significance of sociodemographic variables varies by the food safety risk and from study to study. Food Safety Perceptions and Behavior There are only two known studies on food safety perceptions and consumer behavior at restaurants. The first, by Reynolds and Balinbin (2003), examined 474 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH the impacts of mad cow disease on in-restaurant behavior in London, United Kingdom. Reynolds and Balinbin (2003) surveyed 288 restaurant managers about overall and beef sales in the years following the mad cow disease scare. The findings in their study were consistent with the broader food safety literature in that food outbreaks and scares can affect consumer purchasing behavior (Bocker & Hanf, 2000; Herrmann, Sterngold, & Warland, 1998; Mueller, 1990), which usually results in a pattern of a sharp and immediate decline in sales of the foods associated with the outbreak followed by a slow and often incomplete recovery toward previous consumption levels (Bocker & Hanf, 2000). Although Reynolds & Balinbin (2003) found that beef sales declined in the years following the mad cow disease scare, overall restaurant sales increased, particularly for restaurants featuring nonbeef items. The second published study on food safety perceptions and consumer behavior at restaurants by Henson et al. (2006) investigated how consumers perceived food safety at restaurants and how these judgments affected restaurant choice. They found that 56% of respondents had stopped eating at a restaurant they had previously frequented because of food safety concerns; in addition, 48% said that they had chosen not to eat at a restaurant because of food safety concerns. Fast food and ethnic restaurants were most often mentioned as restaurant types for which respondents had particular food safety concerns. In the case of foods, prior research shows that food safety concerns, particularly concern about pesticides and chemicals, do affect purchase intention or consumption, at least for some consumers (Byrne, Bacon, & Toensmeyer, 1994; Collins, Cuperus, Cartwright, Stark, & Ebro, 1992; Estes & Smith, 1996; Norris, Cuperus, & Collins, 1991; Rimal et al., 2001; Schafer, Schafer, Bultena, & Hoiberg, 1993; Wessells, Kline, & Anderson, 1996). Similarly, willingness-to-pay studies suggest that consumers are willing to pay more for products that are perceived to be safer or to be of lower risk (Baker & Crosbie, 1994; Eom, 1994; Huang, 1993; Latouche, Rainelli, & Vermersch, 1998; Rohr et al., 2005; Roosen, Fox, Hennessy, & Schreiber, 1998; Yeung & Morris, 2001). However, Rimal et al. (2001) claim that there is a gap between level of concern about food safety and food consumption habits, and this gap is related to education; the gap decreases with higher education levels. Knowledge about food safety and trust in the food system also influenced whether consumers altered their food purchasing habits. Respondents with higher levels of knowledge of food safety and those with lower levels of trust in the food system were less likely to alter their food purchase patterns (Rimal et al., 2001). Hypotheses Based on the review of previous literature on perceptions of food safety and consumer behavior, we will test two overarching hypotheses in this study. Hypothesis 1: Whether perceptions about food safety issues are related to the frequency of eating at restaurants, which can be stated in five subhypotheses: Hypothesis 1a: Respondents who are more concerned about food safety will eat at restaurants less frequently than those who are less concerned about food safety. Knight et al. / DINING FOR SAFETY 475 Hypothesis 1b: Respondents who have higher levels of trust in restaurants will eat at restaurants more frequently than those with lower levels of trust. Hypothesis 1c: Respondents who think about food safety more often will eat at restaurants less frequently than those who think about food safety less often. Hypothesis 1d: Respondents who believe that they have had food poisoning will eat at restaurants less frequently than those who do not believe that they have had food poisoning. Hypothesis 1e: Respondents with higher levels of knowledge about food safety will eat at restaurants more frequently than those with lower levels of knowledge. Hypothesis 2: Whether the sociodemographic characteristics of consumers are related to frequency of eating at restaurants. Following the food safety literature, we expect that vegetarians and vegans, the presence of someone with food allergies, someone with a child younger than 6 years and/or an elderly person in their household, older respondents, those with lower levels of education, and those with lower incomes will be less likely to eat at restaurants. METHOD The data for this study were gathered in a nationwide telephone survey in the 48 contiguous U.S. states and conducted with 1,014 randomly selected U.S. adults aged 18 and older between October 31, 2005, and February 9, 2006. Because of the damage sustained by Hurricane Katrina, affected counties in the Gulf of Mexico, including the city of New Orleans, were omitted from the sample design. To insure the inclusion of both listed and unlisted telephone numbers, randomdigit dialing procedures were used. Two calling protocols were used. For the first protocol, the traditional standard of a minimum of 12 call attempts to contact sample members was employed or until a final disposition was determined; similar to the traditional protocol, cases in the second protocol were randomly assigned to be called at different times of the day and days of the week, but each case received only a single call attempt. The cooperation rate for the traditional protocol was 42% and 67% for the one-call protocol for a total cooperation rate of 52%. The use of two protocol procedures did not significantly affect either the composition of respondents or the responses of respondents. Results were weighted to reflect the sociodemographics (age, sex, race, and education) and geographic regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and the West) of the U.S. population using the 2000 census data. Ideally, ordinal regression would be the preferred statistical technique to preserve the ordinal nature of the dependent variable. However, the assumption that the relationships between the independent variables and the logits are the same for all the logits (parallel lines) was violated (p ≤ 001), so a decision was made to treat the dependent variable as categorical or nominal data. Multinomial logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationships between perceptions of food safety, sociodemographics, and frequency of eating at a restaurant. 476 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Dependent Variable The dependent variable, frequency of eating at a restaurant, was measured by asking respondents “About how many times a week do you eat at a restaurant?” Response categories were 1 = everyday, 2 = several times a day or a week, 3 = about once or twice a week, 4 = less than once a week, and 5 = never. To aid in the interpretation of the data analysis, the dependent variable was recoded into three categories, where 1 = frequently (by adding together “everyday” and “several times a day or a week” responses), 2 = occasionally (about once or twice a week), and 3 = rarely (by adding together the “less than once a week” and “never” categories). Independent Variables Six food safety variables were included in the analysis. First, concern about food-borne illness was measured by combining two questions. Respondents were asked, “Are you concerned about food-borne illnesses, such as Salmonella, E. coli, or Listeria, in the foods you eat?” If respondents answered “yes,” they were asked the follow-up question: “And would you say that you are very concerned, somewhat concerned, or a little concerned?” The responses to these two questions were recoded into one variable, where 1 = very concerned, 2 = somewhat concerned, 3 = a little concerned, and 4 = no, they were not concerned. Second, the same procedures were followed for concern about additives and preservatives. Respondents were also asked to rate their level of concern with two other food safety issues: (a) pesticide and chemical residues on fruits and vegetables and (b) antibiotics and hormones. These two variables were moderately correlated with each other, and they were correlated with concern about food-borne illnesses and additives and preservatives. Additionally, they were not significantly related to the frequency of eating at restaurants, so these two variables, concern about pesticides and chemicals and concern about antibiotics and hormones, were removed from the final models presented in this article. The third variable trust was measured by asking respondents: “How would you rate the performance of restaurants in making sure the foods you eat are safe?” where the response categories were 1 = a very good job, 2 = a good job, 3 = neither a good nor poor job, 4 = a poor job, and 5 = a very poor job. Fourth, to gauge how important food safety was to respondents, they were asked, “Would you say you think about food safety?” The response categories were 1 = everyday, 2 = several times a week, 3 = once in a while, 4 = hardly at all, or 5 = never. Because of the ordinal nature of this variable, it was treated as categorical in the analysis with “everyday” being the reference category. Fifth, experience was assessed by asking respondents whether they thought that they had had a case of food poisoning within the past year (“no” was the reference category). Sixth, perceived knowledge was measured by asking respondents to rate their knowledge about food safety, where 1 = a lot, 2 = quite a bit, 3 = a little, and 4 = not much at all. Nine sociodemographic control variables were included in the models: whether the respondent was a vegetarian or vegan, whether anyone living in Knight et al. / DINING FOR SAFETY 477 their household was allergic to foods, whether there were any children younger than 6 in the household, and whether there was anyone 65 years or older in the household. For all these variables, the response categories were “yes” or “no,” with “no” serving as the reference category. In addition, age was measured by interval by asking respondents “In what year were you born?” The year provided by the respondent was then subtracted from 2005 or 2006, depending on the calendar year of the interview. The interviewers recorded the sex of the respondent with females acting as the reference category. Race was measured by asking respondents to describe their race or ethnicity with Caucasian/White serving as the reference category and the other categories being African American/Black, Hispanic, and Other. Education was measured by asking respondents: “What is the highest level of education you have completed?” Education was then recoded into four categories (less than high school, high school, some college/technical diploma, and bachelor’s degree or higher) to best conceptualize the various educational categories and to be consistent with previous studies. The reference category was bachelor’s degree or higher. Income was measured by initially asking respondents whether their total annual household income in 2004 was $30,000 or more. Depending on their answer, they were then asked whether their total annual income was more or less than another threshold number. This threshold technique was used to increase responses to a sensitive issue such as income. The eight income thresholds ranged from “less than $10,000” to “$70,000 or more.” For the purposes of this analysis, income was recoded into four categories (less than $20,000, $20,000-$39,999, $40,000-$59,999, and $60,000 or more), with the reference category being “$60,000 or more.” Descriptive statistics for the independent variables are presented in Table 1. RESULTS About 18% of respondents stated that they eat at a restaurant often (“everyday” or “several times a day or a week”); 43% indicated that they dine out occasionally (about once or twice a week); and 39% said that they rarely eat out (“less than once a week” or “never”). The multinominal logistic regression results are presented in Table 2. Three multinominal regression models are shown in this table. The first model examines differences between eating at restaurants occasionally and often; differences between eating at restaurants rarely and often are portrayed in the second model. Differences between eating at restaurants rarely and occasionally are illustrated in the third model. For Model 1, “occasionally” serves as the reference category. In both Models 2 and 3, “rarely” is the reference category. The results in Model 1 show that there were few significant differences bet­ ween those who eat at restaurants occasionally and often. The only food safety variable that was statistically significant was thinking about food safety, where respondents who think about food safety hardly at all were more likely to eat at a restaurant more often than those who think about food safety everyday. Males 478 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Table 1 Descriptive Statistics for Independent Variables (N = 787) Mean/ Percentage Standard Deviation Food safety variables 1. Concern about food-borne illness 2.183 1.134 2. Concern about additives and preservatives 2.662 1.224 3. Performance of restaurants 2.460 0.932 4. Think about food safety (Everyday [reference]) 33.2% a. Several times a week 14.8% 0.355 b. Once in a while 37.2% 0.484 c. Hardly at all 12.6% 0.332 d. Never 2.2% 0.145 5. Had food poisoning (No [reference]) 92.0% a. Yes 8.0% 0.268 6. Knowledge 2.350 0.883 Sociodemographics 7. Vegetarian or vegan (No [reference]) 88.0% a. Yes 12.0% 0.327 8. Allergic present (No [reference]) 73.0% a. Yes 27.0% 0.444 9. Child present (No [reference]) 75.0% a. Yes 25.0% 0.435 10. Elderly present (No [reference]) 79.0% a. Yes 21.0% 0.407 11. Age 43.196 16.702 12. Sex (female [reference]) 53.0% a. Male 47.0% 0.500 13. Education (Bachelor’s degree [reference]) 26.7% a. Less than high school 4.9% 0.216 b. High school 37.8% 0.485 c. Some college/technical diploma 30.6% 0.461 14. Race (White [reference]) 74.0% a. African American 10.5% 0.307 b. Hispanic 11.6% 0.320 c. Other 3.9% 0.194 15. Income ($60,000 or more [reference]) 37.6% a. Less than $20,000 13.7% 0.344 b. $20,000-$39,999 22.5% 0.418 c. $40,000-$59,999 26.2% 0.440 Range 1-4 1-4 1-5 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 1-4 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 18-96 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 0-1 were more likely than females to eat at a restaurant often, and Hispanics were less likely than White respondents to eat at a restaurant often. The findings, however, change in Model 2, which looks at differences between eating at restaurants rarely and often. Four food safety variables—concern about food-borne illness, concern about additives and preservatives, thinking about food safety, and whether the respondent believed he or she had food poisoning—were related to frequency of eating at restaurants. The likelihood of eating at a restaurant often decreased with level of concern about food-borne 479 B Exp(B) B Exp(B) Model 2 (Often); Rarely (Reference) B (continued) 0.290 0.888 0.692 0.354 0.826 0.970 1.003 0.986 2.167 2.789 0.916 1.837 0.523 4.087 1.192 0.665 1.365 0.984 Exp(B) Model 3 (Occasionally); Rarely (Reference) Food safety variables: 1. Concern about food-borne illness 0.101 (0.122) 1.106 −0.306* (0.130) 0.736 −0.408*** (0.101) 2. Concern about additives and preserva®tives −0.034 (0.107) 0.967 0.278* (.115 ) 1.320 0.311*** (0.086) 3. Performance of restaurants −0.043 (0.124) 0.958 −0.060 (0.134) 0.942 −0.017 (0.105) 4. Think about food safety (Everyday [reference]) a. Several times a week 0.441 (0.356) 1.554 1 .466*** (0.398) 4.333 1.026*** (0.311) b. Once in a while 0.240 (0.434) 1.271 0.152 (0.357) 1.164 −0.088 (0.255) c. Hardly at all 0.822* (0.401) 2.275 1.430*** (0.438) 4.180 0.608 (.357) d. Never 0.918 (0.982) 2.504 0.270 (0.869) 1.309 −0.648 (0.738) 5. Had food poisoning 0.536 (0.377) 1.710 1.944*** (0.492) 6.988 1.408*** (0.430) 6. Knowledge −0.229 (0.137) 0.795 −0.054 (0.146) 0.948 0.175 (0.114) Sociodemographics 7. Vegetarian or vegan 0.136 (0.410) 1.146 −0.903* (0.404) 0.405 −1.039*** (0.300) 8. Allergy present 0.038 (0.296) 1.038 −0.154 (0.305) 0.858 −0.191 (0.226) 9. Child present 0.058 (0.290) 1.059 0.027 (0.313) 1.027 −0.031 (0.237) 10. Elderly present −0.159 (0.355) 0.853 −0.156 (0.369) 0.855 0.003 (0.270) 11. Age −0.001 (0.009) 0.999 −0.016 (0.010) 0.984 −0.014 (0.008) 12. Sex (female [reference]) 0.672** (0.238) 1.958 1.445*** (0.251) 4.244 0.774*** (0.187) 13. Education (bachelor’s degree [reference]) a. Less than high school 0.290 (0.769) 1.337 −0.948 (0.731) 0.387 −1.238* (0.586) b. High school 0.224 (0.299) 1.252 0.106 (0.324) 1.112 −.118 (0.245) c. Some college/technical diploma 0.173 (0.310) 1.189 −0.194 (0.329) 0.823 −.368 (0.246) Variable Model 1 (Often); Occasionally (Reference) Table 2 Results of the Multinomial Logistic Regression Model Estimation for Frequency of Eating at Restaurants (N = 787) 480 B Exp(B) B Exp(B) Model 2 (Often); Rarely (Reference) B Note: Standard errors in parentheses. *p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001. 0.567 0.591 0.938 0.874 13.823 0.744 Exp(B) Model 3 (Occasionally); Rarely (Reference) 14. Race (White [reference]) a. African American −0.223 (0.426) 0.800 −0.358 (0.437) 0.699 −0.135 (0.309) b. Hispanic −2.217*** (0.548) 0.109 0.410 (0.708) 1.506 2.626*** (0.503) c. Other 0.827 (0.514) 2.285 0.531 (0.536) 1.701 −.295 (0.499) 15. Income ($60,000 or more [reference]) a. Less than $20,000 0.811 (0.431) 2.250 0.244 (0.445) 1.276 −0.567 (0.370) b. $20,000-$39,999 −0.154 (0.332) 0.857 −0.680* (0.346) 0.507 −.526* (0.252) c. $40,000-$59,999 −0.011 (0.300) 0.989 −.076 (0.318) 0.927 −.064 (0.237) Constant 1.290 (0.776) −.947 (0.822) 0.343 (0.625) Cox and Snell R2 0.300 −2 log likelihood 1313.784*** Variable Model 1 (Often); Occasionally (Reference) Table 2 (continued) Knight et al. / DINING FOR SAFETY 481 illness and increased with level of concern about additives and preservatives. In other words, respondents with higher levels of concern about food-borne illness were less likely to eat at a restaurant often than those with higher levels of concern. Those with higher levels of concern about additives and preservatives were more likely to eat at a restaurant often than those with lower levels of concern. Additionally, respondents who think about food safety “several times a week” or “hardly at all” were more likely to eat at a restaurant often than those who think about food safety everyday. Food poisoning had the opposite effect than expected. Those who believed that they had food poisoning within the past year were more likely to eat at a restaurant often than those who did not believe that they had food poisoning. Three sociodemographic variables were significantly related to frequency of eating at restaurants. Vegetarians and vegans were less likely to eat at restaurants often. Males were more likely to eat at a restaurant often than females, and those with incomes between $20,000 and $39,999 were less likely to eat out often than those with incomes $60,000 or greater. Differences between eating at restaurants rarely and occasionally are presented in Model 3. The results are similar to those in Model 2 with a few exceptions. First, the significance levels (p values) are more pronounced for some of the variables such as concern about food-borne illness and concern about additives and preservatives. Second, two additional sociodemographic variables were significant. Respondents with less than a high school education were less likely to eat at a restaurant occasionally than those with at least a bachelor’s degree, and Hispanics were more likely to eat at a restaurant occasionally than Whites. DISCUSSION This article’s primary purpose was to investigate whether consumers’ perceptions of food safety influence the frequency of dining at restaurants. The findings show they do but not always in predictable ways. The most striking differences were between those who eat at restaurants rarely (less than once a week) and those who dine occasionally (once or twice a week) or often (at least several times a week). There were few significant differences between respondents who eat out occasionally and those who eat out often. As hypothesized, concern about food safety issues, thinking about food safety, and having experienced food poisoning were related to frequency of dining. However, the relationships between level of concern about additives and preservatives and having experienced food poisoning had the opposite effect than predicted; respondents who had higher levels of concern about additives and preservatives and those who believed that they had experienced food poisoning reported that they were likely to eat at restaurants. Considering that those who were more highly concerned about food-borne illness were more likely to eat at restaurants rarely, one would have expected the other food-borne illness measures to act in a similar fashion. Contrary to our expectations, only four sociodemographic variables were significantly related to eating at restaurants in at least two of the three models, 482 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH controlling for food safety variables. In all three models, males were more likely to eat at restaurants more often than females. Vegetarians or vegans were more likely to eat at restaurants rarely than meat eaters. Future research might examine why vegetarians or vegans reported eating at restaurants less frequently, especially when more restaurants are offering vegetarian dishes. Compared with White respondents, Hispanic respondents were more likely to eat occasionally at restaurants. Finally, respondents with incomes between $20,000 and $39,999 were more likely to eat rarely at restaurants than respondents with annual household incomes $60,000 or greater. An explanation for the unpredicted findings may lie in the wording of the questions. For example, the question about experiencing food poisoning did not specify whether the respondent believed that he or she became ill from eating at a restaurant. Thus, respondents may not have associated food poisoning with restaurants. Another explanation is that even if a respondent did associate his or her food poisoning with restaurants, it could be that consumers will only change their purchasing habits at that particular restaurant. The frequency of dining at restaurants in general might not change, but the pattern of patronage may change as consumers eat elsewhere (Henson et al., 2006; Reynolds & Balinbin, 2003). Both these explanations require further research. A final explanation is that food-borne illnesses may cause a short-term decline in eating out, but consumer patterns may return to previous levels over a period of time (Bocker & Hanf, 2000). In the case of concern about food additives and preservatives, it may be that consumers associate restaurants with serving fresh foods; thus, they may think that additives and preservatives are not used in foods served in restaurants. This hypothesis also requires further research. Surprisingly, the food safety performance of restaurants was not significantly related to frequency of eating at restaurants, which is contrary to the findings of previous research (Henson et al., 2006). Our performance variable may not be capturing the key aspects of food safety as outlined by Henson et al. (2006). In their study, cleanliness was the most often cited attribute used by consumers to determine food safety at restaurants; respondents in this study may have interpreted “performance” differently. Still, the findings reinforce the importance of establishing and enforcing food safety protocols at restaurants. To reassure customers, it may be beneficial for restaurants to publicize their food safety records and strategies such as employee training or Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) programs. Aside from the limitations of some measures, another limitation of this study was that distinctions were not made between fast-food and sit-down restaurants or other types of restaurants, for example, chains, independent, and ethnic. The findings in this study suggest that more research is needed in this area including how, when, and why consumers associate illness with food purchased at restaurants and how purchasing habits change with those associations. Furthermore, food safety variables need to be included in consumer preference studies. When a consumer makes a decision whether to patronize Knight et al. / DINING FOR SAFETY 483 a restaurant, it is likely that food safety is only one of several attributes considered; other attributes might include the appearance, nutrition, taste, convenience, brand, price of foods, previous experiences, and recommendations by others, as well as the restaurant’s atmosphere, entertainment value, location, and reputation (Auty, 1992; Gregory & Kim, 2004; Stewart, Blissard, & Jolliffe, 2006). Although this study provides a step in this direction, future research should expand on our research and that of Henson et al. (2006) to understand how consumers perceive food safety at restaurants and to investigate which food safety issues are most salient to them. In particular, there is a need to delineate the effects of food safety and other preferences on consumer behavior. REFERENCES Allwood, P. B., Jenkins, T., Paulus, C., Johnson, L., & Hedberg, C. W. (2004). Hand washing compliance among retail food establishment workers in Minnesota. Journal of Food Protection, 67, 2825-2828. Auty, S. (1992). Consumer choice and segmentation in the restaurant industry. The Service Industries Journal, 12, 324-339. Baker, G. A., & Crosbie, P. J. (1994). Consumer preferences for food safety attributes: A market segment approach. Agribusiness, 10, 319-324. Bocker, A., & Hanf, C.-H. (2000). Confidence lost and—partially—regained: Consumer response to food scares. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 43, 471485. Brewer, M. S., & Prestat, C. J. (2002). Consumer attitudes toward food safety issues. Journal of Food Safety, 22, 67-83. Buchholz, U., Run, G., Kool, J. L., Fielding, J., & Mascola, L. (2002). A risk-based restaurant inspection system in Los Angles County. Journal of Food Protection, 65, 367-372. Byrne, P. J., Bacon, J. R., & Toensmeyer, U. C. (1994). Pesticide residue concerns and shopping location likelihood. Agribusiness, 10, 491-501. Carlson, A., Kinsey, J., & Nadav, C. (2002). Consumers’ retail source of food: A cluster analysis. Family Economics and Nutrition Review, 14, 11-20. Cochran-Yantis, D., Belo, P., Giampaoli, M. S., McProud, L., Rehs, V. E., & Rehs, J. G. (1996). Attitudes and knowledge of food safety among Santa Clara County, California restaurant operators. Journal of Foodservice Systems, 9, 117-128. Collins, J. K., Cuperus, G. W., Cartwright, B., Stark, J. A., & Ebro, L. L. (1992). Consumer attitudes on pesticide treatment histories of fresh produce. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 3, 81-98. Cotterchio, M., Gunn, J., Coffill, T., Tormey, P., & Barry, M. A. (1998). Effect of a manager training program on sanitary conditions in restaurants. Public Health Reports, 113, 353-358. Eom, Y. S. (1994). Pesticide residue risk and food safety valuation: A random utility approach. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 76, 760-771. Estes, E. A., & Smith, V. K. (1996). Price, quality, and pesticide related health risk considerations in fruit and vegetable purchases: A hedonic analysis of Tucson, Arizona supermarkets. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 27, 59-76. 484 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Fein, S. B., Lin, C. T. J., & Levy, A. S. (1995). Foodborne illness: Perceptions, experience, and preventive behaviors in the United States. Journal of Food Protection, 58, 1405-1411. Flynn, J., Slovic, P., & Mertz, C. K. (1994). Gender, race, and perception of environmental health risks. Risk Analysis, 14, 1101-1108. Frewer, L. J., Shepherd, R., & Sparks, P. (1994). The interrelationship between perceived knowledge, control and risk associated with a range of food-related hazards targeted at the individual, other people and society. Journal of Food Safety, 14, 19-40. Green, L. R., Selman, C., Scallan, E., Jones, T. F., Marcus, R., & EHS-NET Population Survey Working Group. (2005). Beliefs about meals eaten outside the home as sources of gastrointestinal illness. Journal of Food Protection, 68, 2184-2189. Gregory, S., & Kim, J. (2004). Restaurant choice: The role of information. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 7, 81-95. Greig, J., Todd, E. C. D., Bartleson, C., & Michaels, B. (2007). Outbreaks where food workers have been implicated in the spread of foodborne disease: Part 1: Description of the problem, methods and agents involved. Journal of Food Protection, 70, 1752-1761. Groothuis, P. A., & Miller, G. (1997). The role of social distrust in risk-benefit analysis: A study of the siting of a hazardous waste disposal facility. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 15, 241-257. Grover, S. F., & Dausch, J. G. (2000). Hepatitis A in the foodservice industry. Food Management, 35, 80-86. Henson, S., Majowicz, S., Masakure, O., Sockett, P., Jones, A., Hart, R., et al. (2006). Consumer assessment of the safety of restaurants: The role of inspection notices and other information cues. Journal of Food Safety, 26, 275-301. Herrmann, R. O., Sterngold, A., & Warland, R. H. (1998). Comparing alternative question forms for assessing consumer concerns. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 32, 13-29. Huang, C. L. (1993). Simultaneous-equation model for estimating consumer risk perceptions, attitudes, and willingness-to-pay for residue-free produce. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 27, 377-396. Hwang, Y.-J., Roe, B., & Teisl, M. F. (2005). An empirical analysis of United States consumers’ concerns about eight food production and processing technologies. AgBioForum, 8(1). Jordan, J. L., & Elnagheeb, A. H. (1991). Public perceptions of food safety. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 22, 13-22. Knight, A. J., & Warland, R. (2005). Determinants of food safety risks: A multi-disciplinary approach. Rural Sociology, 70, 253-275. Latouche, K., Rainelli, P., & Vermersch, D. (1998). Food safety issues and the BSE scare: Some lessons from the French case. Food Policy, 23, 347-356. Lewis, G., & Salsbury, P. A. (2001). Safe food at retail establishments. Food Safety Magazine, 7, 13-17. Lin, C. T. J. (1995). Demographic and socioeconomic influences on the importance of food safety in food shopping. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 24, 190-198. Mathias, R. G., Riben, P. D., Campbell, E., Wiens, M., Cocksedge, W., Hazlewood, A., et al. (1994). The evaluation of the effectiveness of routine restaurant inspections and education of food handlers: restaurant inspection survey. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 85(Suppl. 1), S61-S66. Knight et al. / DINING FOR SAFETY 485 Medus, C., Smith, K. E., Bender, J. B., Besser, J. M., & Hedberg, C. W. (2006). Salmonella outbreaks in restaurants in Minnesota, 1995 through 2003: Evaluation of the role of infected foodworkers. Journal of Food Protection, 69, 1870-1878. Mueller, W. (1990). Who’s afraid of food? (Consumer boycotts due to fears over adulterated food). American Demographics, 12, 40-43. National Restaurant Association. (2006). 2006 restaurant industry fact sheet. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://www.restaurant.org/research/ Nayga, R. M., Jr. (1996). Sociodemographic influences on consumer concern for food safety: The case of irradiation, antibiotics, hormones, and pesticides. Review of Agricultural Economics, 18, 467-475. Norris, P. E., Cuperus, G. W., & Collins, J. K. (1991). Appearance, cost and pesticide residue impacts on produce purchases. Current Farm Economics, 64, 13-22. Redmond, E. C., & Griffith, C. J. (2005). Consumer perceptions of food safety education sources: Implications for effective strategy development. British Food Journal, 107, 467-483. Reynolds, D., & Balinbin, W. M. (2003). Mad cow disease: An empirical investigation of restaurant strategies and consumer response. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 27, 358-368. Rimal, A., Fletcher, S. M., McWatters, K. H., Misra, S. K., & Deodhar, S. (2001). Perception of food safety and changes in food consumption habits: A consumer analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 25, 43-52. Rohr, A., Luddecke, K., Muller, M. J., & Alvensleben, R. V. (2005). Food quality and safety—Consumer perception and public health concern. Food Control, 16, 649-655. Roosen, J., Fox, J. A., Hennessy, D. A., & Schreiber, A. (1998). Consumers’ valuation of insecticide use restrictions: An application to apples. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 23, 367-384. Rudder, A. (2006). Food safety and the risk assessment of ethnic minority food retail business. Food Control, 17, 189-196. Schafer, E., Schafer, R. B., Bultena, G. L., & Hoiberg, E. O. (1993). Safety of the U.S. food supply: Consumer concerns and behaviour. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics, 17, 137-144. Stewart, H., Blissard, N., & Jolliffe, D. (2006). Let’s eat out: Americans weigh taste, convenience, and nutrition. Retrieved July 16, 2009, from http://www.ers.usda.gov/ publications/eib19/eib19.pdf U.S. Food and Drug Administration Retail Program Steering Committee. (2000). Report of the FDA retail food program database of foodborne illness risk factors. Silver Spring, MD: Author. Walczak, D. (2000). Overcoming barriers to restaurant food safety. FIU Hospitality Review, 18, 89-97. Wessells, C. R., Kline, J., & Anderson, J. G. (1996). Seafood safety perceptions and their effects on anticipated consumption under varying information treatments. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 25(1), 12-21. Wheeler, C., Vogt, T. M., Armstrong, G. L., Vaughan, G., Weltman, A., Nainan, O. V., et al. (2005). An outbreak of Hepatitis A associated with green onions. New England Journal of Medicine, 353, 890-897. Williamson, D. M., Gravani, R. B., & Lawless, H. T. (1992). Correlating food safety knowledge with home food-preparation practices. Food Technology, 46, 94-100. Yeung, R. M. W., & Morris, J. (2001). Food safety risk: Consumer perception and purchase behaviour. British Food Journal, 103, 170-186. 486 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Submitted January 12, 2007 First Revision Submitted April 27, 2007 Final Revision Submitted December 6, 2007 Accepted May 20, 2008 Refereed Anonymously Andrew J. Knight, PhD (e-mail: [email protected]) is a Senior Planing and Development Officer in the Industry Development & Business Services branch of the Nova Scotia Department of Agriculture. Michelle R. Worosz, PhD (e-mail: michelle_worosz@auburn. edu), is an assistant professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology at Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama. Ewen C. D. Todd (e-mail: todde@ msu.edu) is a Professor in the Department of Advertising, Public Relations & Retailing at Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan.