Uploaded by

common.user18193

Deception by Implication: Typology of Truthful Misleading Ads

advertisement

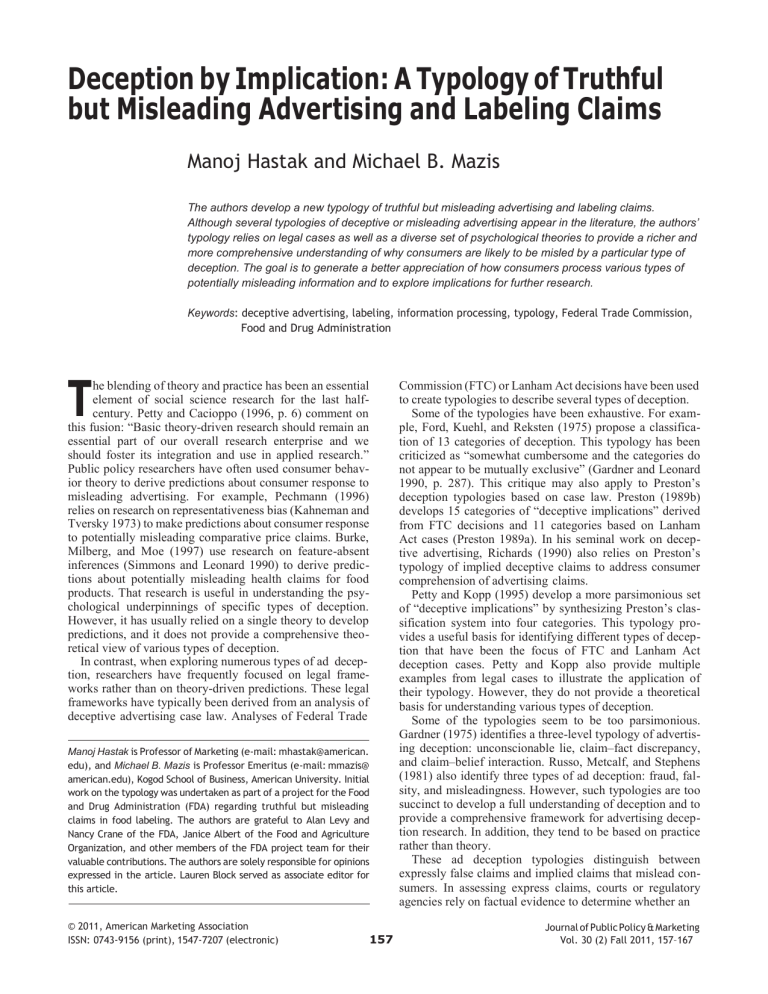

Deception by Implication: A Typology of Truthful but Misleading Advertising and Labeling Claims Manoj Hastak and Michael B. Mazis The authors develop a new typology of truthful but misleading advertising and labeling claims. Although several typologies of deceptive or misleading advertising appear in the literature, the authors’ typology relies on legal cases as well as a diverse set of psychological theories to provide a richer and more comprehensive understanding of why consumers are likely to be misled by a particular type of deception. The goal is to generate a better appreciation of how consumers process various types of potentially misleading information and to explore implications for further research. Keywords: deceptive advertising, labeling, information processing, typology, Federal Trade Commission, Food and Drug Administration T he blending of theory and practice has been an essential element of social science research for the last halfcentury. Petty and Cacioppo (1996, p. 6) comment on this fusion: “Basic theory-driven research should remain an essential part of our overall research enterprise and we should foster its integration and use in applied research.” Public policy researchers have often used consumer behavior theory to derive predictions about consumer response to misleading advertising. For example, Pechmann (1996) relies on research on representativeness bias (Kahneman and Tversky 1973) to make predictions about consumer response to potentially misleading comparative price claims. Burke, Milberg, and Moe (1997) use research on feature-absent inferences (Simmons and Leonard 1990) to derive predictions about potentially misleading health claims for food products. That research is useful in understanding the psychological underpinnings of specific types of deception. However, it has usually relied on a single theory to develop predictions, and it does not provide a comprehensive theoretical view of various types of deception. In contrast, when exploring numerous types of ad deception, researchers have frequently focused on legal frameworks rather than on theory-driven predictions. These legal frameworks have typically been derived from an analysis of deceptive advertising case law. Analyses of Federal Trade Manoj Hastak is Professor of Marketing (e-mail: mhastak@american. edu), and Michael B. Mazis is Professor Emeritus (e-mail: mmazis@ american.edu), Kogod School of Business, American University. Initial work on the typology was undertaken as part of a project for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding truthful but misleading claims in food labeling. The authors are grateful to Alan Levy and Nancy Crane of the FDA, Janice Albert of the Food and Agriculture Organization, and other members of the FDA project team for their valuable contributions. The authors are solely responsible for opinions expressed in the article. Lauren Block served as associate editor for this article. © 2011, American Marketing Association ISSN: 0743-9156 (print), 1547-7207 (electronic) 157 Commission (FTC) or Lanham Act decisions have been used to create typologies to describe several types of deception. Some of the typologies have been exhaustive. For example, Ford, Kuehl, and Reksten (1975) propose a classification of 13 categories of deception. This typology has been criticized as “somewhat cumbersome and the categories do not appear to be mutually exclusive” (Gardner and Leonard 1990, p. 287). This critique may also apply to Preston’s deception typologies based on case law. Preston (1989b) develops 15 categories of “deceptive implications” derived from FTC decisions and 11 categories based on Lanham Act cases (Preston 1989a). In his seminal work on deceptive advertising, Richards (1990) also relies on Preston’s typology of implied deceptive claims to address consumer comprehension of advertising claims. Petty and Kopp (1995) develop a more parsimonious set of “deceptive implications” by synthesizing Preston’s classification system into four categories. This typology provides a useful basis for identifying different types of deception that have been the focus of FTC and Lanham Act deception cases. Petty and Kopp also provide multiple examples from legal cases to illustrate the application of their typology. However, they do not provide a theoretical basis for understanding various types of deception. Some of the typologies seem to be too parsimonious. Gardner (1975) identifies a three-level typology of advertising deception: unconscionable lie, claim–fact discrepancy, and claim–belief interaction. Russo, Metcalf, and Stephens (1981) also identify three types of ad deception: fraud, falsity, and misleadingness. However, such typologies are too succinct to develop a full understanding of deception and to provide a comprehensive framework for advertising deception research. In addition, they tend to be based on practice rather than theory. These ad deception typologies distinguish between expressly false claims and implied claims that mislead consumers. In assessing express claims, courts or regulatory agencies rely on factual evidence to determine whether an Journal of Public Policy & Marketing Vol. 30 (2) Fall 2011, 157–167 158 Deception by Implication advertised claim can be substantiated on the basis of scientific evaluation. However, consumer perceptions are frequently relied on in the assessment of implied claims. For example, Preston and Scharbach (1971) note that consumers often make assumptions about the intent of the advertiser and thus draw inferences that go beyond the literal content of the advertisement. Most implied claims are literally true but may mislead consumers. As a result, our analysis focuses on these truthful but potentially misleading advertising claims. Courts and government agencies have recognized that literally truthful advertising claims may mislead consumers. For example, the FTC challenged advertisements for Kraft cheese slices that claimed the product contained five ounces of milk. Consumer research found that consumers were led erroneously to believe that the cheese slices contained as much calcium as five ounces of milk. In reality, some of the calcium was lost in processing (Federal Trade Commission v. Kraft, Inc. 1991; Stewart 1995). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has focused on claims by food producers that certain products are free from recombinant bovine somatotropin (“rBST-free”) or genetically modified organisms (“GMO-free”). The FDA has maintained that claims about the absence of bovine growth hormones or genetically modified ingredients imply to consumers that the advertised food product is safer or of higher quality than other brands in the product class (Korwek 2000). In summary, a review of the literature suggests two broad approaches to understanding various types of deception. Some researchers have developed deception typologies that are primarily based on case law and examples of deceptive practice (e.g., Petty and Kopp 1995; Preston 1989b; Richards 1990). Other researchers have relied on psychological theory to explore specific types of deception (e.g., Burke, Milberg, and Moe 1997; Pechmann 1996). However, there has not been a systematic effort to develop a typology of deception that integrates both approaches. The purpose of this article is to present a new typology of truthful but misleading advertising claims that attempts to achieve this integration. Our focus is on truthful claims with false or misleading implications rather than on claims that are patently false. In developing the typology, we rely on the work of other researchers as well as on legal cases involving deceptive advertising and labeling claims. Furthermore, we rely on a diverse set of psychological theories to provide a more comprehensive understanding of why consumers are likely to be misled by a particular type of deception. The goal is to generate a better appreciation of how consumers process various types of potentially misleading information and to explore implications for further research. Integrating consumer behavior theory into legal analyses is potentially valuable to researchers and to public policy makers because understanding how consumers process information enables public policy makers to generalize beyond a single case or public policy issue and to make valuable predictions. A theory-based typology is consistent with good public policy because when a specific case is being considered, the typology can provide a theoretical basis for arguing that a particular advertising claim is misleading and also suggest past legal precedent in finding similar advertising to be misleading. For this reason, a typology (such as the one proposed herein) supports the fact-finding process by suggesting an interpretation of a challenged claim and also by indicating how the interpretation may be tested to determine whether it is consistent with proposed theory. Typology of Truthful but Misleading Claims In this section, we identify five major types of misleading advertising claims. We also provide examples illustrating each type of misleading claim. Finally, we discuss the psychological mechanisms that may explain how consumers may be misled by each of the five claim types. Table 1 provides a summary of the five types of misleading claims. Omission of Material Facts Overview Marketers sometimes make claims in advertising or on product labels that are literally true but are misleading because a material fact or facts have been omitted. For example, the marketer may fail to disclose limiting conditions that are necessary for correct interpretation of the claim. The claim would not mislead consumers if prominent and understandable qualifications were presented. Without effective qualification, consumers may draw broad inferences from a claim based on prior experience or on the physical appearance of the product. Omissions can be classified as pure omissions or halftruths. In the former case, the marketer provides no information on the issue or attribute of interest, and in the latter case, incomplete information that leads to biased inferences is provided. Theory Consumer inferences that arise when material facts are omitted are best explained by the literature on schemas (Alba and Hasher 1983). A schema is a well-developed knowledge structure about a particular domain. For example, most U.S. consumers have a schema that contains their knowledge, beliefs, and expectations about the safety of food products. This schema has developed over time and is based on information from a variety of sources, including personal experience (“cooking foods reduces the risk of getting sick”) and information from the media (“the FDA protects the food supply”). As a result, most consumers believe that the food supply is relatively safe. An important function of a schema is to provide consumers with “default values” for information that is typical of a particular stimulus but is missing in a given description of that stimulus (Abelson 1981; Kardes 1993; Taylor and Crocker 1981). Thus, consumers will go beyond the provided information and make inferences based on the schema. For example, if there are no specific disclosures on the label of a food product regarding safety, consumers will rely on their “food safety” schema to infer that the food is safe for consumption like all other foods. If a food product has unique properties that affects its safety or creates unusual digestive problems, consumers may be misled in Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 159 Table 1. Typology of Truthful but Misleading Advertising and Labeling Claims Claim Type Definition Omission of material facts Key fact or facts have been omitted. Misleadingness due to semantic confusion Use of unclear or deliberately confusing language, symbols, or images. Intra-attribute misleadingness Claim about an attribute leads to misleading inference about the same attribute. Interattribute misleadingness Claim about an attribute leads to misleading inference about another attribute. Source-based misleadingness Endorsement by expert or consumer testimonial is biased. Claim Subtypes (1) Pure omission (2) Half-truths (1) Attribute uniqueness claims (2) Attribute performance claims (1) Expert source (2) Typical consumer source (3) Multiple sources the absence of a disclosure informing them about such problems. The effects of omission of key information on consumer inferences can also be explained by Grice’s (1975) conversational norms. Gricean theory may be particularly relevant to understanding how consumers process half-truths. Specifically, according to the “maxim of quantity” proposed by Grice, the provider of information is expected to make his or her contribution as informative as required—no more and no less. If the recipient of information (through an advertisement) applies this conversational norm, he or she will conclude that all information needed to draw valid inferences has been provided. Failure to do so will induce the recipient to generate invalid inferences and thus be deceived. Examples As an example of a pure omission of a material fact, consider the case of the fat substitute Olestra. In 1996, the FDA approved the use of Procter & Gamble’s Olestra as an ingredient in certain snack foods. The FDA’s review of clinical studies found that the product has the potential to cause gastrointestinal problems in some people. Studies also showed that Olestra-containing products might inhibit Examples Theory (1) Failure to disclose gastrointestinal upset caused by Olestra. (2) “Free” offers do not disclose relevant terms. (1) Schema theory (2) Grice’s theory of conversational norms “Fresh Italian” pasta sauce contained heat-processed tomatoes. (1) Pragmatic implication (1) “No cholesterol” claim interpreted to imply competitors contain cholesterol. (2) “Contains oat bran” claim interpreted to imply a substantial amount of oat bran. (1) Feature-absent inferences (2) Pragmatic implication “Low cholesterol” claim interpreted to imply a low amount of fat. (1) Logical or probabilistic consistency (1) A surgeon endorses a dietary supplement. (2) An extreme weight loss testimonial does not reflect typical experience. (3) The claim “recommended by more pediatricians” may not be based on a representative sample. (1) Informational influence: source expertise (2) Informational influence: source similarity (3) Social proof the absorption of certain fat-soluble vitamins and minerals. According to schema theory, a warning is needed to inform consumers of material facts about potential gastrointestinal discomfort and about potential lack of vitamin absorption resulting from consuming Olestra. In the absence of a warning, the schema default value is that both “regular” and Olestra-containing snack foods are unlikely to cause digestive discomfort. Thus, the warning is required to supply a material fact about which most consumers would be unaware. Irradiated food is another example of a situation in which a claim is potentially misleading because a material fact has been omitted. Research has shown that irradiating foods can potentially affect a product’s taste and flavor. If consumers were not informed that a particular food product is irradiated, their schema default value would likely indicate that the product would taste like regular (nonirradiated) food. Consequently, the FDA as well as regulatory agencies in many other countries requires foods that have undergone irradiation to be labeled. The logic behind this labeling requirement is that a change in the taste and texture of a food product is a material fact that should be disclosed to consumers. 160 Deception by Implication However, the FDA does not require labeling for irradiated ingredients. Its rationale is that no meaningful evidence exists that irradiation of an ingredient is likely to affect the characteristics of multiple-ingredient food in a significant way. In other words, irradiation of ingredients does not produce any material changes in the final product. In essence, the FDA does not consider irradiation itself a material fact and therefore does not require disclosure of irradiation unless it believes that the food properties, such as taste and texture, have been altered in a significant way. In contrast, some European countries (e.g., the United Kingdom) require labeling of irradiation of both finished foods and ingredients. This approach is based on the assumption that consumers have a “right to know” whether food products undergo any significant processing, such as irradiation. Thus, irradiation of foods is in and of itself considered a material fact. This example illustrates that the interpretation of what constitutes a material fact can vary across cultures and regulatory approaches. Some negative option plans provide an example of marketing representations that are half-truths. In many instances, negative options or “free” offers do not disclose all relevant terms and conditions of the offer. A recent example is the FTC (2005a) charges against Experian. Experian advertised that it provided “free credit reports” to consumers who visited the website freecreditreport.com. However, the FTC charged that the company failed to disclose that consumers who signed up to receive the free credit report would automatically be enrolled in the company’s credit monitoring service and charged $79.95 if they did not cancel within 30 days. According to Grice’s theory, consumers would assume that the credit reports were truly free without any strings attached and thus would be deceived. Research and Policy Implications It would seem that deception occurring through omission of material information could be minimized or cured through prominent disclosures. However, consumer knowledge and involvement may moderate the effectiveness of disclosures. For example, Sujan (1985) suggests that novice consumers are likely to engage in schema-driven processing even in situations in which some of the information presented to them contradicts the (default) implications of the activated schema or category. Lacking the ability to detect when detailed information contradicts schema-based default values, consumers may engage primarily in top-down processing. In contrast, experts are more likely to engage in careful piecemeal processing when they detect discrepancies between provided information and the schema. Fiske and Kinder (1981) show similar processing differences between involved and uninvolved participants in processing new information. Their research shows that less involved people rely on the activated schema to process information and thus remember schema-consistent information better than schema-inconsistent information. In contrast, involved people go beyond the activated schema to process schemainconsistent information and therefore remember both consistent and inconsistent information equally well. In a different domain, the ELM (elaboration likelihood model) posits that both motivation and ability to process information may influence the mode of information processing. Consumers who are not knowledgeable about (low ability) or are uninvolved with (low motivation) the brand are likely to engage in peripheral processing of advertising or labeling information and thus may not encode detailed information embedded within these mediums (see Johar 1995; Mitra, Raymond, and Hopkins 2008). The preceding literature has important implications for the effectiveness of disclosures. Disclosures designed to counter the effects of schema-driven processing can be viewed as providing respondents with information that is inconsistent with the activated schema. Research cited in the preceding paragraph suggests that consumers will likely process such inconsistent information only if they have both the ability and the motivation to do so. Uninvolved or low-knowledge consumers will likely rely mainly on their activated schema (and associated default values) and thus will not sufficiently process the information in the disclosure to correct their take-away from the advertisement or label. In this situation, requiring a detailed disclosure may not be the best policy solution, because the added costs of requiring the disclosure may overshadow any potential benefits. Additional research designed to further explore these predictions would be useful. Another area for research pertains to the role of complementary disclosures across media. Because there is limited opportunity for disclosures in, for example, television advertising, more detailed disclosures on the website on which the product is purchased may be an effective way to inform consumers about material facts associated with the product. Misleadingness Due to Semantic Confusion Overview Consumers may be misled by the use of confusing language or symbols in advertisements or on packages. Semantic confusion can occur because a promotional claim uses a word or phrase that is similar to a more familiar word or phrase. Such confusion is likely to cause consumers to misperceive or miscomprehend the claim. Theory The effects of semantically confusing language or images may be explained by research on pragmatic implication (Alba and Hasher 1983; Harris and Monaco 1978; Harris et al. 1989). Pragmatic implications are inferences that are strongly implied or invited rather than asserted directly. Inferences based on pragmatic implication often occur because terms or phrases used in product descriptions (1) are confusing or have more than one meaning and/or (2) strongly suggest the underlying intent of the source of such descriptions. Considerable evidence supports the ubiquity of inferences based on pragmatic implication in consumer processing of a variety of stimuli, including marketing communications (Bruno and Harris 1980; Gaeth and Heath 1987; Harris 1977, 1981; Harris et al. 1981; Harris et al. 1989). Examples In 1990, Ragu Foods introduced a line of pasta sauce described as “Fresh Italian.” However, the sauce contained Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 161 heat-processed, remanufactured tomatoes. In addition, Citrus Hill brand orange juice was labeled “Fresh Choice.” However, the product was made from frozen concentrate and contained orange oil and essence to enhance the flavor. In both cases, the manufacturers could argue that the source of the ingredients is “fresh” tomatoes or oranges. However, the claim “fresh” would likely confuse and mislead consumers because they would take the pragmatic implication that a “fresh” product contains unprocessed ingredients only. Subsequently, the line of pasta sauce was changed from “Fresh Italian” to “Fino Italian,” and the term “fresh” was dropped from the labeling of the orange juice. Stouffer Foods was found to have falsely represented the sodium content of Lean Cuisine entrées. Stouffer’s advertisements for Lean Cuisine entrées used the phrase “With less than 300 calories, controlled fat and always less than 1 gram of sodium per entree.” Consumers likely took the (pragmatic) implication that the product was low in sodium. If so, they were misled because 1 gram is equivalent to 1000 milligrams of sodium—a high amount of sodium (Andrews and Maronick 1995). Misleadingness due to semantic confusion can sometimes occur for products that refer to a particular geographic area in the brand name. Consider the case of Louisiana Hot Sauce, a well-known condiment. The manufacturer may intend the name to suggest that the product is a Cajun-style hot sauce, but a reference to Louisiana naturally leads to the pragmatic implication that the product is made in Louisiana. The degree to which consumers are misled depends on whether the phrase “Louisiana Hot Sauce” has become a commonly used or generic phrase in the language and whether the term implies a type of hot sauce rather than a place of origin to consumers. For example, consumers in the United States would be unlikely to believe that Boston baked beans, New York cheesecake, and champagne are produced in Massachusetts, New York, and France, respectively. One significant cause of misleadingness due to semantic confusion is that terms are interpreted differently in different cultures. For example, superlative terms such as “premium” and “best” are prohibited as part of descriptions of beer in the United Kingdom, whereas these terms are commonly used in the United States. British regulators seem to be concerned that consumers might interpret these terms as signifying that the particular brand of beer has a higher quality than the average beer. In the United States, such terms are regarded as “puffery”—that is, exaggerated claims that are discounted by consumers. Research and Policy Implications Several different approaches could be used to pragmatically imply a false claim. Few researchers have examined differences between different pragmatic implications in misleading consumers. In one study, Searleman and Carter (1988) examine four types of pragmatic implication: juxtaposing imperative statements (e.g., “Get a good night’s sleep. Buy Dreamon Sleeping Pills”), using comparative adjectives without stating the qualifier (e.g., “Lackluster Floor Polish gives a floor a brighter shine”), using hedge words (e.g., “Ty-One-On pain reliever may help get rid of those headaches”), and reporting of piecemeal survey evidence (e.g., “John Doe Jeans are available in more colors than Gloria Vanderbilt’s, are more sleekly styled than Sergio Valenti’s, and are less expensive than Cheryl Tiegs”). They find that though respondents confused all four types of pragmatic implication claims with the corresponding directly implied claims, they were less likely to be misled by comparative adjectives than the other three categories. Additional research examining the deception potential of different types of pragmatic implications would be useful. Misleading inferences based on pragmatic implication are likely to be difficult to correct. Available evidence suggests that instructions designed to sensitize respondents to the possibility that a communication may mislead them are not successful (Harris 1977). Detailed training sessions have achieved some success (e.g., Harris et al. 1981) but have also resulted in respondents becoming suspicious of truthful claims in the tested communications. That is, training seems to make respondents skeptical of all claims, including directly asserted statements (for a discussion, see Gaeth and Heath 1987). The problem associated with correcting misleading inferences generated by pragmatic implications is intensified by elderly consumers’ susceptibility to this form of deception. For example, Gaeth and Heath (1987, Experiment 2) show that age differences exist in the ability to discriminate between pragmatic implication and direct assertion statements. However, their findings are limited in that they studied only one type of pragmatic implication (juxtaposition of imperatives), and they found support for age differences only when respondents were allowed to examine the deceptive advertisements while answering questions. Further research designed to extend their findings to other types of pragmatic implication claims and to other “vulnerable” populations (e.g., children) would be useful. Intra-Attribute Misleadingness Overview Intra-attribute misleadingness refers to a situation in which a claim about an attribute leads to misleading inferences about the same attribute. Consumers might generate two types of misleading intra-attribute inferences when exposed to advertising or labeling claims. First, attribute uniqueness claims refer to situations in which a marketer incorrectly implies that a brand is uniquely associated with a particular attribute or feature. For example, consumers may interpret a claim such as “Brand X has no cholesterol” to mean that Brand X is the only brand without cholesterol. To the extent that adequate proof does not exist to support such uniqueness claims, the consumer may be misled. Second, attribute performance claims refer to situations in which a marketer implies incorrectly how well a brand performs on a certain attribute or feature. For example, consumers may interpret the claim “Brand X has protein” to mean that the brand is a good source of that attribute. To the extent that the brand possesses only a small amount of protein, the claim would be misleading. Similarly, marketers sometimes make representations that a brand is superior to other brands or to other formulations of their brand on an attribute (“Brand X has less fat than Brand Y”). Consumers are prone to make more general inferences about the brand on this attribute (“Brand 162 Deception by Implication X is a low-fat food”). When such inferences are erroneous, consumers are misled. Theory The effects of attribute uniqueness claims are explained by studies on “feature-absent” inferences (Burke, Milberg, and Moe 1997; Simmons and Leonard 1990). That research reveals that when a brand prominently features an attribute that is not typically discussed on labels or in advertising (e.g., amount of vitamin K in a food), consumers may infer that other brands in the category do not possess that attribute. Because the attribute has been neglected by marketers in the past, consumers may assume that a typical brand in the category does not possess the attribute. Consequently, mention of the attribute by one brand leads to the inference that this brand uniquely possesses that attribute. The effects of attribute performance claims are accounted for by the concept of pragmatic implication, which we discussed in the “Misleadingness due to Semantic Confusion” section. Specifically, these inferences likely occur because consumers convert explicitly stated information into its probable underlying intent (Alba and Hasher 1983). For example, when consumers interpret the claim “brand X has protein” to mean that the brand is a good source of protein, this is based on the assumption that such an interpretation is intended by the marketer. The expectation is that the marketer would not make such a claim if the product contained only a trivial amount of the nutrient. A similar logic explains why consumers interpret a superiority claim such as “brand X has less fat than brand Y” to mean that brand X is a low-fat food. Examples When Mazola vegetable oil made a “no cholesterol” claim on its product label, the FDA was concerned that consumers might interpret this as a uniqueness claim. In reality, no brand of vegetable oil contains cholesterol. Thus, although the express claim is literally true, the likely implied claim (of uniqueness) is false because it may imply to consumers that only that brand is cholesterol free. In the 1980s, when claims about the health benefits of eating fiber were ubiquitous, companies made claims such as “made with fiber” or “contains fiber” for products such as doughnuts. Because these doughnuts contained an insignificant amount of fiber, consumers were likely misled by such claims. More generally, if a health claim is made for a particular nutrient, consumers are likely to infer (through pragmatic implication) that the product making such a health claim has a reasonable level of the nutrient. One approach to preventing these types of misleading claims is to establish minimum nutrient levels that must be met before a marketer can make such claims. Candy companies have developed lower-fat versions of popular candy bars in an effort to appeal to consumers concerned about the relatively high fat and calorie content of most candy bars on the market. Although companies might desire to promote these “lower-fat” versions with claims such as “30% less fat than regular candy bars” on labels and in advertising, even with a 30% reduction in fat, these candy bars may still contain a significant amount of fat. Nevertheless, the concept of pragmatic implication suggests that con- sumers will incorrectly assume that the intent of the manufacturer is to convey that the candy bar is a low-fat food. In addition, companies frequently refer to a fruit juice, such as apple, orange, or cranberry juice, in their product names or as part of a claim on package labels. Because most of these products contain at least some fruit juice, these claims are literally true. However, in the absence of information to the contrary, consumers may infer incorrectly that all these products contain 100% fruit juice. In a similar vein, POM Wonderful recently sued several beverage manufacturers, including Coca-Cola, Welch’s, and Ocean Spray, for advertising that their fruit juice blends are grape–pomegranate or cranberry–pomegranate blends. Although it is literally true that these beverages contain pomegranate juice, which is high in antioxidants, the juice blends typically have a small amount of pomegranate juice and largely contain apple juice (Hyland 2009). One approach to eliminate consumer misperceptions could be to require labeling of the percentage of juice content for all products purporting to contain fruit and vegetable juices. Such a requirement might enable consumers to determine the relative juice content of competing products. Research and Policy Implications The FDA has long been concerned with marketing claims about nutrients that erroneously convey to consumers that the product has a smaller amount of an undesirable nutrient than is, in reality, the case. Before the passage of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (Pub. L. 101-53) in 1990, marketers were able to make claims such as “reduced fat” or “light” without any requirements for nutrient (fat) content. With the passage of the act, the FDA set standards for many of these claims. For example, for a “fat-free” claim, the product must have less than .5 grams of fat per serving, and a “low-fat” claim is allowed for products with no more than 3 grams of fat per serving. Other claims, including “reduced fat,” “low cholesterol,” “light,” and “healthy,” also have FDA-designated minimum requirements. More recently, there have been calls for the FDA to specify qualifying nutrient levels for carbohydrate-related claims. Food marketers are increasingly using claims such as “low carb,” “reduced carb,” and “carb smart.” However, little research has examined how consumers interpret these claims and whether they are misled by them. Particularly noteworthy are situations in which the product’s brand name connotes or implies performance on a particular attribute or function that is false or misleading. For example, many weight loss products use names that suggest that the product will help people lose weight. In 2000, as a part of a settlement, the FTC (2002a, 2005b) ordered Enforma Natural Products to stop using the names “fat trapper” and “fat trapper plus” for two of its weight loss products unless it could produce reliable evidence that the products cause weight loss. The name “fat trapper” likely communicated to consumers that the product trapped fat in the body and thus caused weight loss. Moreover, it is unlikely that any disclosure designed to convey that the product does not cause weight loss by itself (i.e., without diet and exercise) is likely to be effective. Consequently, banning the use of the brand name may be the only possible solution. However, this is a rather drastic remedy. Research Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 163 examining the effects of disclosures designed to correct the potentially misleading effects of brand names is virtually nonexistent and would prove most useful to illuminate appropriate action in such situations.1 Interattribute Misleadingness Overview Consumers may rely on a claim for one attribute (“Brand X is low in cholesterol”) to infer a claim on another attribute (“Brand X is low in fat”). The inference occurs because consumers believe (rightly or wrongly) that the two attributes are correlated. To the extent that the inferred claim is false, consumers are misled. Theory Evidence that consumers process information in this manner comes from literature on inferences based on logical or probabilistic consistency. This literature suggests that prior knowledge and expectations of the association between two attributes (“brands that are low in cholesterol are also low in fat”) influences information processing when information about only one of the two attributes (e.g., cholesterol) is provided. Several studies have shown inference making in this manner (e.g., Andrews, Netemeyer, and Burton 1998; Broniarczyk and Alba 1994; Dick, Chakravarti, and Biehal 1990; Ford and Smith 1987; Huber and McCann 1982; Roe, Levy, and Derby 1999). The problem of potentially erroneous inferences generated by means of logical consistency is exacerbated by a phenomenon termed “conservatism” or “belief perseverance” (Lord, Ross, and Lepper 1979). Research in this area suggests that when people form an inference or belief, they tend to hold onto that belief even when confronted with evidence that directly challenges it. This problem is particularly acute when the evidence challenging a prior belief is ambiguous or difficult to interpret (e.g., Hoch and Deighton 1989; Hoch and Ha 1986). Thus, for example, if a product label says “low in cholesterol,” consumers may rely on logical consistency to infer that the product is low in fat even if the label discloses the actual grams of fat in the product. The reason is that numerical information about nutrients is ambiguous and difficult to interpret for many consumers (Viswanathan 1994; Viswanathan and Hastak 2002; Viswanathan, Hastak, and Gau 2009). In such a case, setting qualifying standards or banning the claim might be more appropriate than merely disclosing the grams of fat in the product. Examples Foods such as cakes and pastries are often marketed as being low in fat to make them more appealing to weightconscious consumers. Consumers may infer on the basis of logical consistency that such products are also low in calories. However, they may be misled because many of these foods contain a high number of calories. Similarly, most brands of potato chips contain no cholesterol. However, a 1Generalized performance-suggesting names such as Slimfast seem to be allowed in general. Only names that specifically and falsely suggest a particular method of performance are not allowed (e.g., Fat Trapper) or are allowed with disclosure (e.g., Aspercreme). brand making a “no cholesterol” claim may be erroneously perceived as low in saturated fat as well. Dairy cows are sometimes treated with a growth hormone called rBST to increase milk production. Milk producers that market milk from cows not treated with rBST have sought to label their product “rBST-free.” A logical inference that consumers could draw from such labeling is that this milk is safer and/or of higher quality than milk from rBST-treated cows. To the extent that such an inference is not supported by scientific data, consumers may be misled. From 1988 to 1996, Doan’s advertised its analgesic products as having a “unique” ingredient that “other pain relievers don’t have.” This is a literally true statement. However, consumers inferred incorrectly that as a result of this “special” ingredient, Doan’s was more effective than other analgesic products for back pain relief (Mazis 2001). A more recent example is DanActive dairy drink. Dannon’s advertisements for DanActive made the express claim that the product is “clinically proven to help strengthen your body’s defenses.” The FTC (2010) argued that the advertisements conveyed (by implication) that the product reduces the likelihood of getting a cold or flu, an unsubstantiated claim. Most consumers likely perceive a correlation between stronger body defenses and lower susceptibility to colds and flu. Thus, information on one attribute likely leads to inferences about the other. Research and Policy Implications Consumers’ tendency to cling to their inferences even in the face of contrary information may pose a particularly significant problem for low-literate consumers. In their review, Viswanathan, Rosa, and Harris (2005) note that as many as one-fourth of the adult U.S. population lacks even rudimentary language and numeracy skills. They further suggest that functionally illiterate consumers tend to rely more on concrete thinking and pictographic information to make judgments and decisions. Consequently, numerical or verbal disclosures presented to correct incorrect inferences based on advertising or label information may be particularly ineffective with these customer segments (Viswanthan, Hastak, and Gau 2009). This is both an important and worthwhile research area with significant policy implications. The literature on “conservatism” or “belief perseverance” discussed previously also may be particularly relevant to situations in which consumers receive “corrective” disclosures some time after they have been exposed to misleading or deceptive claims. For example, in many instances, consumers are exposed to deceptive claims in advertising or sales presentations and subsequently receive “corrective” disclosures closer to the moment of purchase. In these cases, even clear and conspicuous disclosures may not be effective because of consumers’ tendency to assimilate new information with past beliefs. The FTC seems to be sensitive to this problem. In its policy statement on deception, the FTC (1983) notes that “Oral statements, label disclosures, or point-of-sale material will not necessarily correct a deceptive representation or omission. Thus, when the first contact between a seller and buyer occurs through a deceptive practice, the law may be violated even if the truth is subsequently made known to the purchaser.” The efficacy 164 Deception by Implication of disclosures (or lack thereof) provided some time (i.e., days rather than minutes) after initial contact with deceptive information has not received attention in the literature and constitutes an important unexplored area. Source-Based Misleadingness Overview Consumers are frequently exposed to endorsements by expert individuals or organizations (“expert source”) or to testimonials by ordinary users of the product (“typical consumer source”). However, there are many situations in which such endorsements may mislead consumers. First, when the “expert” offers an opinion about an issue outside his or her area of expertise, consumers may be misled. Second, consumers may be misled when the expert or endorsing organization has a relationship with the marketer and does not provide an unbiased opinion. Third, when marketers assert that a majority of relevant experts endorse the product, consumers may assume that this involves a representative sampling of experts. However, in some cases, a marketer will present only the opinions of experts who favor the product. Fourth, a marketer might prominently mention a credible organization on its product label, leading consumers to assume erroneously that the product has been endorsed by the organization. Finally, when consumer testimonials are presented, consumers may assume that these involve a representative sampling of users and/or that these users are disinterested consumers. However, a marketer may present only the opinions of satisfied users and/or of family members or friends. Theory Social influence theory provides a basis for conceptualizing the effects of various sources on consumer perceptions and evaluations. Specifically, the concept of informational social influence that Deutsch and Gerard (1955) proposed refers to the tendency to accept information from others as evidence of reality (see also Bearden, Netemeyer, and Teel 1989; Burnkrant and Cousineau 1975; Dean and Biswas 2001; Martin, Wentzel, and Tomczak 2008).2 Both expert endorsers (either individuals or third-party organizations) and typical consumer endorsers likely produce informational influence through the internalization process. Specifically, consumers tend to accept the recommendations of the endorser because of either the endorser’s expertise or the similarity of the endorser to themselves. In situations in which multiple endorsers (either experts or consumers) are employed, the influence generated by the endorsers may be further enhanced by social proof. Social proof suggests that people are more likely to imitate the actions of a large group than the actions of just one person because they tend to reason that if a lot of people are doing something, they must be right (Cialdini 2001). Examples An example of an expert offering an opinion outside his or her area of expertise might be a surgeon endorsing a dietary 2The concept of informational social influence is similar to the process of internalization that Kellman (1958, 1961) postulates. supplement. Consumers may be misled if they assume that the surgeon has nutritional expertise, thus creating informational influence. As another example, Dura Lube advertisements featured a former NASA astronaut. According to the FTC (1999b), Dura Lube represented that the astronaut had expertise in the evaluation of automobile engine lubrication and that he endorsed Dura Lube by means of independent, objective, and valid testing. However, the astronaut was not an expert in automobile engine lubrication, and he had not endorsed the product using scientific testing. In addition, some marketers create and/or support “independent”-sounding organizations that then endorse the marketer’s products or positions. Consumers may infer that this organization provides an unbiased expert opinion and thus may be subject to informational influence. Screen Test U.S.A. tried to convince consumers that it could assist them in getting their children modeling jobs if they purchased its services. To add credibility to their activities, Screen Test U.S.A. claimed that it was endorsed by the American Child Actor and Modeling Association. However, this association was a shell corporation created by the owner of Screen Test U.S.A. (FTC 1999a). An infant formula manufacturer might make the claim “recommended by more pediatricians than any other formula.” This type of a claim operates through informational influence involving an expert source (pediatricians) and through social proof (i.e., most pediatricians recommend the product). In reality, 80% of the pediatricians surveyed might have expressed no preference for any one formula. Thus, although this claim may be literally true, the implication that a majority of pediatricians prefer the formula is misleading. An orange juice manufacturer might include a reference to the American Heart Association’s recommendation to eat more fruit and vegetables. Consumers would be misled if they inferred that the American Heart Association endorses this brand of orange juice as a means to prevent heart disease. Research and Policy Implications By many accounts, source-based misleadingness is on the rise. In particular, the use of consumer testimonials (i.e., endorsements by typical users of a product) is widespread. While consumer testimonials are popular in a wide variety of product categories, they are ubiquitous in advertising for dietary supplements, weight loss products, and business opportunity services. For example, in a 2002 content analysis of weight loss advertisements disseminated through various media (e.g., television, radio, magazines, newspapers, direct mail, websites), the FTC (2002b) found that 65% of all advertisements used consumer testimonials. Furthermore, the FTC found that the use of consumer testimonials appearing in weight loss advertisements in select magazines (i.e., Family Circle, Cosmopolitan, Women’s Day, Glamour, McCall’s, Ladies Home Journal, Self, and Redbook) increased significantly, from 12.5% in 1992 to 76% in 2001. However, although many academic studies have examined celebrity endorsers, the effects of typical consumer endorsements and testimonials have received limited attention (for exceptions, see Feick and Higie 1992; Martin, Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 165 Wentzel and Tomczak 2008). Moreover, the literature has focused more on the effects of testimonials on product evaluations than on deception and miscommunication issues. Two unpublished studies commissioned by the FTC that address these issues were recently released (in 2009) as a part of its review of its endorsement guides. The studies (Hastak and Mazis 2003; Hastak and Mazis 2004) tested the effects of consumer testimonials on a variety of products (e.g., weight loss, dietary supplement, business opportunity) and found that consumer testimonials do communicate that product users will achieve results similar to those portrayed in the advertisements and that most “corrective” disclosures (including “results not typical”) do not significantly reduce this communication. Only one disclosure (tested only for a weight loss product), which stated how much weight the average user loses using the product (the “average results” disclosure), significantly reduced such communication. Partly from these studies’ findings, the FTC adopted new endorsement guides (in October 2009) that explicitly reject disclaimers such as “results not typical” and require instead a disclaimer that informs consumers about the results they may realistically expect to achieve (e.g., how much weight would a typical user lose after using the product) (FTC 2009). However, this is clearly an area in need of additional research. For example, although the Hastak and Mazis (2003, 2004) studies tested several products, it is unclear whether the deceptive effects of testimonials vary by product type. Furthermore, the economics of information literature suggests that products can be classified into “search” and “experience” categories. Search products can be evaluated before purchase, whereas experience products must be consumed or used before they can be evaluated. The literature suggests that consumers are less likely to be skeptical of search products than experience products because search product claims can be verified more easily before purchase (see Ford, Smith, and Swasy 1990). Thus, consumer testimonials may be more effective for search products. Other issues worthy of investigation include the effects of single versus multiple testimonials; multiple testimonials with homogeneous versus heterogeneous experiences; and individual difference variables, such as locus of control, ad skepticism, and susceptibility to normative influence as moderating variables. explain to students the importance of psychological theories in understanding consumer behavior. Furthermore, the many unaddressed issues and questions highlighted herein should provide a fertile ground for enriching class discussion and fostering deeper inquiry. In addition, we believe that the typology offers the potential for improving the quality of expert opinions presented in deceptive advertising cases. Such expert opinions are increasingly being confronted in court through Daubert challenges (Ford 2005), which call into question the scientific basis for opining about consumer perceptions of advertising and labeling claims. Although expert opinion sometimes relies on specific theoretical concepts drawn from the marketing and psychological literature to bolster the proffered opinion (e.g., Federal Trade Commission v. Telebrands, TV Savings LLC, and Ajit Khubani 2005; Mazis 2001), there is no comprehensive framework in the literature that deals with the various deceptive implied claims and their psychological/theoretical underpinnings. We believe that the typology and framework proposed provides a stronger basis for building expert analysis and opinion than has been available heretofore. Finally, the typology should help develop a better understanding of deception, which, we hope, will foster a new steam of academic research in the field. We expect that the theories presented will encourage researchers to develop theory-driven research hypotheses about the effects of deceptive advertising on consumers and about approaches for enhancing the effectiveness of advertising disclosures. To that end, we have presented several research ideas that should provide a starting point for fruitful academic research studies. Conclusion ———,Richard G. Netemeyer, and Scot Burton (1998), “Consumer Generalization of Nutrient Content Claims in Advertising,” Journal of Marketing, 62 (October), 62–75. In this article, we present a new typology of truthful but misleading advertising and labeling claims. The typology relies on theoretical frameworks in cognitive and social psychology to develop a rich understanding of why consumers are likely to be misled by particular types of advertising and labeling claims. We provide numerous examples from the marketplace and from FTC and FDA cases to illustrate the elements of the typology. We believe that the typology is beneficial for pedagogy, litigation, and academic research. The typology should assist pedagogy by providing students with insights into the types of implied claims that are the source of controversy between regulators and marketers. Moreover, the theory and the examples presented should help students understand the theoretical underpinnings of challenged advertising claims. The theoretical discussion should help faculty References Ableson, Richard P. (1981), “Psychological Status of the Script Concept,” American Psychologist, 36 (7), 715–29. Alba, Joseph W. and Lynn Hasher (1983), “Is Memory Schematic?” Psychological Bulletin, 93 (2), 203–231. Andrews, J. Craig and Thomas J. Maronick (1995), “Advertising Research Issues from FTC Versus Stouffer Foods Corporation,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 14 (Fall), 301–309. Bearden, William O., Richard G. Netemeyer, and Jesse E. Teel (1989), “Measurement of Consumer Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influence,” Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (March), 473–81. Broniarczyk, Susan M. and Joseph W. Alba (1994), “The Role of Consumers’ Intuitions in Inference Making,” Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (December), 393–407. Bruno, Kristin. J. and Richard. J. Harris (1980), “The Effect of Repetition on the Discrimination of Asserted and Implied Claims in Advertising,” Applied Psycholinguistics, 1, 317–21. Burke, Sandra J., Sandra J. Milberg, and Wendy W. Moe (1997), “Displaying Common but Previously Neglected Health Claims on Product Labels: Understanding Competitive Advantages, Deception, and Education,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 16 (Fall), 242–55. 166 Deception by Implication Burnkrant, Robert E. and Alain Cousineau (1975), “Informational and Normative Social Influence in Buyer Behavior,” Journal of Consumer Research, 2 (3), 206–215. ——— (2005a), “Marketer of ‘Free Credit Reports’ Settles FTC Charges,” FTC Press Release, (August 16), [available at http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2005/08/consumerinfo.shtm]. Cialdini, Robert B. (2001), Influence: Science and Practice, 4th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ——— (2005b), “Sellers of ‘Fat Trapper Plus’ and ‘Exercise in a Bottle’ Banned from Advertising Weight-Loss Products,” FTC Press Release, (January 18), [available at http://www.ftc. gov/opa/2005/01/enforma.shtm]. Dean, Dwane Hall and Abhijit Biswas (2001), “Third-Party Organization Endorsement of Products: An Advertising Cue Affecting Consumer Prepurchase Evaluation of Goods and Services,” Journal of Advertising, 30 (4), 41–57. Deutsch, Morton and Harold. B. Gerard (1955), “A Study of Normative and Informational Influences upon Individual Judgment,” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51 (3), 629–36. Dick, Alan D., Dipankar Chakravarti, and Gabriel Biehal (1990), “Memory-Based Inferences During Consumer Choice,” Journal of Consumer Research, 17 (June), 82–93. Federal Trade Commission v. Kraft, Inc. (1991), Final Order, Docket No. 9208, (January 30), Lexis 38. Federal Trade Commission v. Telebrands, TV Savings LLC, and Ajit Khubani (2005), Commission Decision, Docket No. 9313. Feick, Lawrence and Robin A. Higie (1992), “The Effects of Preference Heterogeneity and Source Characteristics on Ad Processing and Judgments about Endorsers,” Journal of Advertising, 21 (2), 9–24. Fiske, Susan T. and Donald R. Kinder (1981), “Involvement, Expertise, and Schema Use: Evidence from Political Cognition,” in Personality, Cognition, and Social Interaction, N. Cantor and J.F. Kihlstrom, eds. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 181–90). Ford, Gary T. (2005), “The Impact of the Daubert Decision on Survey Research Used in Litigation,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 24 (2), 234–52. Ford, Gary T., Philip G. Kuehl, and Oscar Reksten (1975), “Classifying and Measuring Deceptive Advertising: An Experimental Approach,” in Combined Proceedings, Edward M. Mazze, ed. Chicago: American Marketing Association, 493–97. ———, Darlene B. Smith, and John L. Swasy (1990), “Consumer Skepticism of Advertising Claims: Testing Hypotheses from Economics of Information,” Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (March), 433–41. ———and Ruth A. Smith (1987), “Inferential beliefs in Consumer Evaluations: An Assessment of Alternative Processing Strategies,” Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (December), 363–71. FTC (1983), “FTC Policy Statement on Deception,” 103 F.T.C. 110, 174, [available at http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/policystmt/addecept.htm]. ——— (1999a), “Bogus ‘Talent Scouts’ Use Smoke Screen to ‘Screen Test’ Consumers,” FTC Press Release, (May 27), [available at http://www.ftc.gov/opa/1999/05/screen.shtm]. ———(1999b), “FTC Charges Motor Oil Additive Marketer,” FTC Press Release, (May 4), [available at http://www.ftc. gov/opa/1999/05/duralub2.shtm]. ——— (2002a), “FTC Seeks Civil Contempt Liability for Defendants’ Violations of Court Order,” FTC Press Release, (January 10), [available at http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2002/01/enforma. tshtm]. ———(2002b), “Weight-Loss Advertising: An Analysis of Current Trends,” FTC Staff Report, (September), [available at http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/reports/weightloss.pdf]. ——— (2009), “Marketers of ‘Ab Force’ Weight Loss Device Agree to Pay $7 Million for Consumer Redress,” FTC Press Release, (January 14), [available at http://www.ftc.gov/ opa/2009/01/telebrands.shtm]. ——— (2009), “FTC Publishes Final Guides Governing Endorsements, Testimonials,” FTC Press Release, (October 5), [available at http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2009/10/endortest.shtm]. ——— (2010), “Dannon Agrees to Drop Exaggerated Health Claims for Activia Yogurt and DanActive Dairy Drink,” FTC Press Release, (December 15), [available at http://www. ftc.gov/opa/2010/12/dannon.shtm]. Gaeth, Gary J. and Timothy B. Heath (1987), “The Cognitive Processing of Misleading Advertising in Young and Old Adults: Assessment and Training,” Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (June), 43–54. Gardner, David M. (1975), “Deception in Advertising: A Conceptual Approach,” Journal of Marketing, 39 (January), 40–46. ———and Nancy H. Leonard (1990), “Research in Deceptive and Corrective Advertising: Progress to Date and Impact on Public Policy,” in Current Issues and Research in Advertising, Vol. 12, James H. Leigh and Claude R. Martin, eds. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 275–309. Grice, H. Paul (1975), “Logic and Conversation,” in Syntax and Semantics: Speech Acts, P. Cole and J. L. Morgan, eds. New York: Academic Press, 41–58. Harris, Richard J. (1977), “Comprehension of Pragmatic Implications of Advertising,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 62 (5), 603–608. ———(1981), “Inferences in Information Processing,” in The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, Vol. 15, Jose P. Mestre and Brian H. Ross, eds. Waltham, MA: Academic Press, 81– 128. ———,Tony M. Dubitsky, James Connizzo, Larry E. Letcher, and Cindy S. Ellerman (1981), “Training Consumers About Misleading Advertising: Transfer of Training and Effects of Specialized Knowledge,” Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 3, 105–122. ——— and Gregory E. Monaco (1978), “The Psychology of Pragmatic Implication: Information Processing Between the Lines,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 107 (1), 1–22. ———, Michael L. Trusty, John I. Bechtold, and Louise Wasinger (1989), “Memory for Implied Versus Directly Stated Advertising Claims,” Psychology and Marketing, 6 (2), 87–96. Hastak, Manoj and Michael B. Mazis (2003), “The Effect of Consumer Testimonials and Disclosures on Ad Communication for a Dietary Supplement,” report submitted to the Federal Trade Commission, [available at http://www.ftc.gov/ reports/endorsements/study1/report.pdf]. ——— and ——— (2004), “Effects of Consumer Testimonials in Weight Loss, Dietary Supplement and Business Opportunity Advertisements,” report submitted to the Federal Trade Commission, [available at http://www.ftc.gov/reports/endorsements/ study2/report.pdf]. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 167 Hoch, Stephen J. and John Deighton (1989), “Managing What Consumers Learn from Experience,” Journal of Marketing, 53 (April), 1–20. Preston, Ivan L. (1989a), “False and Deceptive Advertising Under the Lanham Act: Analysis of Factual Findings and Types of Evidence,” The Trademark Reporter, 79 (4), 508–553. ——— and Young-Won Ha (1986), “Consumer Learning: Advertising and the Ambiguity of Product Experience,” Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (October), 221–33. ——— (1989b), “The Federal Trade Commission’s Identification of Implications as Constituting Deceptive Advertising,” University of Cincinnati Law Review, 57 (4), 1243–310. Huber, Joel and J. McCann (1982), “The Impact of Inferential beliefs on Product Evaluations,” Journal of Marketing Research, 14 (August), 324–33. ——— and Steven E. Scharbach (1971), “Advertising: More Than Meets the Eye?” Journal of Advertising Research, 11 (3), 19– 24. Hyland, Alexa (2009), “Juice Maker Squeezes Back with Aggressive Tactics,” Los Angeles Business Journal, (February 9), [available at http://www.allbusiness.com/consumer-products/ food-beverage-products/11801794-1.html]. Richards, Jef I. (1990), Deceptive Advertising: Behavioral Study of a Legal Concept. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Johar, Gita V. (1995), “Consumer Involvement and Deception from Implied Advertising Claims,” Journal of Marketing Research, 32 (August), 267–79. Roe, Brian, Alan S. Levy, and Brenda M. Derby (1999), “The Impact of Health Claims on Consumer Search and Product Evaluation Outcomes: Results from FDA Experimental Data,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 18 (Spring), 89–105. Kahneman, Daniel and Amos Tversky (1973), “On the Psychology of Prediction,” Psychological Review, 80 (4), 237–51. Russo, J. Edward, Barbara Metcalf, and Debra Stephens (1981), “Identifying Misleading Advertising,” Journal of Consumer Research, 8 (September), 119–31. Kardes, Frank R. (1993), “Consumer Inference: Determinants, Consequences, and Implications for Advertising,” in Advertising Exposure, Memory, and Choice, A.A. Mitchell, ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 163–91. Searleman, Alan and Helen Carter (1988), “The Effectiveness of Different Types of Pragmatic Implications Found in Commercials to Mislead Subjects,” Applied Cognitive Psychology, 2 (4), 265–72. Kelman, Herbert C. (1958), “Compliance, Identification, and Internalization: Three Processes of Attitude Change,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2 (1), 51–60. Simmons, Carolyn J. and Nancy H. Leonard (1990), “Inferences About Missing Attributes: Contingencies Affecting the Use of Alternative Information Sources,” in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 17, Marvin E. Goldberg, Gerald Gorn, and Richard W. Pollay, eds. Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 266–74. ——— (1961), “Processes of Opinion Change,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 25 (Spring), 57–78. Korwek, Edward L. (2000), “Labeling Biotech Foods: Opening Pandora’s Box?” Food Technology, 54 (March), 38–42. Lord, Charles, Lee Ross, and Mark Lepper (1979), “Biased Assimilation and Attitude Polarization: The Effect of Prior Theories on Subsequently Considered Evidence,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 (11), 2098–2109. Martin, Brett A.S., Daniel Wentzel, and Torsten Tomczak (2008), “Effects of Susceptibility to Normative Influence and Type of Testimonial on Attitudes Toward Print Advertising,” Journal of Advertising, 37 (1), 29–43. Mazis, Michael B. (2001), “FTC v. Novartis: The Return of Corrective Advertising?” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 20 (Spring), 114–22. Mitra, Anu, Mary Ann Raymond, and Christopher D. Hopkins (2008), “Can Consumers Recognize Misleading Advertising Content in a Media Rich Online Environment?” Psychology & Marketing, 25 (7), 655–74. Pechmann, Cornelia (1996), “Do Consumers Overgeneralize OneSided Comparative Price Claims, and Are More Stringent Regulations Needed?” Journal of Marketing Research, 23 (May), 150–62. Petty, Richard E. and John T. Cacioppo (1996), “Addressing Disturbed and Disturbing Consumer Behavior: Is It Necessary to Change the Way We Conduct Behavioral Science?” Journal of Marketing Research, 33 (February), 1–8. Petty, Ross D. and Robert J. Kopp (1995), “Advertising Challenges: A Strategic Framework and Current Review,” Journal of Advertising Research, 18 (March–April), 41–55. Stewart, David W. (1995), “Deception, Materiality and Survey Research: Some Lessons from Kraft,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 14 (Spring), 15–28. Sujan, Mita (1985), “Consumer Knowledge: Effects on Evaluation Strategies Mediating Consumer Judgments,” Journal of Consumer Research, 12 (1), 31–46. Taylor, Shelly E. and Jennifer Crocker (1981), “Schematic Basis of Social Information Processing,” in Social Cognition: The Ontario Symposium, Vol. 1, E.T. Higgins, C.P. Herman, and M.P. Zanna, eds. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 89–134. Viswanathan, Madhubalan (1994), “The Influence of Summary Information on the Usage of Nutrition Information,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 13 (1), 48–60. ———and Manoj Hastak (2002), “The Role of Summary Information in Facilitating Consumers’ Comprehension of Nutrition Information,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 21 (2), 305–318. ———, ———, and Roland Gau (2009), “Understanding and Facilitating the Usage of Nutritional Labels by Low-Literate Consumers,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 28 (2), 135–45. ———, Jose A. Rosa, and James E. Harris (2005), “Decision Making and Coping of Functionally Illiterate Consumers and Some Implications for Marketing Management,” Journal of Marketing, 69 (January), 15–31. Copyright of Journal of Public Policy & Marketing is the property of American Marketing Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.