Uploaded by

common.user89609

American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD)

advertisement

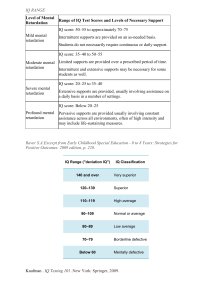

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302393580 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) Chapter · January 2013 DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_1820 CITATIONS READS 6 5,871 2 authors, including: Marc J. Tassé The Ohio State University 119 PUBLICATIONS 3,380 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: ICD-11 and defining intellectual disability. View project Technology Project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Marc J. Tassé on 19 October 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 1 [AAIDD.ORG] Marc J. Tassé & Matthew Grover Nisonger Center – UCEDD The Ohio State University 1581 Dodd Drive Columbus, OH 43210 USA Membership as of (February 2011) The American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities counts approximately 3,500 interdisciplinary members. The membership structure includes professionals working in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities. Members can select from a tiered membership menu: basic, classic, standard and premium. AAIDD is primarily a North American professional association but it also offers an “international” membership option and has international members from 55 countries. Finally, there is also a corporate membership where an agency can join garnering a reduction on membership dues for employees affiliated with the corporate member. The Association membership have the option of joining any of its 10 professional divisions (e.g., Administration, Education, Psychology, etc.), 7 Special Interest Groups (e.g., DD and co-occurring mental health problems, Technology, etc.), and 4 Action Groups (e.g. Health and Wellness, Criminal Justice, etc.). Major Areas or Mission Statement: AAIDD promotes progressive policies, sound research, effective practices, and universal human rights for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. AAIDD has adopted a 13-point set of principles (or core values) relative to its mission: Achieving full societal inclusion and participation of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Advocating for equality, individual dignity and other human rights. Expanding opportunities for choice and self-determination. Influencing positive attitudes and public awareness by recognizing the contributions of people with intellectual disabilities. Promoting genuine accommodations to expand participation in all aspects of life. Aiding families and other caregivers to provide support in the community. Increasing access to quality health, education, vocational, and other human services and supports. Advancing basic and applied research to prevent or minimize the effects of intellectual disability and to enhance the quality of life. Cultivating and providing leadership in the field. Seeking a diversity of disciplines, cultures, and perspectives in our work. Enhancing skills, knowledge, rewards and conditions of people working in the field. 1 REFERENCE: Tassé, M. J. & Grover, M. D. (2013). American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (pp. 122-125). In F. R. Volkmar (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders. New York: Springer. http://www.springer.com/us/book/9781441916976 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3 1 Encouraging promising students to pursue careers in the field of disabilities. Establishing partnerships and strategic alliances with organizations that share our values and goals. AAIDD’s Goals: 1. Enhance the capacity of professionals who work with individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2. Participate in the development of a society that fully includes individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. 3. Build an effective, responsive, well managed, responsibly-governed, and sustainable organization. Landmark Contributions AAIDD was founded in 1876 and has since been the leader in setting the practice standards, publishing books, tests and other resources, and influencing policy. AAIDD’s first president in 1876 was the French physician Édouard Séguin, MD, regarding by many as the father of special education in US. The AAIDD has led the field in establishing the definition and diagnostic criteria for intellectual disability for over a century. It is well established that a significant proportion of individuals with an autism spectrum disorder also has co-occurring intellectual disability. Since its first definition of intellectual disability in 1905, AAIDD has revised its definition 10 times to reflect the changes in research and understanding of this condition. The AAIDD definition of intellectual disability has historically been adopted by all federal and state governments as well as the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in defining intellectual disability. AAIDD is considered the professional authority in the area of intellectual disability. In examining the history of the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) one quickly discovers that the association has undergone a number of changes since it was founded in 1876. Chief among these changes is the position of the organization with regards to issues such as: (a) etiology of the disability (b) systems of classification and (c) systems of support/intervention. The AAIDD was founded by a small group of superintendants of institutions for people with disabilities. The AAIDD’s first annual meeting was held at the Pennsylvania Training School in Media, Pennsylvania on June 6th, 1876 (Sloan & Stevens, 1976), where it was founded under the name of “Association of Medical Officers of American Institutions for Idiotic and Feebleminded Persons” (Sloan & Stevens, 1976). The Association’s first constitution provided a framework for the goals of the association during these earlier days (Sloan & Stevens, 1976, p. 1): Article II: The object of the Association shall be the discussion of all questions relating to the causes, conditions, and statistics of idiocy, and to the management, training, and education of idiots and feebleminded persons; it will also lend its influence to the establishment and fostering of institutions for this purpose. Although the Association’s policies have evolved over time, the common goal of reaching a better understanding of intellectual disability and serving to improve the lives of those with intellectual disability has remained unchanged throughout the years. Changes in the Association’s name serve somewhat of a barometer for the shifting attitudes towards individuals with intellectual disability within society at large. Association name changes have largely been driven by a move away from historical terminology that has acquired increasingly pejorative connotations. In 1906, the name of the association was changed to, “The American Association for the Study of the Feebleminded.” This was the first of several name changes for the association. The name was changed again in 1933 to, “The American Association on Mental Deficiency,” which it remained until 1987, when it officially became known as the, “American Association 2 on Mental Retardation.” The most recent change came in 2007, bringing with it the current name, “American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.” This change was driven by the increasing acceptance of intellectual disability as the replacement terminology for mental retardation. AAMR also chose to include “developmental disabilities” in its name to reflect its mission and influence in areas such as autism spectrum disorders, and other related developmental disabilities. A landmark change brought about by AAIDD was in 1959 when it introduced the construct of adaptive behavior into its definition of intellectual disability (Heber, 1959). The 1959 AAIDD terminology and classification manual first introduced deficits in adaptive functioning as part of the diagnostic criteria for intellectual disability. All other major diagnostic systems (e.g., World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders) as well as federal and state agencies followed suit. AAIDD also published the first standardized measure of adaptive behavior in 1969 – titled the AAMD Adaptive Behavior Scale (Nihira, Foster, Shellhaas, & Leland, 1969). AAIDD has long been active in influencing legislation and social action towards improving treatment and supports for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In recent years, the organization has joined with other like-minded organizations such as The Arc of the United States to form the Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities, which advocates for public policy dedicated to the empowerment of people with disabilities (Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2010). Throughout the years, AAIDD has served as amicus curiae in many cases regarding the rights of persons with intellectual disability (Croser, 1999; Herr, 1999). James W. Ellis, JD, a University of New Mexico Law Professor and past president of AAIDD, successfully argued before the US Supreme Court (Atkins v. Virginia, 2002) that the execution of persons with ID was cruel and unusual punishment. The Atkins v. Virginia Supreme Court ruling led to the banning of capital punishment for all persons diagnosed with ID. AAIDD was prominently mentioned in the 2002 Atkins V. Virginia Supreme Court decision as a leading national organization in defining intellectual disability (then called mental retardation). Major Activities The association offers a wide array of trainings, including an annual professional meeting. AAIDD publishes books, journals, assessment instruments, and training materials. Among its publications, AAIDD publishes two of the mostly highly cited professional journals in the field of disabilities: American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Many of its publications have been translated into dozens of languages and are disseminated and used worldwide. References & Readings Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. (2010). Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities. Retrieved January 30, 2011, from AAIDD: Http://www.aaidd.org/content_28.cfm?navID=7 Blatt, B., & Kaplan, F. (1974). Christmas in purgatory. Syracuse, NY: Human Policy Press. Croser, M. D. (1999). Federal disability legislation: 1975-1999. In R. L. Schalock, P. C. Baker, & M. D. Croser (Eds.), Embarking on a new century: Mental retardation at the end of the 20th Century (pp. 3-16). Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation. Heber, R. (1959). A manual on terminology and classification in mental retardation: A monograph supplement. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 64(2), 1-111. Herr, S. S. (1999). Presidential address 1999 - Working for justice: Responsibilities for the next millennium. Mental Retardation , 37 (5), 407-419. Nihira, K., Foster, R., Shellhaas, M., & Leland, H. (1969). AAMD Adaptive Behavior Scale. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Deficiency. 3 Schalock, R. L. (1999). Definitional Issues. In R. L. Schalock, P. C. Baker, & M. D. Croser (Eds.), Embarking on a new century: Mental retardation at the end of the 20th century (pp. 45-66). Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation. Schalock, R. L., Buntinx, W. H. E., Borthwick-Duffy, S., Bradley, V., Craig, E. M., Coulter, D. L., et al. (2010). Intellectual disability: Definition, classification, and system of supports (11e). Washington, DC: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Schalock, R. L., Buntinx, W. H. E., Borthwick-Duffy, S., Luckasson, R., Snell, M. E., Tassé, M. J., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2007). User’s Guide Mental Retardation: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports, 10th Edition. Applications for Clinicians, Educators, Disability Program Managers, and Policy Makers. Washington, DC: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Sloan, W., & Stevens, H. E. (1976). A century of concern: A history of the American Association on Mental Deficiency . Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Deficiency. Thompson, J. R., Bryant, B., Campbell, E. M., Craig, E. M., Hughes, C., Rotholz, D. et al. (2004). Supports Intensity Scale: User manual. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation. 4 View publication stats