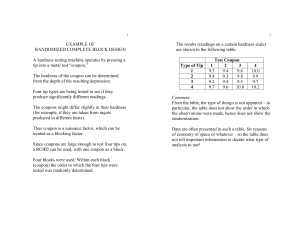

2009; 31: 322–324 TWELVE TIPS Twelve tips for blueprinting SYLVAIN CODERRE, WAYNE WOLOSCHUK & KEVIN MCLAUGHLIN Office of Undergraduate Medical Education, University of Calgary, Canada Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Professor Muhammad Luqman on 09/26/13 For personal use only. Abstract Background: Content validity is a requirement of every evaluation and is achieved when the evaluation content is congruent with the learning objectives and the learning experiences. Congruence between these three pillars of education can be facilitated by blueprinting. Aims: Here we describe an efficient process for creating a blueprint and explain how to use this tool to guide all aspects of course creation and evaluation. Conclusions: A well constructed blueprint is a valuable tool for medical educators. In addition to validating evaluation content, a blueprint can also be used to guide selection of curricular content and learning experiences. Introduction Validity is a requirement of every evaluation and implies that candidates achieving the minimum performance level have acquired the level of competence set out in the learning objectives. Typically, the type of validity that relates to measurements of academic achievement is content validity (Hopkins 1998). Evaluation content is valid when it is congruent with the objectives and learning experiences, and congruence between these pillars of education can be facilitated by using an evaluation blueprint (Bordage et al. 1995; Bridge et al. 2003). In this paper we describe an efficient and straightforward process for creating a blueprint, using examples from the University of Calgary medical school curriculum. Although its primary function is to validate evaluation content, a well constructed blueprint can also serve other functions, such as guiding the selection of learning experiences. ‘Course blueprint’ may therefore be a more appropriate descriptor of this tool. Tip 1. Tabulate curricular content The first step in blueprinting is to define and tabulate the curricular content. A blueprint template consists of a series of rows and columns. At the University of Calgary, teaching of the undergraduate curriculum is organized according to clinical presentations, so the rows in our blueprints contain the clinical presentations relevant to the course being blueprinted (Mandin et al. 1995). Column 1 in Table 1 shows the eighteen clinical presentations for the Renal Course at the University of Calgary. Curricular content can be organized in many other ways, including course themes or units. Tip 2. Provide relative weighting of curricular content Evaluations have a finite number of items, so some measure of relative weighting of content areas must be decided upon so that priority can be given to more ‘important’ areas when Correspondence: Dr Kevin McLaughlin, University Email: [email protected] 322 of Calgary, creating items. Content importance, however, is difficult to define. Attributes such as the potential harm to the patient from misdiagnosing a presentation (a measure of presentation ‘impact’), the potential for significant disease prevention (also a measure of presentation ‘impact’), and how frequently a presentation is encountered in clinical practice should be considered. At the University of Calgary we rate the impact and frequency of clinical presentations based on the criteria shown in Table 2. The impact and frequency of each clinical presentation are tabulated (columns 2 and 3 of Table 1) and then multiplied. This produces an I F product for all eighteen clinical presentations, which ranges from 1 to 9. Next, the I F product for each clinical presentation (column 4 of Table 1) is divided by the total for the I F column (80 in our example) to provide a relative weighting for each presentation, which corresponds to the proportion of evaluation items for this presentation (column 5 of Table 1). For example, hyperkalemia – a life threatening emergency that is encountered frequently by physicians caring for patients with kidney diseases – has the highest relative weighting (0.1125). But how do we know that this weighting is reliable? Tip 3. Sample opinion on weighting from all relevant groups Reliability is improved by increasing sample size and breadth (Hopkins 1998). In addition to involving course chairs and evaluation coordinators, we solicit input from teachers and, if relevant, previous learners (McLaughlin et al. 2005a). That is, weighting of a content area is established through consensus. Giving potential users the opportunity to have input into the blueprint creation may also improve the likelihood of the blueprint being used to guide all aspects of course design and evaluation (see Tip 10). Undergraduate Medical Education, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. ISSN 0142–159X print/ISSN 1466–187X online/09/040322–3 ß 2009 Informa Healthcare Ltd. DOI: 10.1080/01421590802225770 Twelve tips for blueprinting Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Professor Muhammad Luqman on 09/26/13 For personal use only. Table 1. Blueprint for the undergraduate renal course at the University of Calgary. Column #: 1 2 3 4 Presentation Impact Frequency IF Weight 2 3 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 3 2 2 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 3 3 1 3 2 2 2 6 9 4 6 4 9 6 4 6 3 4 3 6 1 3 2 2 80 0.025 0.075 0.1125 0.05 0.075 0.05 0.1125 0.075 0.05 0.075 0.0375 0.05 0.0375 0.075 0.0125 0.0375 0.025 0.025 1 Hypernatremia Hyponatremia Hyperkalemia Hypokalemia Acidosis Alkalosis ARF CRF Hematuria Proteinuria Edema Scrotal mass Urinary retention Hypertension Polyuria Renal colic Dysuria Incontinence TOTAL 5 6 7 8 9 10 Number of items Diagnosis Investigation Treatment Basic science 1.50 4.50 6.75 3.00 4.50 3.00 6.75 4.50 3.00 4.50 2.25 3.00 2.25 4.50 0.75 2.25 1.50 1.50 60 1 2 3 2 2 2 5 3 2 2 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 34 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 6 0 1 2 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 12 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 Table 2. Weighting for impact and frequency of the clinical presentations. Impact Non-urgent, little prevention potential Serious, but not immediately life threatening Life threatening emergency and/or high potential for prevention impact Tip 4. Decide on the number of items for each content area The first step in this process is deciding on the total number of evaluation items. Reliability of an evaluation is affected by both the number and discrimination of items. As a rough guide, if the average discrimination index of the items is 0.3, then approximately 50–60 items are needed to achieve reliability of 0.8. This number increases to 100 if the average item discrimination is 0.2. Reliability appears to plateau beyond 100 items (Hopkins 1998). The next step is to allocate items to content areas. This can be done by multiplying the total number of items on the evaluation by the relative weighting for each clinical presentation, and then rounding up or down to the nearest whole number. For example, a 60 item evaluation on the Renal Course should have seven items (60 0.1125) on hyperkalemia and one (60 0.0125) on polyuria (column 6 of Table 1). Weight Frequency Weight 1 2 3 Rarely seen Relatively common Very common 1 2 3 to management (Mandin 2004). The tasks for the seven items on hyperkalemia reflect this balance (columns 7–10 of Table 1). The blueprint for content validity is now complete; the next challenge is to create the valid content. Tip 6. Create evaluations based on the blueprint All evaluations used in the course – formative, summative and retake – should conform to the blueprint. The blueprint specifies the number of items needed for each clinical presentation and, within each presentation, which tasks should be evaluated. The evaluation coordinator can now create valid evaluations by following these specifications. Providing this degree of detail is also very helpful to those recruited to the task of item creation. Tip 7. Use (or create) an item bank Tip 5. Decide on the tasks for each content area There are a variety of tasks that can be evaluated within any clinical presentation, such as diagnosing the underlying cause (including specific points of history and physical examination), interpreting or selecting investigations, deciding on management and/or prevention, demonstrating basic science knowledge, etc. These tasks should be consistent with the learning objectives of the relevant course. The Medical Council of Canada identifies three key objectives for the clinical presentation of hyperkalemia – two are related to diagnosis and interpretation of lab test, and one is related Starting from scratch and creating new items for one or more evaluations can appear onerous. Using an item bank to match existing items to the blueprint reduces the burden of creating evaluations. If an item bank does not exist, the short-term investment of time and effort to create this pays off in the long run as items can then be shared between courses and even between medical schools. Tip 8. Revise learning objectives As discussed above, a blueprint provides weighting for all aspects of a course. This weighting provides an opportunity for 323 S. Coderre et al. the course chair to reflect on the learning objectives. While it may appear counterintuitive to revise learning objectives based upon a blueprint weighting, to achieve content validity the number of objectives, hours our instruction, and number of evaluation items for each clinical presentation should be proportional. Given the finite number of hours available for instruction, upon reflection it may become apparent that some learning objectives are not achievable and need to be revised. Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Professor Muhammad Luqman on 09/26/13 For personal use only. Tip 9. Revise learning experiences The weighting provided by the blueprint also offers an opportunity for reflection on learning experiences – more teaching time should be devoted to content areas with higher weighting. But this does not imply a perfect linear relationship between weighting and hours of instruction; some concepts take longer to teach than others, and the length of teaching sessions needs to be adjusted to fit into available time slots. So now, in theory, we have congruence of learning objectives, learning experiences, and evaluation. However, in order to achieve content validity, the teachers need to deliver the intended curriculum (Hafferty 1998). the intended curriculum (McLaughlin et al. 2005b). Fears that blueprint publication would improve learner performance by driving strategic learning are unsupported. In a previous study, we found that blueprint publication did not improve student performance, but significantly increased the perception of fairness of the evaluation process (McLaughlin et al. 2005c). Conclusion Blueprinting need not be onerous and we believe that the initial investment of time and effort required to create a blueprint will produce dividends over the long term. A well constructed and reliable blueprint is a valuable educational tool that can improve all aspects of course design and evaluation – benefiting both teacher and learners. After creating a reliable blueprint, content validity is achieved only when the blueprint is used to guide course design and evaluation, and is maintained through a systematic monitoring of content. Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. Tip 10. Distribute the blueprint to teachers A well constructed blueprint is a transparent outline of the intended curriculum of a course. The detail contained within a blueprint not only helps the course chair to select appropriate content area, but also helps teachers plan the learning experiences so that the content delivered is congruent with both the objectives and the evaluations. Notes on contributor DR CODERRE, MD, MSc, is an Assistant Dean of Undergraduate Medical Education at the University of Calgary. DR WOLOSCHUK, Ph.D, is a program evaluator in the Office of Undergraduate Medical Education at the University of Calgary. DR MCLAUGHLIN, MB Ch.B, Ph.D, is an Assistant Dean of Undergraduate Medical Education at the University of Calgary Tip 11. Monitor content validity When course chairs, evaluators, teachers, and learners use the same blueprint the effects of hidden curricula should be minimized (Hafferty 1998). It cannot be assumed however, that publishing a blueprint inevitably leads to its adoption – content validity still needs to be evaluated and monitored. At the University of Calgary we monitor content validity by asking students the question, ‘Did the final examination reflect the material seen and taught?’ after each summative evaluation. This allows us to evaluate and adjust the learning experiences if the students’ perception of content validity is low. Tip 12. Distribute the blueprint to learners Given the adverse consequences of academic failure in medical school, it is inevitable that evaluation drives learning. Ideally, creating and providing a blueprint to learners ensures that course leaders are ‘grabbing hold of the steering wheel’ and driving learning towards what is felt to be core course material. When a blueprint provides content validity, the effect of evaluation on learning can be embraced – rather than feared – as this tool, shown to be important in student examination preparation, reinforces the learning objectives and delivery of 324 References Bordage G, Brailovsky C, Carretier H, Page G. 1995. Content validation of key features on a national examination of clinical decision-making skills. Acad Med 70:276–281. Bridge PD, Musial J, Frank R, Roe T, Sawilowsky S. 2003. Measurement practices: Methods for developing content-valid student examinations. Med Teach 25:414–421. Hafferty FW. 1998. Beyond curricular reform: Confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med 73:403–407. Hopkins K. 1998. Educational and Psychological Measurement and Evaluation. MA, Allyn and Bacon: Needham Heights. Mandin H. 2004. Objectives for the Qualifying Examination. ON, Medical Council of Canada: Ottawa. Mandin H, Harasym P, Eagle C, Watanabe M. 1995. Developing a ‘clinical presentation’ curriculum at the university of Calgary. Acad Med 70:186–193. McLaughlin K, Lemaire J, Coderre S. 2005a. Creating a reliable and valid blueprint for the internal medicine clerkship evaluation. Med Teach 27:544–547. McLaughlin K, Coderre S, Woloschuk W, Mandin H. 2005b. Does blueprint publication affect students’ perception of validity of the evaluation process? Advan in Health Sci Educ 10:15–22. McLaughlin K, Woloschuk W, Lim TH, Coderre S, Mandin H. 2005c. The Influence of Objectives, Learning Experiences and Examination Blueprint on Medical Students’ Examination Preparation. BMC Med Educ 5:39.