Uploaded by

salsabilawind99

International Nutrition Care Process Survey: Global Evaluation Tool

advertisement

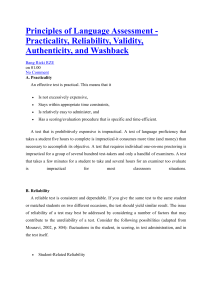

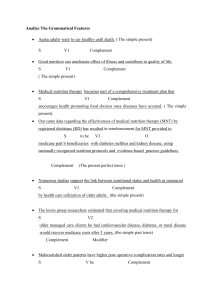

RESEARCH Original Research The International Nutrition Care Process and Terminology Implementation Survey: Towards a Global Evaluation Tool to Assess Individual Practitioner Implementation in Multiple Countries and Languages Elin Lövestam, PhD, RD*; Angela Vivanti, DHSc, AdvAPD†; Alison Steiber, PhD, RDN; Anne-Marie Boström, PhD, RN*; Amanda Devine, PhD, AN†; Orla Haughey, RD‡; Caroline M. Kiss, DCN, RD§; Nanna R. Lang, MSc; Jessica Lieffers, PhD, RDk; Lyn Lloyd, RD¶; Therese A. O’Sullivan, PhD, APD*; Constantina Papoutsakis, PhD, RD; Lene Thoresen, PhD, RD#; Ylva Orrevall, PhD, RD*; on behalf of the INIS Consortium ARTICLE INFORMATION Article history: Submitted 18 August 2017 Accepted 4 September 2018 Keywords: Nutrition Care Process and Terminology Implementation Evaluation Validation Survey Supplementary materials: Figure 2 is available at www.jandonline.org 2212-2672/Copyright ª 2018 by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.09.004 * Certified in Sweden. Certified in Australia as an Accredited Practicing Dietitian (APD), Accredited Nutritionist (AN), or Advanced Accredited Practicing Dietitian (AdvAPD). ‡ Certified in Ireland. § Certified in Switzerland. k Certified in Canada. ¶ Certified in New Zealand. # Certified in Norway. † ABSTRACT Background The Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and NCP Terminology (NCPT) is a systematic framework for critical thinking, decision making, and communication for dietetics practitioners worldwide, aiming to improve quality and patient safety in nutrition care. Although dietetics practitioners in several countries have implemented the NCP/NCPT during recent years, to date there is no globally validated instrument for the evaluation of NCP/NCPT implementation that is available in different languages and applicable across cultures and countries. Objective The aim of this study was to develop and test a survey instrument in several languages to capture information at different stages of NCP/NCPT implementation across countries and cultures. Setting In this collaboration between dietetics practitioners and researchers from 10 countries, an International NCP/NCPT Implementation Survey tool was developed and tested in a multistep process, building on the experiences from previous surveys. The tool was translated from English into six other languages. It includes four modules and describes demographic information, NCP/NCPT implementation, and related attitudes and knowledge. Methods The survey was reviewed by 42 experts across 10 countries to assess content validity and clarity. After this, 30 dietetics practitioners participated in cognitive interviews while completing the survey. A pilot study was performed with 210 participants, of whom 40 completed the survey twice within a 2- to 3-week interval. Results Scale content validity index average was 0.98 and question clarity index was 0.8 to 1.0. Cognitive interviews and comments from experts led to further clarifications of the survey. The repeated pilot test resulted in Krippendorff’s a¼.75. Subsequently, refinements of the survey were made based on comments submitted by the pilot survey participants. Conclusions The International NCP/NCPT Implementation Survey tool demonstrated excellent content validity and high testeretest reliability in seven different languages and across an international context. This tool will be valuable in future research and evaluation of implementation strategies. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;-:---. O VER THE PAST SEVERAL YEARS, THE NUTRITION Care Process (NCP) and the associated Nutrition Care Process Terminology (NCPT) have been introduced and subsequently implemented in several countries around the world.1-3 The NCP/NCPT was developed by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (previously known as the American Dietetic Association), to provide dietetics practitioners with a framework for ª 2018 by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. decision making and critical thinking in nutrition care.4,5 The NCP also provides a structure for systematic evaluation of outcomes, which can be used to demonstrate the effectiveness of dietetics practice as well as in dietetics research.6 The standardized NCPT was developed to support dietetics practitioners in clinical documentation, dietetics-related communication, outcomes management, and research.7 In turn, both the NCP and NCPT are expected JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 1 RESEARCH to enhance person-centeredness and patient safety as well as the overall quality of nutrition care. International interest in the NCP and NCPT has grown during recent years, and several dietetics associations and other organizations, such as federations of associations, have openly acknowledged and supported the importance of adopting NCP/NCPT.8-11 The NCP/NCPT is currently being implemented in a number of different countries globally, and to date, different editions of the NCPT have been translated into 11 languages and dialects.1 Studies from the United States, Australia, and Sweden show that dietetics practitioners report many benefits with NCP/ NCPT implementation.12-14 These benefits include the provision of support and a framework for critical thinking in nutrition care, improved clarity in communication and clinical documentation, and an increased acknowledgement of dietetics practitioners’ unique competence among other health care professionals.12-14 There is paucity of data on the barriers of NCP/NCPT implementation in different practice settings. Time limitations, lack of incorporation of the NCPT within electronic health records, and lack of suitability for all areas of practice are some previously identified barriers.12,15 Because the NCP/ NCPT is designed to be used globally, it is important to be able to directly compare across countries and determine whether any global strategies are required to promote adoption. A key challenge in studying NCP/NCPT implementation is the lack of a uniform and validated instrument that can be used globally to measure and evaluate degree of use among individual dietitians in different countries, perceived barriers to use, and potential benefits. In 2012 researchers in the United States developed an audit tool to be used for evaluating nutrition care documentation in a clinical setting.16 The tool was further developed and tested in Sweden in 2015.17 These audit instruments assess whether key components of the NCP are documented in patient records; however, they do not collect any information on NCP/NCPT use and experiences among dietetics practitioners. Over the past several years, dietetics associations and association federations around the world have evaluated NCP/ NCPT implementation through similar surveys.18-21 These instruments have primarily focused on preimplementation prerequisites, or individual dietitians’ experiences at early implementation stages.22 This is to be expected because when these studies were conducted, implementation was in its beginning stages. Of note, the surveys used have not been tested at an international level. The results from these surveys have mostly been used for national professional development purposes. Only the results from the Australian surveys have been published in peer-reviewed international journals.12,23-25 The Australian Attitudes Support Knowledge NCP (ASK-NCP) survey was developed in 2015 to assess the expectations and experiences of pre- and early post-NCP implementers, and has been validated in an Australian context.22 Since these earlier surveys were developed and used, more countries have progressed in their NCP/NCPT implementation. Thus, there is a need to design and evaluate an instrument to survey all implementation stages, so that enablers and barriers to progressing through later stages can be investigated. An international, uniform, and validated instrument would be a valuable tool for dietetics practitioners and organizations 2 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS RESEARCH SNAPSHOT Research Question: What is the content validity and reliability of a questionnaire developed to capture different stages of Nutrition Care Process and Terminology implementation across countries and cultures? Key Findings: A survey tool was developed based on earlier national instruments. The multistep testing process included 42 expert assessments resulting in a scale content validity index average of .98, 30 cognitive interviews resulting in qualitative comments and further refinements of the tool, and a pilot study with 210 participants, of whom 40 participated in a testeretest survey showing Krippendorff’s a¼.75. interested in understanding NCP/NCPT implementation. Such an instrument would allow this process to be studied over time and compared between countries.21-24 Building and expanding on previous work, the aim of this study was to develop and test a survey tool to capture information from individual dietitians in different countries on different stages of NCP/NCPT implementation for global application in a range of languages. METHODS The development and testing of this survey tool employed a multistep process, which is illustrated in Figure 1.26-30 The study was coordinated from Sweden (E. L.), with initial planning and design discussions between representatives from Australia, Canada, Sweden, and the United States. January 2016 1. DraŌing of survey Based on earlier experiences and quesƟonnaires 2. TranslaƟon Danish, French (Canadian), German (Swiss), Greek, Norwegian, Swedish 3. Expert content validaƟon followed by revision 5 experts in each country (n=50) Expert content validaƟon performed twice 4. CogniƟve interviews followed by revision 3 dieƟƟans in each country (n=30) 5. Pilot study followed by revision 20-25 dieƟƟans in each country (n=250) January 2017 6. Final version and translaƟon quality check QualitaƟve translaƟon review Figure 1. Development and testing process of the International Nutrition Care Process and Terminology Implementation Survey. -- 2018 Volume - Number - RESEARCH However, as the purpose of the study was to develop an international survey tool for use in several countries with different languages, representatives from a range of countries were also invited to participate. Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, and Switzerland were invited initially because they had been involved in NCP/NCPT collaborations with one or more of the members of the core research group (E. L., A. V., A. S., Y. O.). Representatives from Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, and the United States all assisted in drafting the first version of the survey. After the first version of the survey tool was drafted, a representative from Greece was also included. The first author (E. L.) coordinated the study and developed the study design in dialogue with the core research group (E. L., A. V., A. S., Y. O.) and the representatives from each participating country. The survey tool was based on earlier experiences from Australian, Canadian, Swedish, and US NCP/NCPT surveys.18,21,22,31-33 As previously stated, most of the questions in the earlier surveys were developed to study implementation prerequisites before or at an early stage of NCP/NCPT implementation. In the initial discussions, survey questions were collected from the Canadian Alberta Health Services Survey (personal communication with Carlota BasualdoHammond, December 22, 2016) and the Australian ASK-NCP survey.22 Also, several questions from these surveys originated from earlier US surveys and evaluation initiatives.31-33 Questions from the NCP Orientation Tutorial Quiz34 were also collected. These survey questions were subsequently modified and new questions were developed, with respect to the current implementation stage in the 10 participating countries, the 2015 version of NCP and NCPT, and the questions’ applicability across countries. To accommodate different stages and degrees of NCPT implementation, it was decided to develop a series of separate survey modules with slightly different aims, instead of one survey that included all questions. This approach allowed countries to use selected survey modules based on their needs and stage of NCP/NCPT implementation. For example, focusing on NCP but not NCPT, or studying knowledge but not attitudes. Table 1 shows the content and aim of each module and the original source of each of the questions in the final survey. All modules were tested in all the participating countries with the exception of Module 4 (NCP/NCPT knowledge) that was not used by Denmark and Sweden. The first draft of the survey tool was developed in English. The survey was then translated into Danish, French (Canadian and Swiss), German (Swiss), Greek, Norwegian, and Swedish. A translator was chosen by the responsible researcher in each country, with the criterion that he or she should have excellent knowledge of both English and the local language of interest. When applicable, terms and definitions from the official NCPT translations (which are available for subscribers on www.ncpro.org) were used. To assess the content validity and reliability of the survey tool and to refine content and wording, a multistep testing process took place that included an expert content validation, cognitive interviews, and pilot testing (see Figure 1). The translations were also refined after each step in this process. Only registered or accredited dietitians (based on the licensure regulations in each included country) were invited -- 2018 Volume - Number - to participate in the testing process. For all three steps in this process, the selection of participants was representative of a variety of perspectives, such as geographical location, education level, and dietetics practice setting. Expert Content Validation The first step of the testing process involved having five experts from each of the 10 participating countries assess the survey for content validity and clarity.35 Inclusion criteria for the experts were: familiarity with the NCP/NCPT; recent experience in clinical or academic dietetics work involving NCP/NCPT use (ie, during the last year); and bachelor’s degree education level as a minimum. For the translated versions, the five experts were required to be proficient in both English and the local language, as they also assessed the quality of the translation.36 All experts received detailed written instructions on how to perform the assessment. The experts had the choice to complete their assessment via an online format (using the Swedish software Kurt, Uppsala University, 2016), or a word processing software file that could be emailed to the researchers. In countries with more than one official language (Canada and Switzerland), at least two experts assessed the survey in each language. In Canada, in addition to this, two bilingual experts assessed two versions of the survey: both the English and French. Experts volunteered their time and no payment was given. Experts were asked to independently rate each survey question and the possible response options in relation to the module’s aim (see Table 1) and its clarity on a scale ranging from one to four. (1¼Not relevant/Not clear, 2¼Somewhat relevant/Somewhat clear, 3¼Quite relevant/Quite clear, and 4¼Highly relevant/Very clear). Questions with ratings of three or four were considered to be of appropriate quality.35 The content validity index (CVI) was calculated for each question as well as for the whole survey tool (S-CVI). For each participating country, CVI was also calculated for each of the four survey modules. S-CVI-Universal Agreement can be defined as the proportion of survey questions rated three or four by all experts. The S-CVI-Average is an alternative measure that is calculated in two steps. First, for each survey question, the proportion of experts who rated the question as three or four is determined. Second, these proportions are then averaged to determine the average proportion of survey questions rated as three or four across the various experts.37 For S-CVI-Universal Agreement, the recommended standard is 0.8, and for S-CVI-Average it is 0.9. Using the S-CVI-Universal Agreement in a test including more than five to 10 experts will imply a risk of falsely low results, which is why the S-CVI-Average is recommended when using large samples of experts.37 Therefore, in this study, both S-CVI-Universal Agreement and S-CVI-Average were calculated. Clarity and translation quality were assessed in the same way, so a Q-clarity index and Q-translation quality index was determined for each question. The expert content validation was performed twice. All experts from the first round of expert content validation were invited to review the survey a second time with revisions JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 3 RESEARCH Table 1. Modules and origin of questions in the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey Module Aim Origin of questions Module 1: Demographic information To assess background information about the respondents. This can be compared with data from national dietetic associations to assess the representativeness of the respondents 1-3 Module 2: 6 AHS, validated in ASK NCPc21 Part A: NCP/NCPT implementation 8, 13-17 Originally developed for INIS Part B: NCP implementation 10 ASK NCP22 Part C: NCPT implementation 11, 12, 18, 19 AHS, validated in ASK NCP22 Adapted to later implementation stages in INIS 20 a-g, i-k AHSd validated in ASK NCP22 Originally developed for INIS Module 3: NCP/NCPT attitudes Module 4: NCP/NCPT knowledge To assess implementation level of NCP/NCPT 4-5, 7 Originally developed for the INISa AHSb To assess to which degree dietitians see benefits with the NCP/NCPT regarding aspects such as communication, the dietetics professional’s role, thinking processes, nutrition care quality, and patient-centered care To assess the level of knowledge concerning NCP/NCPT, especially concerning the Nutrition Diagnosis step 20 h, l-p 21-28 Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics tutorial questions validated in ASK NCP22,34 a INIS¼International Nutrition Care Process and Terminology Implementation Survey. AHS¼Alberta Health Services Survey. c ASK NCP¼Attitudes Skill Knowledge NCP Survey. d Adapted from references 31 and 32. b taking place between the two assessments. During the revision, all questions with a S-CVI-Average <0.8 were changed. Based on the reviewers’ comments, some of the questions with S-CVI-Average <0.8 were removed because a majority of reviewers found them redundant, whereas other questions were added.35 This part of the survey testing started in June 2016 and was finished in August 2017. Cognitive Interviews In the next step of the testing process, cognitive interviews were carried out, which involved interviewing three dietetics practitioners in each country while they were completing the survey.29 In countries with more than one official language, one to three interviews in each language were conducted. The interviews were conducted in person, by telephone or online (eg, Skype; Microsoft Corporation). Inclusion criteria for the interviewees were: 4 no prior participation during the expert content validation step; familiarity with NCP/NCPT; and at least 1 year of experience in clinical dietetics. JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS In accordance with cognitive interview recommendations, probing questions were asked while completing the survey to identify any ambiguities.29,38 The interviews were completed by the responsible researchers from each country, who all had participated in the survey development process. All interviewers received detailed instructions on how to conduct the interviews, which included suggested interview questions. Each interview lasted for approximately 1 hour and included between two and four of the survey modules. In each country, each of the four modules had to be included in at least one of the interviews, except for Denmark and Sweden, where only Modules 1 to 3 were included in the testing. Results (including any ambiguities as well as all suggestions for improved clarity) were documented on a standardized report form that was returned to the study coordinator (E. L.).38 All reports were carefully summarized. Based on results from the interviews, further revisions were made to improve the content and clarity of the survey. Revisions were also made to improve the translation of the survey. This part of the survey testing was performed during September and October 2016. -- 2018 Volume - Number - RESEARCH Pilot Study In the final testing step, an online pilot survey was disseminated to 20 to 25 dietetics practitioners in each of the 10 countries, using the web-based tool SurveyMonkey (www. surveymonkey.com). The number of participants in the pilot study was chosen based on the need for sufficient participants to allow for any necessary analyses on the collected data,27 while at the same time supporting achievable recruitment in countries with smaller numbers of dietetics practitioners, including Switzerland and Norway. For the countries with more than one official language, the number of participants completing the survey in each language ranged from five to 17. Inclusion criteria for participating in the pilot study were no prior participation as experts or interviewees during the earlier testing steps, and recent dietetics-related work experience (ie, during the past year). The pilot survey included comment boxes after each question, and participants were asked to document any aspect that was ambiguous or unclear in these boxes. Of the 20 participants in each country, five were asked to complete the survey twice, 2 to 3 weeks apart.26,27 To allow comparison between the two occasions, the identity of these participants was confirmed using a self-generated code.39 For testeretest participants, the first survey was open from October 20 to 27, 2016, and the second survey was open from November 10 to 17, 2016. For the other participants completing the survey once, it was open from October 20 to November 17, 2016. The results of the pilot study were analyzed in four ways by the study coordinator: All comments were qualitatively analyzed and summarized. All skipped questions were identified to determine whether any questions seemed difficult to understand or answer. For Module 3, focusing on NCP/NCPT attitudes, an explorative factor analysis with Varimax rotation was performed to identify any underlying subscales and themes in that module.27,40 For participants who completed the survey twice, Krippendorff’s a was calculated to assess the testeretest reliability of the survey, both for the international sample and for each participating country.41 In this measurement, 1.0 means perfect reliability, whereas .0 means absence of reliability. There is no standardized criteria, but a¼.67 is often set as an acceptable level of agreement.41 Based on the results from the pilot study, minor revisions were made for questions with a Krippendorff’s a<.67, and the survey tool was finalized. After this, a final translation review was conducted. This was done by experts who were fluent in both English and the local language. In most cases they reviewed the translation in dialogue with both the translator and responsible researcher from each country until agreement was reached concerning the translation of each question.36 Ethical Considerations This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Medical Sciences in Uppsala, Sweden. The Canadian portion of this study also received specific ethical approval -- 2018 Volume - Number - from the University of Waterloo Office of Research Ethics, ORE: 21558. All participants were informed about the purpose and design of the study and provided oral or written consent to participate. RESULTS The final product of the study, the International NCP/NCPT Implementation Survey (INIS) tool, is found in Figure 2 (available at www.jandonline.org). It consists of four main modules: demographic information, NCP/NCPT implementation, NCP/NCPT attitudes, and NCP/NCPT knowledge. Summary results of the three-step survey testing are shown in Table 2 and the main results are described below. Expert Content Validation In total, 42 experts rated the content validity and clarity of the survey twice. After the second review, the S-CVI-Average was 0.98, and S-CVI-Universal Agreement was 0.84. CVI for each question ranged from 0.93 to 1.0, whereas Q-clarity index ranged between 0.8 and 1.0 (Table 2). For each separate country, S-CVI-Average ranged from 0.95 to 1.0, the S-CVIUniversal Agreement ranged from 0.77 to 1.0 and the S-clarity index ranged from 0.91 to 0.99 (see Table 3). For the translated versions of the survey tool, translation quality index ranged from 0.93 to 0.99, as shown in Table 3. Cognitive Interviews In total, 30 cognitive interviews were conducted. Most of the feedback received was on question wording and definition of concepts, such as “NCP,” “NCPT,” “education,” and “interprofessional.” Several suggestions were received to help increase clarity of questions. Also the visual design of questions (eg, matrix questions) as well as the order of questions was evaluated. In Module 1 (demographic information), some country-specific response options were added, to reflect various educational qualifications and health care systems, which vary internationally, and definitions for areas of dietetics practice. Pilot Study In total, 210 dietetics practitioners (out of w250 invited) across the 10 countries participated in the pilot study. Of these, 40 dietetics practitioners (out of 50 invited) completed the survey twice for the testeretest analysis. Table 4 shows demographic details of the pilot study participants. Comments received during the pilot study were mainly focused on question wording or the need for additional country-specific response options. Some questions were perceived as too time-consuming. Of the 210 pilot participants, 18 (8%) did not complete the survey. Of these 18 participants, two provided comments about the survey questions but did not answer the questions; five participants left the survey during Module 1 (demographic information); another 10 participants left during Module 2 (NCP/NCPT implementation); and one left just before Module 3 (NCP/NCPT attitudes). Among the participants who completed the survey, questions 20 l to 20 p stood out as being skipped most often (Table 2). After the pilot test, a “not applicable” response option was added to these JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 5 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS Step 1. Expert Content Validation (n[42) Step 2. Cognitive Interviews (n[30) Step 3. Pilot Study (n[210) Testeretest Krippendorff’s a (95% CI)c (n[45) Factor analysis Testeretest % agreement result (only Module 3) (n[45) 0 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) 100 Wording, applicability Adaption to country specific of response options needs in different countries 4 ed 0.93 Adaption to Applicability of country specific response options in needs different countries 5 .92 (.80 to 1.00) 93 0.98 0.93 None Applicability of response options in different countries 10 .98 (.93 to .99) 88 5. Area of practice 1.00 0.98 Wording Need to be able to choose more than 1 response option 11 .71 (.53 to .87) 91 All Module 1 0.97 (average) 0.93 (average) Not applicable Not applicable .90 (.88 to.93) 93 1.00 1.00 Definition of concepts Wording 9 7. Where learned about NCP 1.00 0.93 Wording, definitions of concepts None 9 8. Who organized NCP education 1.00 Wording, additional response options Additional response options Content validity indexa Clarity indexb Main focus of comments Main focus of comments 1.00 1.00 Wording, additional response options None 2. Registered dietitian or not 0.90 0.80 3. Level of education 0.98 4. When education was completed Question No. not completed Module 1: Demographic information 1. Country of residence Not applicable 93 Module 2: NCP/NCPT implementation 6. Heard of NCP or not -- 2018 Volume 0.98 0 (n¼126) ed 100 .69 (.50 to .85) 87 .60 (.42 to.76) 85 - Number (continued on next page) RESEARCH 6 Table 2. Main results of the 3-step testing of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey - -- Table 2. Main results of the 3-step testing of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey (continued) 2018 Volume Step 1. Expert Content Validation (n[42) Step 2. Cognitive Interviews (n[30) Step 3. Pilot Study (n[210) - Number Testeretest Krippendorff’s a (95% CI)c (n[45) Factor analysis Testeretest % agreement result (only Module 3) (n[45) Content validity indexa Clarity indexb Main focus of comments Main focus of comments 9. Aspects with positive influence 1.00 0.98 Wording and structure, clarity of scale, lack of “not applicable” option Split question into 11 2 parts to avoid ambiguity .71 (.64 to .78) 61 10. Aspects with negative influence 1.00 0.98 Wording and structure, clarity of scale, lack of “not applicable” option Split question into 15 2 parts to avoid ambiguity .80 (.74 to .85) 65 11. To what extent is NCP used 1.00 0.95 Wording, definition of Layout and design 16 concepts of matrix .77 (.71 to .83) 65 12. Used NCP for how long 1.00 1.00 Wording, definition of Layout and design 16 concepts of matrix .89 (.84 to .94) 85 13. Documentation of goals 0.95 0.93 Definition of concepts Wording 14 .72 (.47 to .89) 65 14. Documentation of outcomes 0.97 0.97 Definition of concepts Wording 16 .71 (.59 to .83) 51 15. Workplace expect documentation of outcomes 1.00 0.98 Definition of concepts None 15 .51 (.28 to .73) 68 16. NCPT access 1.00 1.00 Wording None 10 .76 (.58 to .90) 83 17. NCPT language 0.95 0.95 Wording, additional response options Allow more than one response option 0 (n¼85) .92 (.76 to 1.00) 94 18. To what extent is NCPT used 1.00 0.97 Wording, definition of Layout and design 16 concepts of matrix .80 (.75 to .86) 57 19. Used NCPT for how long 1.00 0.97 Wording, definition of Layout and design 17 concepts of matrix .85 (.77 to .91) 80 All Module 2 0.97 (average) Not applicable 0.68 (.64 to .71) 74 Question No. not completed - Not applicable Not applicable (continued on next page) 7 RESEARCH JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 0.99 (average) JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS Step 1. Expert Content Validation (n[42) Step 2. Cognitive Interviews (n[30) Step 3. Pilot Study (n[210) Testeretest Krippendorff’s a (95% CI)c (n[45) Factor analysis Testeretest % agreement result (only Module 3) (n[45) -- 2018 Volume - Number Content validity indexa Clarity indexb Main focus of comments Main focus of comments 20 a) Benefits with NCP 1.00 0.98 Wording, lack of “not applicable” option Add comment box 16 .49 (.15 to .79) 78 Factor 1 20 b) Benefits with NCPT 1.00 0.97 Wording, lack of “not applicable” option Add comment box 18 .85 (.70 to .96) 90 Factor 1 20 c) Clearer documentation 0.98 0.95 Add comment box 16 .75 (.57 to .92) 83 Factor 1 20 d) Valued in interprofessional teams 1.00 0.90 Definition of concepts Add comment box 16 .79 (.67 to .90) 60 Factor 1 20 e) Provide structure and framework 1.00 1.00 Add comment box 16 .67 (.42 to .88) 78 Factor 1 20 f) Provide common vocabulary 1.00 1.00 Add comment box 18 .53 (.27 to .75) 68 Factor 1 20 g) Facilitate transfer to other settings 0.98 0.95 Add comment box 18 .64 (.44 to .81) 63 Factor 1 20 h) Facilitate communication between dietitians 0.98 0.95 Add comment box 18 .74 (.60 to .88) 70 Factor 1 20 i) Facilitate communication with health care professionals 0.98 1.00 Add comment box 18 .81 (.69 to .91) 65 Factor 1 20 j) Improve nutrition care 1.00 1.00 Add comment box 18 .81 (.66 to .92) 73 Factor 1 20 k) Encourage critical thinking 0.98 1.00 Definition of concepts Add comment box 18 .64 (.39 to .84) 63 Factor 1 20 l) Facilitate patient involvement 1.00 1.00 Wording Add comment box 21 .82 (.72 to .91) 68 Factor 2 20 m) Allow for holistic perspective 0.93 0.93 Wording Add comment box 21 .68 (.38 to .86) 60 Factor 2 Question No. not completed Module 3: NCP/NCPT attitudes Wording Wording - (continued on next page) RESEARCH 8 Table 2. Main results of the 3-step testing of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey (continued) -- Table 2. Main results of the 3-step testing of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey (continued) 2018 Volume Step 1. Expert Content Validation (n[42) Step 2. Cognitive Interviews (n[30) Step 3. Pilot Study (n[210) - Number Testeretest Krippendorff’s a (95% CI)c (n[45) Factor analysis Testeretest % agreement result (only Module 3) (n[45) Content validity indexa Clarity indexb Main focus of comments Main focus of comments 20 n) Help with internship training 1.00 1.00 Lack of “not applicable” option Add comment box 22 .69 (.38 to .86) 70 Factor 2 20 o) Support research 0.97 1.00 Wording, lack of “not applicable” option Add comment box 21 .72 (.56 to .86) 60 Factor 2 20 p) Support evaluation and development 0.95 0.98 Definition of concept Add comment box 22 .72 (.52 to .87) 70 Factor 2 All Module 3 0.98 (average) 0.98 (average) Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable .77 (.71 to .82) 70 21. What is the first step 0.96 0.98 Wording None 17 (n¼172) .74 (.49 to 1.00) 90 Question No. not completed - Module 4: NCP/NCPT knowledge 0.97 0.97 Wording Spelling 17 (n¼172) 0.89 0.96 Wording None 17 (n¼172) 1.00 (.00 to 1.00) 100 24. Which term for insufficient intake 0.97 0.97 Wording None 18 (n¼172) .69 (.07 to 1.00) 93 25. Which are the domains of nutrition diagnosis 0.96 0.96 Wording Wording 17 (n¼172) .68 (.27 to 1.00) 90 26. Which are the connectors in PESe statement 0.96 0.96 Wording None 17 (n¼172) .72 (.30 to 1.00) 93 27. Diagnostic term where in 0.96 PES statement 0.95 Wording None 16 (n¼172) .80 (.51 to 1.00) 93 28. Laboratory values where 0.98 in PES statement 0.93 Wording Wording 17 (n¼172) .75 (.50 to 1.00) 90 29. General comments (open question) 0.98 None None Not applicable 0.98 .66 (e.02 to 1.00) Not applicable 97 Not applicable (continued on next page) 9 RESEARCH JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 22. Etiology in which step 23. Which is not a nutrition diagnosis 10 77 c b a The proportion of experts considering the question to be relevant for the survey’s purpose. Content validity index >0.8 is considered acceptable content validity. The proportion of experts considering the question to be clearly formulated and easily understood. Clarity index >0.8 is considered acceptable clarity. Krippendorff’s a>.67 is considered acceptable reliability. d Krippendorff’s alpha not applicable due to too small variety in responses. e PES¼problem, etiology, signs, and symptoms (nutrition diagnosis statement). .72 (.70 to .74) Not applicable 0.98 (average) Overall survey 0.84 (average) Not applicable Not applicable 93 .91 (.87 to .95) Not applicable 0.96 (average) All Module 4 Question 0.96 (average) Not applicable No. not completed Main focus of comments Clarity indexb Main focus of comments Not applicable Factor analysis Testeretest % agreement result (only Module 3) (n[45) Testeretest Krippendorff’s a (95% CI)c (n[45) Content validity indexa Step 3. Pilot Study (n[210) Step 2. Cognitive Interviews (n[30) Step 1. Expert Content Validation (n[42) Table 2. Main results of the 3-step testing of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey (continued) RESEARCH JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS questions to avoid survey incompletion and question skipping. The testeretest analysis that was applied to assess intrarater reliability showed a mean Krippendorff’s a¼.75. For separate questions, all except seven showed an a>.67. For questions with results <.67, comment fields or “not applicable” or “I don’t know” response options were added to increase the suitability of response options for participants. Two questions (Q2 and Q6) were not included in the reliability test because the responses were very uniform, which does not fit with the Krippendorff’s a test as this test requires a certain degree of variation in the data. A separate reliability analysis was done for each participating country regarding each of the four modules, where a majority of the results showed Krippendorff’s a scores ranging from .82-1.00 for Modules 1 (demographic information), 2 (NCP/NCPT implementation) and 4 (NCP/NCPT knowledge), as shown in Table 5. For Module 3 (NCP/NCPT attitudes), Krippendorff’s a scores were slightly lower (range¼.48 to .75). Therefore, comment fields and “not applicable” response options were added in this module in the final version of the survey tool. In the Greek context, testeretest reliability regarding Module 2 (NCP/NCPT implementation) and Module 4 (NCP/NCPT knowledge) showed lower reliability compared with the other countries (see Table 5). Looking at the actual responses on Module 4, all countries but Greece and Norway had a proportion of 84% to 90% correct answers on this module, whereas Greece and Norway had a proportion of 39% and 53%, respectively. For Module 3 (NCP/NCPT attitudes), the exploratory factor analysis suggested that data might fit in a two-factor model (Table 2). However, this could not be confirmed in a subsequent confirmatory factor analysis because mode of fit was not acceptable for this dataset. The exploratory factor analysis did not result in any changes in the survey. DISCUSSION To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale multinational development and evaluation of a measurement tool focused on dietetics practice from an individual practitioner perspective. The INIS tool was developed to provide the global dietetics profession with an internationally applicable survey tool to measure and evaluate NCP/NCPT implementation. This comprehensive study demonstrates that the INIS tool has both acceptable content validity and reliability across 10 countries in seven different languages. Previously, locally and nationally tested tools have been published in peer-review journals.17,22 However, no other international development projects of this magnitude have previously been undertaken in the field of dietetics—this study included more than 20 researchers and 200 dietetics practitioners from 10 countries. Findings not only confirm the usefulness of the INIS tool, but also provide valuable insights into multinational dietetics research collaboration. In this study, a large group of dietetics practitioners and researchers from 10 countries has agreed on what they find to be the most important aspects to evaluate when measuring NCP/ NCPT implementation. Nevertheless, several cultural differences were also discovered. The need for adjustment to country-specific circumstances was especially seen in the demographic information module, where adaptations to -- 2018 Volume - Number - -- 2018 Volume Table 3. Country-specific content validity index of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey (INIS), after second expert content validation round - Question Australia Canadaa (n[4) (n[3) Denmark (n[4) Greece (n[3) New Ireland Zealand (n[5) (n[4) Norway (n[5) Sweden (n[5) Switzerlanda (n[4) United States (n[5) Number content validity indexb ! - Module 1: Demographic information 1. Country of residence 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 2. Registered dietitian or not 0.67 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 0.75 1.0 1.0 0.67 1.0 3. Level of education 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 4. When education was completed 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.75 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 5. Area of practice 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 Average modular content validity index 0.93 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.92 0.9 1.0 1.0 0.93 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 Module 2: NCP/NCPT implementation 6. Heard of NCP or not 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 8. Who organized NCP education 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 9. Aspects with positive influence 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 10. Aspects with negative influence 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.75 0.80 1.0 1.0 1.0 11. To what extent is NCP used 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 12. Used NCP for how long 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 13. Documentation of goals 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 14. Documentation of outcomes 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 15. Workplace expects documentation of outcomes 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 16. NCPT access 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 17. NCPT language 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.75 1.0 18. To what extent is NCPT used 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 19. Used NCPT for how long 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 Average modular content validity index 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.98 0.99 1.0 0.98 0.99 (continued on next page) 11 RESEARCH JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 7. Where learned about NCP JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS Question Australia Canadaa (n[3) (n[4) Denmark (n[4) Greece (n[3) New Ireland Zealand (n[5) (n[4) Norway (n[5) Sweden (n[5) Switzerlanda (n[4) United States (n[5) content validity indexb ! Module 3: NCP/NCPT attitudes 20 a) Benefits with NCP 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 b) Benefits with NCPT 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 c) Clearer documentation 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 20 d) Valued in interprofessional teams 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 e) Provide structure and framework 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 f) Provide common vocabulary 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 g) Facilitate transfer to other settings 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 h) Facilitate communication between dietitians 0.67 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 i) Facilitate communication with health care professionals 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 -- 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 20 l) Facilitate patient involvement 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 m) Allow for holistic perspective 0.67 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.8 1.0 1.0 0.8 20 n) Help with internship training 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 o) Support research 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.75 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20 p) Support evaluation and development 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.6 Average modular content validity index 0.96 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.98 0.98 1.0 1.0 0.8 1.0 1.0 N/Ac 1.0 1.0 0.75 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 22. Etiology in which step 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 N/A 0.67 1.0 23. Which is not a nutrition diagnosis 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 0.83 0.75 1.0 N/A 1.0 0.75 24. Which term for insufficient intake 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 N/A 0.67 1.0 Number Module 4: NCP/NCPT knowledge - 1.0 20 k) Encourage critical thinking 2018 Volume 20 j) Improve nutrition care 21. What is the first step - (continued on next page) RESEARCH 12 Table 3. Country-specific content validity index of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey (INIS), after second expert content validation round (continued) -- 2018 Volume Table 3. Country-specific content validity index of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey (INIS), after second expert content validation round (continued) - Question Australia Canadaa (n[3) (n[4) Denmark (n[4) Greece (n[3) New Ireland Zealand (n[5) (n[4) Norway (n[5) Sweden (n[5) Switzerlanda (n[4) United States (n[5) Number ! content validity indexb - 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 0.75 26. Which are the connectors in PES statementd 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 0.75 27. Diagnostic term where in PES statement 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 28. Laboratory values where in PES statement 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 1.0 29. General comments (open question) 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 Average modular content validity index 1.0 1.0 N/A 1.0 0.98 0.94 1.0 N/A 0.93 0.92 Average content validity index 0.98 1.0 1.0 1.00 0.98 0.96 0.99 1.00 0.97 0.95 Universal agreement content validity index 0.89 0.96 0.93 1.00 0.98 0.96 0.98 1.00 0.91 0.77 Average clarity indexe 0.93 0.91 0.97 0.99 0.99 0.96 0.97 0.98 0.96 0.93 Average translation quality indexf (language) N/A 0.93 (French) 0.97 (Danish) 0.99 (Greek) N/A N/A 0.95 (Norwegian) 0.98 (Swedish) 0.93 (French) 0.99 (German) N/A All instruments a In Canada and Switzerland, INIS was validated in multiple languages (French/English and French/German). The results presented in Table 3 summarize the results from the multiple languages in these countries. Content validity index is the proportion of experts considering the question to be relevant for the survey’s purpose. Content validity index >0.8 is considered acceptable content validity. N/A¼not applicable. d PES¼problem, etiology, signs, and symptoms (nutrition diagnosis statement). e Clarity index is here defined as the proportion of experts considering the question to be clearly formulated and easily understood. Clarity index >0.8 is considered acceptable clarity. f The proportion of experts agreeing with the translation. Translation quality index >0.8 is considered acceptable translation quality. b c 13 RESEARCH JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 25. Which are the domains of nutrition 1.0 diagnosis JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS Level of education Total (n[213) Australia (n[23) Canada (n[22) Denmark (n[20) Greece (n[18) Ireland (n[24) New Zealand (n[22) Norway (n[24) Sweden (n[23) Switzerland (n[11) United States (n[26) (n¼207) (n¼22) (n¼21) (n¼19) (n¼17) (n¼24) (n¼21) (n¼24) (n¼23) (n¼11) (n¼25) Bachelor’s degree 99 8 13 14 8 21 3 0 14 8 10 Master’s degree 92 12 7 1 9 2 17 20 9 1 14 6 1 1 0 0 1 0 2 0 0 1 10 1 0 4 0 0 1 2 0 2 0 Doctoral degree Other Area of practice (possible to select more than 1 option) (n¼200) (n¼23) Patient relatedeinpatients 129 15 Patient relatedeoutpatients (n¼19) (n¼18) (n¼17) (n¼23) (¼21) (n¼24) (n¼23) (n¼11) (n¼21) 9 15 13 22 13 13 17 9 3 13 108 13 9 12 0 15 15 15 10 6 Teaching 27 2 4 6 5 2 3 3 0 0 2 Research 30 4 4 1 10 1 2 2 1 2 3 Community 12 1 3 4 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 9 0 1 1 4 0 1 1 1 0 0 Foodservice 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Management 13 4 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 Consultation and business practice 20 1 3 3 4 0 1 1 0 2 5 Public health Years since completed dietetics training (n¼208) 0-10 110 10-20 43 >20 55 (n¼23) (n¼22) (n¼18) (n¼18) (n¼24) (n¼21) (n¼24) (n¼23) (n¼11) (n¼24) 9 15 10 11 13 11 17 17 5 2 8 2 1 6 5 5 6 4 1 5 6 5 7 1 6 5 1 2 5 17 RESEARCH 14 Table 4. Demographic characteristic details of study participants in pilot testing of the International Nutrition Care Process and Terminology Implementation Survey tool -- 2018 Volume - Number - RESEARCH differences in education systems and dietetics-related legislation (eg, registration) was required. Earlier research suggests that a certain degree of cultural adaption in survey development is needed to achieve high validity for the country specific context.42 The modular concept also appeared to be an effective way to accommodate cultural differences because it allowed each country to use the parts of the survey that appealed to its specific context and needs. For example, in Denmark and Sweden, Module 4 (NCP knowledge) was not included in this study because this module was considered not to appeal to their needs at the time of the survey. This is also a good illustration of the cultural dimensions within countries that need to be considered in a multinational research project.43 Although cultural differences exist, the final version of the INIS tool showed high content validity and testeretest reliability in most included countries. In Greece, testeretest reliability was slightly lower than in the other participating countries, which might be explained by the fact that the NCP/ NCPT still is very new among Greek dietetics practitioners. Thus, the lower reliability on especially the knowledge questions in Module 4 might just show that NCP/NCPT knowledge is lower among Greek dietetics practitioners. We suggest that a future survey study that includes more Greek participants will show whether this conclusion is correct or that there might be other explanations for the Greek results. As a part of the multinational collaboration, the translation process provided several insights, which will be valuable in future international dietetics research projects. Continuous evaluation and revision of translations during survey development is a time-consuming endeavor. However, this stepwise translation and continuous testing was performed because it is recommended to ensure equivalence between the original survey and the translated versions.36,44,45 Back translation is often recommended during translation evaluation processes. This entails translation to the target language, then translation back to the original language by another translator, with comparisons then made between the original and translated versions.46 However, because several limitations have been identified with back-translation, (eg, literal translation and missing information)42,47 we opted to conduct a continuous evaluation followed by a final expert quality check. This has also been the authors’ experience in earlier translation work, such as with the Swedish NCPT translations.45 The recommended number of experts in a quantitative content validity test is between three and 10.35 In this study, we included three experts from each country, which could be viewed as a small sample size, increasing the risk of overestimating the content validity using the S-CVI-Universal Agreement but underestimating validity using the S-CVIAverage. On the other hand, the overall international sample of experts was 45, which in turn can be viewed as a too large sample size, increasing the risk of underestimating the validity using the S-CVI-Universal Agreement but overestimating validity using the S-CVI-Average. Therefore, both these measurements were presented, indicating an acceptable level of content validity. Using the criteria from Polit and Beck,37 the INIS tool already in the first step showed excellent content validity, with a S-CVI-Average of 0.98 and with a SCVI-Universal Agreement exceeding 0.8, despite the large sample of experts. Also, for each separate country and -- 2018 Volume - Number - language, the survey tool had excellent content validity. The comprehensive development procedure and the earlier experience of the dietetics practitioners and researchers who participated in the first draft of the survey may contribute to this high content validity. The INIS tool was constructed based on the experiences of earlier national NCP/NCPT implementation surveys, and several of the researchers participating in drafting the first version of the survey had prior experiences with NCP/NCPT surveys. Still, in the cognitive interviews, additional ambiguities and unclear response options were discovered that needed revision. Several researchers have pointed out that a traditional survey pretest does not capture all ambiguities in a survey tool,29,38,48,49 which is why a multiapproach evaluation, including cognitive interviews, is needed. Following this advice, certain parts of the survey tool were further clarified and country specific adaptions of questions and response options were used to increase validity in the country-specific contexts. The sample sizes in this study could be considered rather low per country; however, this needs to be considered in relation to the size of the dietetic profession in each country. For example, in Norway, in total 29 dietitians participated in the study, constituting almost 6% of the total Norwegian population of dietitians. The French version of the survey was tested both in Canada and Switzerland, including only 13 participants in total. The reason for this is due to the smaller number of French-speaking dietitians in these countries. A suggestion for future development and validation of the INIS tool is to further test validity and reliability of the French version in a country with a larger population of Frenchspeaking dietitians. Similar further testing should also be performed for the German version, which was only tested in Switzerland, including in total 11 participants. The selection of experts and pilot study participants plays an important role in the testing of a survey.50 It is important to include the views of both expert users and nonexperts when testing an instrument. In the first two testing steps, an inclusion criterion was familiarity with the NCP/NCPT. In the final step, both NCP/NCPT users and nonusers were invited, but it is likely that nutrition and dietetics practitioners volunteering for this study had more knowledge and interest regarding the NCP/NCPT compared with typical nutrition and dietetics practitioners in the included countries. The results from the pilot study indeed do suggest this, because overall the responses were positive regarding NCP/NCPT attitudes and many respondents also indicated using the NCP/NCPT in their practice. Having nutrition and dietetics practitioners who had more experience with the NCP/NCPT could be considered a limitation of this study. In the case that more nonusers had participated in the pilot study, more alternative interpretations of questions, or difficult-to-understand questions could have been discovered. The recruitment of participants did aim to include as broad a range of background and experiences as possible. The most-described approach for survey development is starting from scratch, which involves identifying a number of main constructs upon which the survey questions are developed.30 The approach used in this study was a different process that involved modifying and combining different question sets used in earlier US, Canadian, and Australian surveys.51 This approach was taken because many of the included questions have already been tested in different JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 15 RESEARCH 16 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS Table 5. Country-specific testeretest reliability of the International Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Terminology (NCPT) Implementation Survey Australia (n[5) Canada (n[5) Denmark (n[4) Greece (n[4) Ireland (n[4) New Zealand (n[4) Norway (n[3) Sweden (n[5) United Switzerland States (n[3) (n[3) Testeretest Krippendorff’s a (95% CI)! 0.82 (0.70-0.92) 0.90 0.89 0.86 (0.75-0.96) (0.81-0.97) (0.80-0.98) 0.91 (0.83-0.98) 1.00 (0.99-1.00) 0.93 (0.83-1.00) 0.98 0.87 (0.93-1.00) (0.75-0.97) 0.87 (0.69-1.00) Module 2: NCP/ 0.90 (0.86-0.94) 0.90 0.91 0.62 (0.54-0.70) NCPT (0.86-0.93) (0.84-0.95) implementationa 0.94 (0.90-0.96) 0.92 (0.89-0.94) 0.86 (0.80-0.91) 0.87 0.96 (0.84-0.90) (0.95-0.97) 0.92 (0.86-0.96) Module 3: NCP/ NCPT attitudesb 0.52 (0.38-0.65) 0.83 0.48 0.64 (0.45-0.80) (0.69-0.92) (0.25-0.69) 0.74 (0.58-0.88) 0.66 (0.50-0.80) 0.70 (0.51-0.87) 0.75 0.58 (0.63-0.85) (0.38-0.75) 0.50 (0.22-0.77) Module 4: NCP/ NCPT knowledge 0.94 (0.83-1.00) 0.82 N/Ac (0.57-1.00) All modules together 0.93 (0.91-0.95) 0.92 0.91 0.88 (0.84-0.92) (0.88-0.94) (0.87-0.94) Module 1: Demographic information 0.33 (-0.17-0.76) 1.00 (1.00-1.00) 0.98 (0.95-1.00) 0.99 (0.97-1.00) N/A 1.00 (1.00-1.00) 0.90 (0.71-1.00) 0.96 (0.95-0.97) 0.95 (0.93-0.96) 0.92 (0.89-0.94) 0.91 0.96 (0.89-0.93) (0.95-0.97) 0.94 (0.91-0.96) Some questions in Module 2 were modified after this test to increase applicability for participants, adding comment fields “not applicable” and “I don’t know” response options. All questions in Module 3 were modified after this test to increase applicability for participants, adding comment fields and “not applicable” response options. c N/A¼not applicable. a b -- 2018 Volume - Number - RESEARCH contexts and languages, and shown good validity and reliability. It also means that comparisons can be made between the survey results using the INIS tool and earlier surveys. This approach though brings with it some limitations, such as difficulties establishing the underlying constructs in the confirmatory factor analysis for Module 3 (NCP/NCPT attitudes). The skewed distribution of responses might also have contributed to these difficulties because a majority of the respondents were very familiar with NCP/NCPT. Parts of the INIS tool is a further development of two earlier survey tools: the Canadian Alberta Health Services Survey and the Australian ASK-NCP survey, which in turn are based on earlier US surveys.22,31-33 The ASK-NCP survey is the only previously tested and published NCP/NCPT implementation survey, and parts of the ASK-NCP and INIS survey tools, mainly Module 4 (NCP/NCPT knowledge), are the same. However, whereas the ASK-NCP survey focused on an earlier stage of NCP/NCPT implementation, the INIS tool was developed to further assess implementation in countries where implementation has been ongoing. Although the ASK-NCP survey targets attitudes and prerequisites before, and at an early stage of implementation, the INIS tool is more focused on the degree of NCP/NCPT use and the experiences of this usage. In this way, the ASK-NCP and INIS survey tools complement each other, and we suggest that translation and testing of the ASK-NCP survey in a similar multinational context would be very valuable. The modular concept used in the INIS tool makes it possible for researchers and evaluators to use only the parts of the survey that are considered most valuable in their specific context. Also, it is possible to combine certain of the four INIS modules with other survey tools, for example the ASK-NCP survey, and adjust accordingly to the stage of NCP/NCPT implementation in a certain country. However, these possible modifications of the tool will of course require further validation studies to ensure acceptable validity and reliability. Considering that the INIS tool is intended to allow for comparisons over time and across contexts, there is some need for further testing. We welcome future research to assess further aspects of the INIS tool, such as its sensitivity for capturing changes in implementation over time. References 1. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition terminology reference manual (eNCPT): Dietetics language for nutrition care. http://ncpt. webauthor.com. Accessed August 7, 2018. 2. Lacey K, Pritchett E. Nutrition Care Process and Model: ADA adopts road map to quality care and outcomes management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(8):1061-1072. 3. Swan WI, Vivanti A, Hakel-Smith NA, et al. Nutrition Care Process and Model update: Toward realizing people-centered care and outcomes management. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(12):2003-2014. 4. Bueche J, Charney P, Pavlinac J, Skipper A, Thompson E, Myers E. Nutrition Care Process and Model part I: The 2008 update. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(7):1113-1117. 5. Stein K. Propelling the profession with outcomes and evidence: Building a robust research agenda at the Academy. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(10 suppl):S62-S78. 6. Thompson KL, Davidson P, Swan WI, et al. Nutrition Care Process chains: The “missing link” between research and evidence-based practice. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(9):1491-1498. 7. Bueche J, Charney P, Pavlinac J, Skipper A, Thompson E, Myers E. Nutrition Care Process part II: Using the International Dietetics and Nutrition Terminology to document the Nutrition Care Process. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(8):1287-1293. 8. Swedish Association of Clinical Dietitians. Position statement NCP and NCPT (updated version). http://www.drf.nu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/02/1602015.updatedeng.DRFstatementNCP. pdf. Accessed August 7, 2018. 9. European Federation of the Associations of Dietitians Professional Practice Committee. Vision paper: The implementation of a Nutrition Care Process (NCP) and Standardized Language (SL) among dietitians in Europe Vision 2020. http://www.drf.nu/wp-content/uploads/2 014/08/EFAD-Prof-Practice-Committee-2014.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2018. 10. International Confederation of Dietetic Associations. From the Chair of the Board. In: Dietetics Around the World: The Newsletter for the ICDA. http://www.internationaldietetics.org/Newsletter/Vol18Issue2/ Fall-2011-newsletter.aspx. Accessed August 7, 2018. 11. Atkins M, Basualdo-Hammond C, Hotson B. Canadian perspectives on the Nutrition Care Process and international dietetics and nutrition terminology. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2010;71(2):106. 12. Vivanti A, Ferguson M, Porter J, O’Sullivan T, Hulcombe J. Increased familiarity, knowledge and confidence with Nutrition Care Process Terminology following implementation across a statewide healthcare system. Nutr Diet. 2015;72(3):222-231. 13. Lövestam E, Orrevall Y, Koochek A, Andersson A. The struggle to balance system and lifeworld: Swedish dietitians’ experiences of a standardised nutrition care process and terminology. Health Sociol Rev. 2016;25(3):240-255. 14. Corado L, Pascual R. Successes in implementing the Nutrition Care Process and standardized language in clinical practice. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(9):A42. 15. Lövestam E, Boström A-M, Orrevall Y. Nutrition Care Process implementation: Experiences in various Swedish dietetic environments. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(11):1738-1748. 16. Hakel-Smith N, Lewis NM, Eskridge KM. Orientation to Nutrition Care Process standards improves nutrition care documentation by nutrition practitioners. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(10):1582-1589. 17. Lövestam E, Orrevall Y, Koochek A, Karlström B, Andersson A. Evaluation of a Nutrition Care Process-based audit instrument, the DietNCP-Audit, for documentation of dietetic care in medical records. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28(2):390-397. 18. Swedish Association of Clinical Dietitians. Sammanställning av DRFs NCP-enkät [Summary of DRF’s NCP survey]. http://www.drf.nu/wpcontent/uploads/2014/08/NCPbearbetadYO.2013.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2018. 19. Papoutsakis C, Orrevall Y; EFAD Professional Practice Committee. The use of standardized language among dietitians in Europe. Dietistaktuellt. 2012;21(1):32-33. 20. Report on Knowledge and Use of a Nutrition Care Process & Standardised Language by Dietitians in Europe. The Netherlands: European Federation of the Associations of Dietitians; 2012. 21. Eriksson V. Utvärdering av NCP/IDNT-implementering [evaluation of NCP/IDNT implementation]. Dietistaktuellt. 2011;20(5):30-31. CONCLUSIONS New opportunities to compare NCP/NCPT implementation are now possible over time and between countries due to the creation of a standardized survey instrument tested across several countries. We expect this tool will be valuable in future research to assess different implementation interventions and strategies. This study has also provided valuable insights about collaboration and survey development across cultures and countries, which will contribute to future international NCP/NCPT development work. The collaborative development of this survey is an important step in the development and advancement of the dietetics profession. We also anticipate that the INIS tool will prove to be valuable, both for international and national research, evaluation, and development projects in dietetics to optimize patient safety and the quality of nutrition care. -- 2018 Volume - Number - JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 17 RESEARCH 22. Porter J, Devine A, Vivanti A, Ferguson M, O’Sullivan TA. Development of a Nutrition Care Process implementation package for hospital dietetic departments. Nutr Diet. 2015;72(3):205-212. 37. Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489-497. 23. Porter J, Devine A, O’Sullivan T. Evaluation of a Nutrition Care Process implementation package in hospital dietetic departments. Nutr Diet. 2015;72(3):213-221. 38. Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. 39. 24. Vivanti A, O’Sullivan TA, Porter J, Hogg M. Successful long-term maintenance following Nutrition Care Process Terminology implementation across a statewide healthcare system. Nutr Diet. 2017;74(4):372-380. Grube JW, Morgan M, Kearney KA. Using self-generated identification codes to match questionnaires in panel studies of adolescent substance use. Addict Behav. 1989;14(2):159-171. 40. Vivanti A, Lewis J, O’Sullivan TA. The Nutrition Care Process Terminology: Changes in perceptions, attitudes, knowledge and implementation amongst Australian dietitians after three years. Nutr Diet. 2017;75(1):87-97. Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods. 1999;4(3):272. 41. Hayes AF, Krippendorff K. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun Methods Meas. 2007;1(1): 77-89. 26. Radhakrishna RB. Tips for developing and testing questionnaires/ instruments. J Ext. 2007;45(1):1-4. 42. McGorry SY. Measurement in a cross-cultural environment: Survey translation issues. Qual Market Res Int J. 2000;3(2):74-81. 27. Rattray J, Jones MC. Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(2):234-243. 43. Chevrier S. Cross-cultural management in multinational project groups. J World Bus. 2003;38(2):141-149. 28. Peterson RA. Constructing Effective Questionnaires. Vol 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. 44. 29. Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(3):229-238. Acquadro C, Conway K, Hareendran A, Aaronson N, Issues ER. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value Health. 2008;11(3):509-521. 30. Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to their Development and Use. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2014. 45. McGreevy J, Orrevall Y. Translating terminology for the Nutrition Care Process: The Swedish experience (2010-2016). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(3):469-476. 31. Gourley JL. Assessing Perceptions Toward Implementation of the Nutrition Care Process among Registered Dietitians in Northeast Tennessee. Johnson City, TN: Faculty of the Department of Family and Consumer Studies, East Tennessee State University; 2007. 46. Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1(3):185-216. 47. McGreevy J, Orrevall Y, Belqaid K, Bernhardson BM. Reflections on the process of translation and cultural adaptation of an instrument to investigate taste and smell changes in adults with cancer. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28(1):204-211. 48. Presser S, Couper MP, Lessler JT, et al. Methods for testing and evaluating survey questions. Public Opin Q. 2004;68(1):109130. 49. Desimone LM, Le Floch KC. Are we asking the right questions? Using cognitive interviews to improve surveys in education research. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2004;26(1):1-22. Grant JS, Davis LL. Selection and use of content experts for instrument development. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(3):269-274. 25. 32. Gardner-Cardani J, Yonkoski D, Kerestes J. Nutrition Care Process implementation: A change management perspective. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(8):1429-1433. 33. Mathieu J, Foust M, Ouellette P. Implementing Nutrition Diagnosis, step two in the Nutrition Care Process and Model: Challenges and lessons learned in two health care facilities. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(10):1636-1640. 34. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. NCP orientation tutorial quiz. https://ncpt.webauthor.com/encpt-tutorials. Accessed August 7, 2018. 50. 35. Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35(6):382-385. 51. 36. Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK. Instrument translation process: A methods review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(2):175-186. 18 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS Kitchenham BA, Pfleeger SL. Principles of survey research: Part 3: Constructing a survey instrument. ACM SIGSOFT. 2002;27(2): 20-24. -- 2018 Volume - Number - RESEARCH AUTHOR INFORMATION E. Lövestam is an assistant lecturer, Department of Studies, Nutrition and Dietetics, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. A. Vivanti is a research and development dietitian, Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, and senior lecturer, School of Human Movement and Nutrition Studies, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. A. Steiber is chief science officer, and C. Papoutsakis is a senior director, Nutrition and Dietetics Data Science Center, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Chicago, IL. A.-M. Boström is a registered nurse, an associate professor, and a senior lecturer, Department of Neurobiology, Care Science and Society, Division of Nursing, Karolinska Institute, Huddinge, Sweden; a university nurse, Theme Aging, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden; and a professor II, Department of Nursing, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Haugesund, Norway. A. Devine is a registered public health nutritionist and a professor of public health and nutrition, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Western Australia, Australia. O. Haughey is a senior dietitian and project manager, Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute, Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. C. M. Kiss is a team leader, Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland. N. R. Lang is a senior lecturer, Department of Nutrition and Health, VIA University College, Aarhus, Denmark. J. Lieffers is an assistant professor, College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. L. Lloyd is a senior renal dietitian, Nutrition and Dietetics, Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand. T. A. O’Sullivan is a senior lecturer, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Western Australia, Australia. L. Thoresen is a clinical dietitian, Cancer Clinic, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, and a clinical dietitian, National Advisory Unit on Disease-Related Malnutrition, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway. Y. Orrevall is head of research and development, Education and Innovation, Function Area Clinical Nutrition, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, and an associated researcher, Department of Learning, Informatics, Management, and Ethics, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. Address correspondence to: Elin Lövestam, PhD, RD, Department of Food, Nutrition, and Dietetics, Uppsala University, PO Box 560, SE-751 22 Uppsala, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected] STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. FUNDING/SUPPORT The foundation Kronprinsessan Margaretas Minnesfond funded the position of the study coordinator, Elin Lövestam. The Canadian component of this study was funded by the Canadian Foundation for Dietetic Research as a special projects grant from Dietitians of Canada. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank all those who participated in this validation study as experts, interviewees, or pilot study participants. The authors also thank Carlota Basualdo-Hammond, MSc, MPH, RD, and Marlis Atkins, RD, for developing the Alberta Health Services Survey as well as the national dietetic associations in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States for their support during this study. In addition, the authors thank the members of the Dietitians of Canada NCP Leadership Committee (Marlis Atkins, RD; Isabelle Galibois, PhD, RD; Leslie Harden, MHS, RD; Brenda Hotson, RD, MSc; Janie Levesque, MSc RD; Jane Paterson, MSc, RD; and Linda Sunderland, RD) for providing guidance with the Canadian component of the study, and Kate Comeau, MSc, RD, for her assistance with participant recruitment in Canada. International Nutrition Care Process/Nutrition Care Process Terminology Implementation Survey Consortium members (collaborators) include Clare Corish, PhD, RD (School of Public Health, Physiotherapy and Sports Science, University College, Dublin, Ireland); Corinne Eisenbraun, MA, RD (Dietitians of Canada, Toronto, Ontario, Canada); Rhona Hanning, PhD, RD (School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada; Ida Kristiansen, MSc, RD (Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway); Sissi Stove Lorentzen, MS, RD (Norwegian Association of Dietitians Affiliated with the Norwegian Association of Researchers, Oslo, Norway); Arwen K. MacLean, MSc, RD (Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland); and Charlotte Peerson, MSc, RD (VIA University College, Aarhus, Denmark). AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS Y. Orrevall, E. Lövestam, A. Steiber, and A. Vivanti participated in initial discussions and planning of the study; all other authors participated in the design of the project by critical revisions of the initial plans. E. Lövestam coordinated the international data collection in collaboration with Y. Orrevall; all other authors were involved in local data collection. E. Lövestam was responsible for data analysis and interpretation and drafted the manuscript; Y. Orrevall participated in data interpretation and provided critical revision of the manuscript; and all other authors provided critical revision on data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript development. All consortium members assisted in research planning or data collection. All authors and consortium members read and approved the final version of the manuscript. -- 2018 Volume - Number - JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF NUTRITION AND DIETETICS 19