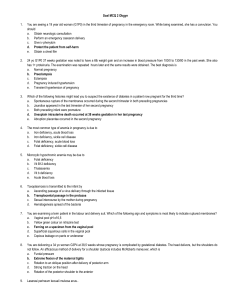

100 100 Trichomoniasis Michael F. Rein KEY FEATURES • Trichomoniasis is a common, sexually transmitted disease caused by a protozoan parasite that infects the urogenital tract of men and women. • The vagina is the most common site of infection in women. • Many infected women are asymptomatic, but clinical features include vaginal discharge, often yellow or green, often frothy; vulvovaginal irritation; and dysuria. • The urethra is the most common site of infection in men. • Most men with trichomoniasis do not have signs or symptoms; however, some men may exhibit urethral irritation and discharge or mild burning after urination or ejaculation. • Traditionally, diagnosis and differential diagnosis may be made by wet mount of vaginal material; nucleic acid amplification techniques are available. • Trichomoniasis is treated with oral 5′-nitroimidazoles, although resistance is developing. INTRODUCTION Trichomoniasis is a common, worldwide, urogenital infection with Trichomonas vaginalis.1,2 It is a frequent cause of sympt­ omatic vaginitis and a less common cause of nongonococcal urethritis (NGU). EPIDEMIOLOGY Trichomoniasis is transmitted primarily by penile–vaginal and possibly by penile–anal coitus.3 Because it is sexually transmitted, it is strikingly associated with higher risk for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and coincident STIs should be sought. Trichomoniasis has a relatively increased prevalence among women aged 40 to 49 years.4,5 Sexual partners, even if asymptomatic, should be treated simultaneously, which demonstrably increases cure rates. Trichomoniasis increases the risk of acquisition of HIV infection,2,6 and co-infection increases viral shedding.2,6,7 Women who deliver while infected rarely transmit the infection to the neonate, in whom it may present vaginally or, rarely, in the respiratory tract.8,9 An estimated 3 to 5 million new cases occur annually in the United States, with an overall prevalence among women of about 3%. Its incidence in the United States may have gradually decreased over the last 40 years, perhaps due to the imidazoles extensively administered to the same population for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis.10,11 Infection is detected in about three-quarters of the male sexual partners of infected women,12 and reinfection is common. Although usually carried asymptomatically by men, T. vaginalis may cause NGU.13 Some studies suggest that male circumcision may reduce the likelihood of transmission. Natural History, Pathogenesis, and Pathology T. vaginalis damages squamous epithelial cells through direct contact,2 which causes microulcerations and microscopic hemorrhages of the vaginal walls and exocervix. Columnar epithelium is not affected, and thus trichomoniasis presents with vaginitis but not with endocervicitis. The simultaneous presence of an endocervical discharge should alert the clinician to the possibility of co-incident infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, or Mycoplasma genitalium. Invasion of tissue does not occur. T. vaginalis is also isolated from the urethra in most infected women. Organisms can cause ulcerations beneath the prepuce. The immune response to trichomonal infection remains incompletely defined. Infection elicits an outpouring of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), which are easily visualized on wet mount and serve as an aid in differential diagnosis. A low-grade humoral response is detected in serum and vaginal secretion, but immunity to re-infection is not produced.2 CLINICAL FEATURES History In various series, 50% to 90% of women with trichomoniasis have symptoms. Individual symptoms are relatively non-specific. Many women with trichomoniasis have other STIs, and it is sometimes difficult to attribute specific clinical features to trichomoniasis alone. Vaginal discharge is recognized by 50% to 75% of infected women, but the discharge is considered malodorous by only 10%. One-quarter to one-half of infected women suffer vulvar irritation or pruritus, and up to 50% report dyspareunia. Dysuria may be internal or external. Lower abdominal discomfort is described by only 10% of women, and its presence, particularly if accompanied by an adnexal tenderness on bimanual examination, should suggest the possibility of coincident salpingitis from other pathogens, which may be more common in the presence of HIV.6 Some women report that symptoms began or were exacerbated immediately after the menstrual period. In experimentally induced infection, incubation periods ranged from 3 to 28 days. Most infected men come to treatment as sexual contacts of infected women. T. vaginalis causes a minority of cases of NGU, presenting as some combination of dysuria and urethral discharge, and resembling NGU of more common etiologies. Trichomonal urethritis is often considered when the condition fails to respond to standard antibacterial therapies.13,14 Rarely, epididy­ mitis is encountered, and the organism has been identified in the prostate.14 Physical Examination The vulva is erythematous in less than one-third of patients. On speculum examination, excessive discharge is noted in 50% to 75% of infected women. A yellow vaginal discharge suggests trichomoniasis, but the classically yellow or green, frothy discharge is seen in only a minority of patients. Indeed, bubbles are present in only 8% to 50% of infected women in various series, and because bubbles are also observed in bacterial vaginosis, their presence is non-specific. 731 732 PART 5 Protozoal Infections TABLE 100.1 Typical Features of Trichomoniasis and Differentials Trichomoniasis Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Bacterial Vaginosis SYMPTOMS Vulvar irritation Dysuria Odor 4+ 20% 0–2+ 4+ External 0 0–1+ 0 1+–4+ SIGNS Labial erythema Satellite lesions 1+–4+ 0 1+–4+ Frequent 0 0 DISCHARGE Consistency Color Adherence to vaginal walls Whiff test Alkalinity Frothy (25%) Yellow-green (25%) 0 60%–90% ≥4.7 (70%–90%) Minimal to curdy White Often 0 ≤4.5 Homogeneous, often frothy Gray, white Usually 70%–90% ≥4.7 (90%) BIMANUAL EXAMINATION Adnexal tenderness Vaginal wall tenderness Occasional 0–2+ 0 0–2+ 0 0 WET MOUNT Epithelial cells PMN/epithelial cell Bacteria Pathogens Normal ≥1 Rods or coccobacilli Trichomonads (60%) Normal Variable Rods Yeasts and pseudo-hyphae (50%) Clue cells (90%) ≤1 Coccobacilli and motile rods Non-specific PMN, Polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Vaginal wall erythema, occasionally with edema, is observed in 20% to 75% of cases. Punctate hemorrhages are detected on the vaginal walls or the exocervix (strawberry cervix) in about 2% of women during routine physical examination, but the characteristic hemorrhages are visualized in 45% by colposcopy. Mild adnexal tenderness is occasionally elicited on bimanual examination. This may be due to pelvic adenitis induced by the infection, but its presence should raise concern for coincident salpingitis. Complications Trichomoniasis is generally a benign disease. Gestational trichomoniasis has been associated with premature rupture of the fetal membranes and pre-term delivery.8,9 Trichomoniasis, with its brisk inflammatory response and microulcerations of the genital epithelium, may increase the risk of acquiring HIV.6,7 In addition, treatment of trichomoniasis reduces the concentration of HIV in vaginal secretions about fourfold, theoretically reducing the risk of transmitting the HIV.7 PATIENT EVALUATION, DIAGNOSIS, AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Clinicians often manage symptomatic women who present with some combination of vaginal discharge, vulvar irritation, and odor (Table 100.1). A history of contact with a new partner supports the diagnosis of sexually transmitted vaginitis. Odor without much irritation is more consistent with bacterial vaginosis than with trichomoniasis, in which irritation is relatively more prominent. After completing the physical examination, it is useful to determine the pH of vaginal secretions. This is conveniently accomplished by inserting a strip of indicator paper into the vaginal discharge pooled in the lower lip of the speculum. Normal vaginal pH of 4.7 or less is maintained in most patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Vaginal pH is elevated above 4.7 in most women with trichomoniasis, but an elevated pH is also found in most women with bacterial vaginosis and is not specific. The pH of vaginal material may be artifactually elevated if contaminated with cervical discharge or semen. After the pH has been determined, several drops of 10% to 20% potassium hydroxide should be added to the discharge in the speculum. The clinician then seeks the elaboration of a pungent, fishy, aminelike odor. This positive result of the whiff test is manifested by 75% of women with trichomoniasis, but also by most women with bacterial vaginosis. The whiff test is not positive in vulvovaginal candidiasis. Definitive diagnosis requires demonstration of the organism. Nucleic acid amplification techniques, when available, are the preferred method.2–4,12,14,15 T. vaginalis culture and antigen detection systems, which are less sensitive, are commercially available and may be used at point of care.16 Diagnosis in men is difficult and depends on molecular techniques.2,3,12,13 The Pap smear can detect trichomonal infection, but the Gram stain is useless. Traditionally, definitive diagnosis is made by wet mount. A swab of vaginal material can be agitated in about 1 mL of saline, and a drop is transferred to a microscope slide to which a coverslip is then applied. This wet mount is observed at 400× (Fig. 100.1) with the sub-stage condenser racked down and the sub-stage diaphragm closed. Its sensitivity for trichomoniasis is only about 60%, but the technique is also useful in differential diagnosis (Table 100.1). TREATMENT Decades of experience and old studies confirm the value of oral 5′-nitroimidazoles for treating men and women. Metronidazole or tinidazole are preferred in the United States, but in other parts of the world, ornidazole and nimorazole are used as well. High-dose vaginal suppositories are available in some areas, but low-dose metronidazole vaginal preparations, designed for bacterial vaginosis, are inadequate for trichomoniasis. Male partners should be treated simultaneously even if asymptomatic. Treatment of trichomoniasis can be effectively accomplished with metronidazole 2 g orally in a single dose, tinidazole 2 g orally in a single dose, or metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days.14 In HIV-infected patients, one should use the higher-dose regimen.17 Single-dose metronidazole (Category B) appears safe in pregnancy, but tinidazole (Category C) should not be used.18,19 In a multi-center, open-label, CHAPTER 100 Trichomoniasis Fig. 100.1 Trichomoniasis. Wet mount of vaginal discharge showing several round polymorphonuclear neutrophils and two ovoid trichomonads. Anterior flagella are visible. (Phase contrast, ×1000.) randomized controlled trial comparing single dose metronidazole (2 gm) versus 500 mg of metronidazole twice daily for 7 days, recipients of the 7 day course werte less likely to be T. vaginalis positive at test of cure 4 weeks after treatment than in the singledose group (11% versus 19%).20 Recurrent trichomoniasis in the absence of re-infection may result from resistance to nitroimidazoles,21 and one might first attempt re-treatment with the 7-day regimen, moving to 2 g/day orally for 7 days for further failure.14 Limited data support the use of tinidazole in this setting.1,14 The optimal management of patients unable to use nitroimidazoles due to severe allergy or other reason is poorly defined.1,14 REFERENCES 1. Meites E, Gaydos CA, Hobbs MM, et al. A review of evidence-based care of symptomatic trichomoniasis and asymptomatic Trichomonas vaginalis infections. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(S8):S839–48. 2. Oliveira AS, Ferrão AR, Pereira FM, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis: an updated overview towards diagnostic improvement. Acta Parasitol 2016;61:10–21. 3. Consentino LA, Campbell T, Jett A, et al. Use of nucleic acid amplification testing for the diagnosis of anorectal sexually transmitted infections. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:2005–8. 733 4. Ginocchio CC, Chapin K, Smith JS, et al. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis and coinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States as determined by the Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis nucleic acid amplification assay. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:2601–8. 5. Allsworth JE, Ratner JA, Peipert JF. Trichomoniasis and other sexually transmitted infections: results from the 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Sex Transm Dis 2009;26:728–44. 6. Kissinger P, Adamski A. Trichomoniasis and HIV interactions: a review. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89:426–33. 7. Anderson BL, Firnhaber C, Liu T, et al. Effect of trichomoniasis therapy on genital HIV viral burden among African women. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:638–42. 8. Silver BJ, Guy RJ, Kaldon JM, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis as a cause of perinatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2014;41:369–76. 9. Cotch MF, Pastorek JG 2nd, Nugent RP, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Sex Transm Dis 1997;24:353–60. 10. Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men; prevalence and incidence estimates. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:187–93. 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2016. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. 12. Hobbs MM, Lapple DM, Lawing LF, et al. Methods for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in the male partners of infected women: implications for control of trichomoniasis. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:3994–9. 13. Seña AC, Lensing S, Rompalo A, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Trichomonas vaginalis in men with nongonococcal urethritis: predictors and persistence after therapy. J Infect Dis 2012;206:357–65. 14. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015;64:72–5. 15. Van Der Pol B. Clinical and laboratory testing for Trichomonas vaginalis infection. J Clin Microbiol 2016;54:7–12. 16. Castillo AD, Bristow CC, Peeling R, et al. Point-of-care sexually transmitted infection diagnostics: proceedings of the STAR Sexually Transmitted Infection-Clinical Trial Group programmatic meeting. Sex Transm Dis 2017;44:211–18. 17. Kissinger P, Mena L, Levison J, et al. A randomized treatment trial: single versus 7-day dose of metronidazole for the treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:565–71. 18. Gulmezoglu AM, Azhar M. Interventions for trichomoniasis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(5):CD000220. 19. Koss CA, Baras DC, Lane SD, et al. Investigation of metronidazole use during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:4800–5. 20. Kissinger P, Muzny CA, Mena LA, et al. Single-dose versus 7-day-dose metronidazole for the treatment of trichomoniasis in women: an openlabel, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18(11):1251–9. 21. Kirkcaldy RD, Augostini P, Asbel LE, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis antimicrobial drug resistance in 6 US cities, STD Surveillance Network, 2009-2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:939–43. 100