Uploaded by

common.user36582

Transfer Function (2): Rotational, Gears, Electromechanical Systems

advertisement

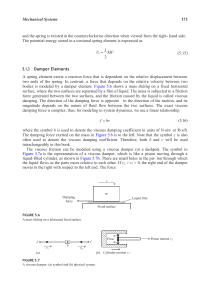

Transfer Function (2) - Rotational Mechanical System TF √ - TF for Systems with Gears √ - Electromechanical System TF √ 1 Rotational Mechanical System TF Units: T(t): N-m (newton-meters); 𝜃 𝑡 : rad (radians); 𝜔 𝑡 : rad/s (radians/second); K: N-m/rad (newton-meters/radian), J: kg-𝑚2 (kilograms-meter𝑠 2 - newton-meters-second𝑠 2 /radian). 2 3 Ex.: Find the transfer function 𝜃2 𝑠 𝑇 𝑠 . The rod is undergoing torsion. A torque is applied at the left, and the displacement is measured at the right. Physical system. Schematic diagram The system is considered as a lumped parameter system. So that the torsion acts like a spring concentrated at one particular point in the rod, with an inertia 𝐽1 to the left and an inertia 𝐽2 to the right . The damping inside the flexible shaft is negligible. There are two degrees of freedom, since each inertia can be rotated while the other is held still. Hence it will take two simultaneous equations to solve the system. 4 Free-body diagram of 𝐽1 : Torques on 𝐽1 due only to motion of 𝐽1 . 𝐽2 is held still. Torques on 𝐽1 due only to motion of 𝐽2 . 𝐽1 is held still. Final free-body diagram for 𝐽1 . The same process is repeated for 𝐽2 : 5 Free-body diagram of 𝐽2 : Torques on 𝐽2 due only to motion of 𝐽2 . 𝐽1 is held still. Torques on 𝐽2 due only to motion of 𝐽1 . 𝐽2 is held still. Final free-body diagram for 𝐽2 . 6 Summing torques: 𝐽1 𝑠 2 + 𝐷1 𝑠 + 𝐾 𝜃1 𝑠 − 𝐾𝜃2 𝑠 = 𝑇(𝑠) −𝐾𝜃1 𝑠 + 𝐽2 𝑠 2 + 𝐷2 𝑠 + 𝐾 𝜃2 𝑠 = 0 TF: 𝜃2 (𝑠) 𝐾 = 𝑇(𝑠) ∆ 𝐽1 𝑠 2 + 𝐷1 𝑠 + 𝐾 ∆= −𝐾 −𝐾 𝐽2 𝑠 2 + 𝐷2 𝑠 + 𝐾 7 TF for systems with gears Gear 1 (input gear), radius 𝑟1 , 𝑁1 teeth, is rotated through angle 𝜃1 𝑡 due to a torque 𝑇1 (𝑡). Gear 2 (output gear), radius 𝑟2 , 𝑁2 teeth, responds by rotating through angle 𝜃2 (𝑡) and delivering a torque, 𝜃2 𝑡 . Assuming that there is no backlash phenomena. As the gear turn, the distance traveled along each gear’s circumference is the same: 𝑟1 𝜃1 = 𝑟2 𝜃2 or 𝜃2 𝑟1 𝑁1 = = 𝜃1 𝑟2 𝑁2 Since the ratio of the number of teeth along the circumference is in the same proportion as the ratio of the radii. 8 If we assume that the gears are lossless, that is they do not absorb or store energy, the energy into Gear 1 equals the energy out of Gear 2 (namely inertia and damping are negligible). Relationship between the input torque and the delivered torque: 𝑇1 𝜃1 = 𝑇2 𝜃2 Then 𝑇2 𝜃1 𝑁2 = = 𝑇1 𝜃2 𝑁1 Thus the torques are directly proportional to the ratio of the number of teeth. TF for angular displacement in lossless gears. TF for torque in lossless gears. 9 Mechanical impedances driven by gears a. Rotational system driven by gears. Gears driving a rotational inertia, spring, and viscous damper. b. Equivalent system at the output after reflection of input torque. 𝑇1 can be reflected to the output by 𝑁 multiplying by 𝑁2 . The equation of motion: 1 𝑁2 2 𝐽𝑠 + 𝐷𝑠 + 𝐾 𝜃2 𝑠 = 𝑇1 (𝑠) 𝑁1 𝑁1 𝑁2 2 𝐽𝑠 + 𝐷𝑠 + 𝐾 𝜃 𝑠 = 𝑇1 (𝑠) 𝑁2 1 𝑁1 Then 2 2 2 𝑁1 𝑁 𝑁 𝑁1 1 1 𝐽 𝑠2 + 𝐷 𝑠+𝐾 𝜃 𝑠 = 𝑇1 (𝑠) 𝑁2 𝑁2 𝑁2 𝑁2 1 c. Equivalent system at the input after reflection of impedances without gears. Rotational mechanical impedances can be reflected through gear trains by multiplying the mechanical impedance by the ratio 𝑁𝑢𝑚𝑏𝑒𝑟 𝑜𝑓 𝑡𝑒𝑒𝑡ℎ 𝑜𝑓 𝑔𝑒𝑎𝑟 𝑜𝑛 𝑑𝑒𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑛𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑠ℎ𝑎𝑓𝑡 𝑁𝑢𝑚𝑏𝑒𝑟 𝑜𝑓𝑡𝑒𝑒𝑡ℎ 𝑜𝑓 𝑔𝑒𝑎𝑎𝑟 𝑜𝑛 𝑠𝑜𝑢𝑟𝑐𝑒 𝑠ℎ𝑎𝑓𝑡 Where the impedance to be reflected is attached to the source shaft and is being reflected to the destination shaft. System with lossless gears Ex.: Find the TF 𝜃2 𝑠 𝑇1 𝑠 of the rotational mechanical system with gears (a). First, reflect the impedance 𝐽1 and 𝐷1 and torque 𝑇1 on the input shaft to the output (b). Here the impedance are reflected by 𝑁2 /𝑁1 2 and the torque is reflected by 𝑁2 /𝑁1 . So the equation of motion 𝑁2 𝐽𝑒 𝑠 + 𝐷𝑒 𝑠 + 𝐾𝑒 𝜃2 𝑠 = 𝑇1 (𝑠) 𝑁1 2 𝐽𝑒 = 𝑁2 2 𝐽1 𝑁1 + 𝐽2 𝐷𝑒 = 𝑁2 2 𝐷1 𝑁1 + 𝐷2 TF: 𝜽𝟐 (𝒔) 𝑵𝟐 /𝑵𝟏 𝑮 𝒔 = = 𝑻𝟏 (𝒔) 𝑱𝒆 𝒔𝟐 + 𝑫𝒆 𝒔 + 𝑲𝒆 𝐾𝑒 = 𝐾2 In orderto eliminate gears with large radii, a gear train (see the figure) is used to implement large gear ratios by cascading smaller gear ratios. Next to each rotation, the angular displacement relative to 𝜃1 has been calculated. The equivqlent gear ratio is the product of the individual gear ratios. So: 𝑁1 𝑁3 𝑁5 𝜃4 = 𝜃 𝑁2 𝑁4 𝑁6 1 Gears with loss Ex.: Find the TF 𝜃1 (𝑠)/𝑇1 (𝑠). We reflect all the impedance to the input shaft, 𝜃1 . The equation of motion: 𝐽𝑒 𝑠 2 + 𝐷𝑒 𝑠 𝜃1 𝑠 = 𝑇1 (𝑠) 𝐽𝑒 = 𝐽1 + 𝐽2 + 𝐽3 TF: 𝑮 𝒔 = 𝜽𝟏 (𝒔) 𝑻𝟏 (𝒔) = 𝑁1 2 𝑁2 + 𝐽4 + 𝐽5 𝑁1 𝑁3 2 ; 𝑁2 𝑁4 𝐷𝑒 = 𝐷1 + 𝑁1 2 𝐷2 𝑁2 𝟏 𝑱𝒆 𝒔𝟐 +𝑫𝒆 𝒔 System using a gear train Equivalent system at the input Electromechanical System TF A motor is an electromechanical component that yields a displacement (mechanical) output for a voltage (electrical) input. Armature-controlled dc servomotor. A magnetic field is developed by stationnary permanent magnets called the fixed field. A rotating circuit called the armature through which current 𝑖𝑎 (𝑡) flows, passes through this magnetic field at right angles and feels a force, 𝐹 = 𝐵 𝑙 𝑖𝑎 (𝑡) B is the magnetic field strength; 𝑙 is the length of the conductor. The resulting torque turns the rotor, the rotating member of the motor. A conductor moving at right angles to a magnetic field generates a voltage at the terminals of the conductor equal to 𝑒=𝐵𝑙𝑣 e is the voltage; v is the velocity of the conductor normal to the magnetic field. 15 Since the current-carrying armature is rotating in a magnetic field, its voltage is proportional to speed: 𝑑𝜃𝑚 (𝑡) 𝑣𝑏 𝑡 = 𝐾𝑏 𝑑𝑡 𝑣𝑏 𝑡 : back electromotive force (back emf); 𝐾𝑏 : a constant of proportionality (the back emf constant); 𝑑𝜃𝑚 𝑡 𝑑𝑡 = 𝜔𝑚 (𝑡): angular velocity of the motor. Laplace transform: 𝑉𝑏 𝑠 = 𝐾𝑏 𝑠𝜃𝑚 (𝑠) (a) So the loop equation arround the armature circuit: 𝑅𝑎 𝐼𝑎 𝑠 + 𝐿𝑎 𝑠𝐼𝑎 𝑠 + 𝑉𝑏 𝑠 = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑠) (b) The torque developed by the motor is proportional to the armature current: 𝑇𝑚 𝑠 = 𝐾𝑡 𝐼𝑎 𝑠 → 𝐼𝑎 𝑠 = 1 𝑇 (𝑠) 𝐾𝑡 𝑚 (c) 𝑇𝑚 is the torque developed by the motor; 𝐾𝑡 is a constant of proportionality called the motor torque constant which depends on the motor and magnetic 16 field characteristics. The value of 𝐾𝑡 is equal to the value of 𝐾𝑏 . Substituting (a) and (c) into (b): 𝑅𝑎 +𝐿𝑎 𝑠 𝑇𝑚 (𝑠) + 𝐾𝑡 𝐾𝑏 𝑠𝜃𝑚 𝑠 = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑠) (d) We must now find 𝑇𝑚 𝑠 in term of 𝜃𝑚 (𝑠). The figure shows a typical equivalent mechanical loading on a motor. 𝐽𝑚 is the equivalent inertia at the armature and includes both the armature inertia and the load inertia reflected to the armature. 𝐷𝑚 is the equivalent viscous damping at the armature and includes both the armature viscous damping and the load viscous damping reflected to the armature. Then 𝑇𝑚 𝑠 = 𝐽𝑚 𝑠 2 + 𝐷𝑚 𝑠 𝜃𝑚 (𝑠) (e) (e) → (d): 𝑅𝑎 + 𝐿𝑎 𝑠 𝐽𝑚 𝑠 2 + 𝐷𝑚 𝑠 𝜃𝑚 (𝑠) + 𝐾𝑏 𝑠𝜃𝑚 𝑠 = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑠) 17 𝐾𝑡 𝐿𝑎 , the armature inductance, is assumed to be small compared to the armature resistance, 𝑅𝑎 , which is usual for a dc motor, so 𝑅𝑎 𝐽 𝑠 + 𝐷𝑚 + 𝐾𝑏 𝑠𝜃𝑚 𝑠 = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑠) 𝐾𝑡 𝑚 TF: 𝑲𝒕 𝑮 𝒔 = 𝜽𝒎 (𝒔) (𝑹𝒂 𝑱𝒎 ) = 𝑬𝒂 (𝒔) 𝒔 𝒔 + 𝟏 𝑫 + 𝑲𝒕 𝑲𝒃 𝑱𝒎 𝒎 𝑹𝒂 This equation can be expressed as 𝜃𝑚 (𝑠) 𝐾 = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑠) 𝑠(𝑠 + 𝛼) with 𝐾 = 𝐾𝑡 (𝑅𝑎 𝐽𝑚 ) 𝛼= 1 𝐽𝑚 𝐷𝑚 + How to determine the constant parameters? 𝐾𝑡 𝐾𝑏 𝑅𝑎 18 Mechanical constants 𝐽𝑚 and 𝐷𝑚 . Consider a motor with inertia 𝐽𝑎 and damping 𝐷𝑎 at the armature driving a load consisting of inertia 𝐽𝐿 and damping 𝐷𝐿 . 𝐽𝐿 and 𝐷𝐿 can be reflected back to the armature as some equivalent inertia and damping ratio to be added to 𝐽𝑎 and 𝐷𝑎 respectively. Thus the equivalent inertia 𝐽𝑚 and equivalent damping 𝐷𝑚 at the armature are 𝐽𝑚 = 𝐽𝑎 + 𝑁1 2 𝐽𝐿 ; 𝑁2 𝐷𝑚 = 𝐷𝑎 + 𝑁1 2 𝐷𝐿 𝑁2 Electrical constants. Substituting (a) and (c) to (b) with 𝐿𝑎 = 0 gives 𝑅𝑎 𝑇 𝑠 + 𝐾𝑏 𝑠𝜃𝑚 𝑠 = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑠) 𝐾𝑡 𝑚 By the inverse Laplace transform, we get 19 𝑅𝑎 𝑑𝜃𝑚 (𝑡) 𝑇𝑚 𝑡 + 𝐾𝑏 = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑡) 𝐾𝑡 𝑑𝑡 𝑅𝑎 𝑇 𝑡 + 𝐾𝑏 𝜔𝑚 (𝑡) = 𝑒𝑎 (𝑡) 𝐾𝑡 𝑚 If a dc voltage 𝑒𝑎 is applied, the motor will turn at a constant angular velocity 𝜔𝑚 with a constant torque 𝑇𝑚 . So when a motor is operating at a steady state with a dc input, 𝑅𝑎 𝑇𝑚 + 𝐾𝑏 𝜔𝑚 = 𝑒𝑎 𝐾𝑡 Torque – speed curve or 𝐾𝑏 𝐾𝑡 𝐾𝑡 𝑇𝑚 = − 𝜔 + 𝑒 𝑅𝑎 𝑚 𝑅𝑎 𝑎 𝐾𝑡 𝑲𝒕 𝑻𝒔𝒕𝒂𝒍𝒍 𝑇𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑙 = 𝑒 → = 𝑅𝑎 𝑎 𝑹𝒂 𝑹𝒂 𝑒𝑎 𝒆𝒂 𝜔𝑛𝑜−𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑑 = → 𝑲𝒃 = 𝐾𝑏 𝝎𝒏𝒐−𝒍𝒐𝒂𝒅 A dynamometer test of the motor would yield 𝑇𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑙 and 𝜔𝑛𝑜−𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑑 for a given 𝑒𝑎 . 20 Ex.: Given the system and torque-speed curve (a) and (b), find the TF 𝜃𝐿 𝑠 𝐸𝑎 𝑠 . Mechanical constants 𝐽𝑚 and 𝐷𝑚 𝐽𝑚 = 𝐽𝑎 + 𝐽𝐿 𝑁1 𝑁2 2 1 = 5 + 700 10 Electrical constants From the curve: 𝐾𝑡 𝑅𝑎 2 = 12 𝐷𝑚 = 𝐷𝑎 + 𝐷𝐿 𝑁1 𝑁2 2 1 = 2 + 800 10 2 = 10 𝐾𝑡 , 𝐾𝑏 𝑅𝑎 = 𝑇𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑙 𝑒𝑎 = 500 100 = 5 and 𝐾𝑏 = 𝑒𝑎 𝜔𝑛𝑜−𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑑 = 100 50 =2 21 Then 𝐾𝑡 𝜃𝑚 (𝑠) (𝑅𝑎 𝐽𝑚 ) = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑠) 𝑠 𝑠 + 1 𝐷 + 𝐾𝑡 𝐾𝑏 𝐽𝑚 𝑚 𝑅𝑎 We know that 𝑁1 𝑁2 = 1 , 10 5 = 𝑠 𝑠+ 12 1 10 + (5)(2) 12 0.417 = 𝑠(𝑠 + 1.667) so the TF: 𝜃𝐿 (𝑠) 0.0417 = 𝐸𝑎 (𝑠) 𝑠(𝑠 + 1.667) 22 HW • Problems no. 33 and 44 Chapter 2 [Nise] 23