Uploaded by

common.user23851

Men’s Experiences in Domestic Violence Counseling Program: Yogyakarta, Indonesia

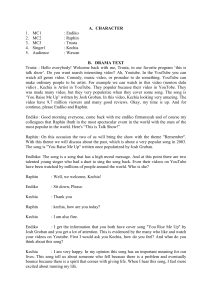

advertisement