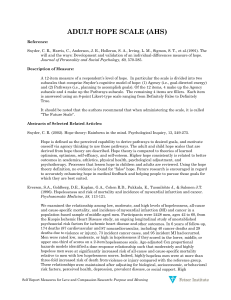

Validity Studies The Ways of Coping Scale A Reliability Generalization Study Educational and Psychological Measurement Volume 68 Number 2 April 2008 262-280 Ó 2008 Sage Publications 10.1177/0013164407310128 http://epm.sagepub.com hosted at http://online.sagepub.com Kathryn R. Rexrode Philhaven Behavioral Healthcare Services Suni Petersen Siobhan O’Toole Alliant International University For more than 20 years, the Ways of Coping Scale (WOCS) has been used extensively to measure coping. Yet beyond the original psychometric data, few studies have reexamined its properties utilizing the enormous body of research generated on the WOCS. Reliability has been assumed to be consistent as an attribute of the test. This study used reliability generalization to identify (a) the variability in reliability estimates for the WOCS scores across studies, (b) the typical score reliability for the WOCS, and (c) the salient features across studies that relate to the variability in reliability estimate scores for the WOCS. Typical reliability across subscale scores ranged from .60 to .75 with Positive Reappraisal showing the least variability and Self-Controlling showing the most. Factors related to this variability were age and format of administration. Keywords: Ways of Coping Scale; reliability generalization; reliability; reliability coefficients; coping measures S cores are reliable, not measures (Vacha-Haase, 1998), making statements about the reliability of a measure inappropriate and potentially misleading (Pedhazur & Schmelkin, 1991). Using test manuals or prior studies to determine the reliability of measures for a proposed study is risky. Reliability is affected by variability in sample characteristics and successive administrations of an instrument. Unreliable scores can lead to attenuation of the reported effect size (Reinhardt, 1996) and affect statistical power (Onwuegbuzie & Daniel, 2002). Recently, reliability generalization has been used as a method to determine the reliability likely to be achieved by a particular instrument given certain sample or instrument characteristics (Henson, Kogan, & Vacha-Haase, 2001). Many areas of psychological research focus on coping as an important variable, yet the investigation of psychometric properties have not kept pace with the proliferation Authors’ Note: The authors thank Dr. Lois Benishek and Pilar Gonzalez for their assistance with data collection and Todd Snyder for his assistance with coding. Please address correspondence to Kathryn Rexrode, Philhaven Behavioral Healthcare Services, 283 South Butler Road, P.O. Box 550, Mount Gretna, PA 17064; e-mail: [email protected]. 262 Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability 263 of studies. Relying on its popularity, researchers have placed an enormous amount of confidence in the most popular instrument of coping, the Ways of Coping Scale (WOCS; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988b). This article discusses the theoretical basis and properties of the WOCS, reports on reliability generalization results, and makes recommendations for its use in future studies. Coping as a Construct Some researchers view coping as an ego state (Vaillant, 1977), others as stable personality traits (Costa & McCrae, 1989), and still other researchers focus on coping as a transactional process (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980; Lazarus, 1993). Each conceptualization has limitations. Although a thorough discussion of models of coping are beyond the scope of this article, it is essential to provide an overview of the conceptualization of coping underlying the WOCS. Beginning in the 1970s, Richard Lazarus developed the cognitive phenomenological theory of stress, which incorporates a transactional explanation of the stress process (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). There are three types of stress: challenge, threat, and harm-loss (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Challenge involves potentially gaining something by overcoming obstacles through mastery. Whereas threat occurs when someone anticipates potential harm-loss, harm-loss is the actual loss of something. During a stressful encounter, an individual makes appraisals of the particular situation (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). First, the person conducts a primary appraisal to evaluate what is at stake in the situation and then engages in a secondary appraisal to assess his or her coping resources and alternatives to manage the situation. Once coping efforts affect or do not affect the stressful encounter, new appraisals are made and new coping efforts are ensued. When stress occurs, individuals cope by using cognitive or behavioral strategies to deal with internal and external demands as well as conflicts between these two things (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Typically, they are either problem focused or emotion focused. Whereas problem-focused coping alters the source of stress in the person–environment relationship, emotion-focused coping serves to decrease distressful emotions. Measurement of Coping Instruments used to measure the coping construct are plagued with psychometric problems (De Ridder, 1997). Issues surrounding such problems include whether coping is a process or style, the various dimensions of coping, and the validity and reliability of scores from coping scales (De Ridder, 1997; Stone, Kennedy-Moore, Newman, Greenberg, & Neale, 1992). Although many researchers agree that coping is a process and varies depending on the situation, researchers frequently Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 264 Educational and Psychological Measurement conduct their research in a way that suggests that people have consistent ways of coping that they use in practically all situations (De Ridder, 1997). Another problem with the current realm of coping research involves the large number of identified coping responses. To reduce this number, coping responses have been categorized into various dimensions, a term that is conceptually problematic as a result of researchers failing to distinguish between coping strategies (i.e., distancing and positive reappraisal) and metastrategies that are groups of strategies (i.e., approach and avoidance coping; De Ridder, 1997). Some researchers contend that only behavioral responses constitute coping. Others challenge this thinking by stating that cognitions are a form of coping as well (De Ridder, 1997). The WOCS The WOCS is one of the most widely used coping measures to date (De Ridder, 1997; Parker & Endler, 1992; Stone et al., 1992). The WOCS reflects transactional theory in several ways (Stone et al., 1992). It is meant to be used with a specific stressful encounter in mind, measuring what a person actually does in that situation rather than what he or she typically does or thinks he or she should do. The person is expected to report all coping efforts, not just those that were helpful. The measure categorizes multiple dimensions of coping into either emotion-focused or problemfocused efforts. According to the manual, the WOCS asks respondents to think of the most stressful event that has occurred in the past week, to write a description of it, and to identify all of the coping responses used to deal with the situation. The manual, however, allows the reader to determine certain aspects of administration. For example, some researchers use elaborate interviewing techniques to assist the participant in focusing on an event whereas others simply use self-administration and open-ended referent events (Charlton & Thompson, 1996; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988b; Miller, Gordon, Daniele, & Diller, 1992). Both the way at arriving at the trigger event and the process of administration can be modified. Although the manual designates a 1-week time frame, researchers have varied this feature from proximal to distal events. This flexibility is one of the advantages of the WOCS; however, it also makes it susceptible to changes that may compromise the reliability of scores, particularly in the absence of examining the impact of such deviations. Thus, this study tested bona fide adaptations to compare reliabilities. Adaptations include version of test, Likert scale (4 or 5 points), format (self-report, interview), recall time window, target stressor, translation, gender, ethnicity, age, and population type (clinical, nonclinical, medical). The wide variability in WOCS reliability scores could be due to the leeway afforded the researcher. It is also possible that the variability in reliability estimates may be due to the instability of the factor structure across populations and settings. Parker, Endler, and Bagby (1993) conducted a confirmatory factor analysis in two Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability 265 studies with college students. Results yielded the following factors: Distancing/ Avoidance, Confrontive/Seeking Social Support, Problem Focused, and Denial. Edwards and O’Neill (1998) conducted another confirmatory factor analyses. Unfortunately, they found little support for the 1988 factor structure, which they attributed to a lack of domain sampling procedures. Smyth and Yarandi (1996) conducted a factor analysis using African American workers and found that Active Coping, Avoidance, and Minimizing the Situation accounted for 67% of the variance. Instead of constructing items based on a priori constructs, the items on the WOCS appeared to be gathered because they were related to a particular coping strategy, which may never result in a stable and meaningful factor structure. Such differences in factor structures could also account for the variability in reliability. Reliability Generalization Reliability induction refers to researchers’ use of reliability coefficients from the manual or other studies (Vacha-Haase, Henson, & Caruso, 2002). Such reliability induction occurs frequently in scientific articles because authors fail to report reliability coefficients for their particular sample (Shields & Caruso, 2004; VacheHaase, Ness, Nilsson, & Reetz, 1999). Reliability generalization is a method used to determine the factors that relate to the reliability of scores across studies by calculating the mean measurement error variances and exploring factors related to such score error variance (Vacha-Haase, 1998). Reliability generalization can identify both the typical score reliability and the variability in reliability estimates for an instrument across studies. The value of the method lies in its ability to identify how and why score reliability varies across studies for a particular instrument (Yin & Fan, 2000). The purpose of this study was to examine the reliability generalization of the WOCS. Method Archival Data Collection Three sets of literature searches were completed (i.e., February 2001, targeting a time window of 1986-2001; May 2002, targeting a time window of 2000-2002; and June 2004, targeting a time window of 2002-2004). Five databases (PsycINFO, LexusNexus, Web of Science, Medline, and PsycARTICLES) were searched. The reference sections from the articles were scanned for other potential articles that used the WOCS. The search criterion was any article that gave one of six versions of the WOCS to participants. The researchers eliminated articles that were duplicated in different databases, written in non-English language, or used a modification of the WOCS that did not comply with any of the published and validated versions. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 266 Educational and Psychological Measurement Then we categorized the articles into (a) articles reporting coefficient alpha estimates for the eight subscales of the WOCS, (b) articles reporting less than the possible eight coefficient alpha estimates, (c) articles citing coefficient alpha estimates from another source/article, and (d) articles reporting no coefficient alpha estimates. Authors of articles were contacted to obtain the coefficient alpha estimates in cases where alphas were not reported for current scores on each of the eight subscales. Coding of Article Characteristics A template was developed to code the key characteristics associated with each study. Variables were dummy coded as needed. Coding resulted in 93.33% agreement between two independent raters. Remaining discrepancies were the product of oversight and were resolved. Predictor variables were coded as follows: type of article (substantive or measurement), version (1988/1986 Folkman–Vitaliano–LaPoint– Folkman variation, or cancer version collapsed to 1988/1986 Folkman, or other), Likert scale (4 or 5 points); format (self-report or interview), recall time window (past week, past 2 weeks, past month, past 6 months, past year, future, or other collapsed to past week/current or all others), target stressor (self-selected, vocational academic, caregiving relationship, physical compromise, or other collapsed to selfselected, vocational/academic, caregiving relationship, or physical compromise), translation (English, non-English, or combination collapsed to English or other), gender (mixed, female, or male samples collapsed to mixed gender or one gender), ethnicity (mixed, all White, all Black, or international collapsed to national or international), sample source (adolescents, college age, adults, seniors, or mixed collapsed to adults only or other), and population type (nonclinical, medically compromised, psychopathological, cancer, or mixed collapsed to nonclinical or other). Data Analysis: Data Reduction Phase Given that the sample size of coefficient alpha estimates were small and varied depending on the subscale (i.e., Confrontive Coping [CC] = 80, Distancing [D] = 83, Self-Controlling [SC] = 83, Seeking Social Support [SS] = 106, Accepting Responsibility [AR] = 78, Escape-Avoidance [EA] = 86, Planful Problem Solving [PP] = 83, and Positive Reappraisal [PR] = 81), the number of levels for the predictor variables were collapsed as noted above to increase the sample size within each level. Levels within variables that contained less than 15% of the sample or were conceptually related were collapsed. For example, the time recall window consisted of seven levels. The percentage of data points associated with each of these levels was 68.8%, 1.8%, 4.5%, 1.8%, 0%, 0%, and 16.1%, respectively. These seven categories were then collapsed into two categories (i.e., past week/current and other), Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability 267 with 68.8% and 24.1% of the data, respectively. Any two-level predictors that had statistically significant differences in percentages were deleted because a significant imbalance in the distribution of data would not have been an accurate representation of the category and may not have allowed any differences to be found. After using these procedures, the 10 variables retained were version, format, recall time window, target stressor, translation, sample size, sample gender, sample ethnicity, sample source, and population type. Results Reliability Induction and Range of Coefficients This study of the WOCS confirmed that although some researchers report reliability coefficient estimates for their sample and data, others continue to use reliability induction as evidence that their data are reliable. Of the 661 citations found during the data collection process, 92 were usable. Because some articles provided reliability estimates for multiple samples, the 92 articles yielded 112 data points for this study. Of the 92 articles, 23% of the authors had to be contacted for coefficient alpha estimates. Another 16% (n = 15) of the articles reported reliability coefficient estimates from the WOCS manual or previous research studies and also had to be contacted. In all, before any authors were contacted, 36 of the 92 articles (39%) failed to report reliability estimate information for the sample data. Figure 1 presents box and whiskers plots to display the variability across scale reliability coefficients and to determine typical reliability for each scale of the WOCS. Predictors of Reliability Estimates ANOVAs were used to identify variables that predicted reliability estimates for the different subscales. Version, sample gender, and population type were not statistically significantly related to reliability estimates for any subscales. Four variables were statistically significantly related to only a single subscale. Recall time window predicted the AR subscale, F(1, 69) = 4.75, p < :05, Z2 = :06, with current/past week demonstrating lower reliability estimates. Format was statistically significant only for the EA subscale, F(1, 83) = 4.87, p < :05, Z2 = :06. Self-report format produced higher reliability estimates than interviews. Translation was statistically significant only for the SC subscale, F(1, 80) = 6.18, p < :05, Z2 = :07, with higher coefficient alphas related to the English version. Overall, there was a statistically significant difference in reliability estimates for the SS subscale across target stressor, F(3, 93) = 3.12, p < :05, Z2 = :09. Utilizing a Scheffé post hoc comparison, the only statistically significant difference was between caregiving/relationship and physical compromise (p < :05), with the caregiving/ relationship category related to higher coefficient alpha levels. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 268 Educational and Psychological Measurement Figure 1 Box and Whisker Plot of Subscale Reliability Coefficients Note: Outliers (O) are values more than 1.5 box lengths from the 25th percentile, and extremes (∗ ) are values more than 3 box lengths from the 25th percentile. AR = Accepting Responsibility; CC = Confrontive Coping; D = Distancing; EA = Escape-Avoidance; PP = Planful Problem Solving; PR = Positive Reappraisal; SC = Self-Controlling; SS = Seeking Social Support. Sample source and sample ethnicity were predictive of reliability estimates for more than one subscale. Sample source was statistically significant for AR, F(1, 76) = 6.24, p < :05, Z2 = :08; PR, F(1, 79) = 14.15, p < :001, Z2 = :15; and SC, F(1, 80) = 7.40, p < :01, Z2 = :09. For each of these subscales, an all adult sample source produced higher coefficient alpha levels than other samples. Sample ethnicity reached statistical significance for PR, F(1, 60) = 12.55, p < :001, Z2 = :17, and SC, F(1, 62) = 6.11, p < :05, Z2 = :09. For both the PR and SC subscales, a U.S.-based sample was predictive of higher reliability estimates than an international sample. Tables 1 through 5 provide details for the ANOVAs. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability 269 Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and One-Way ANOVAs for Effects of Translation on WOCS Subscale Score Coefficient Alpha Estimates Translated English ANOVA Variable M SD M SD df F Z2 AR CC D EA PP PR SC SS .60 .59 .60 .66 .71 .72 .55 .75 .13 .14 .17 .09 .06 .08 .18 .06 .63 .62 .65 .70 .70 .76 .65 .74 .12 .12 .12 .09 .08 .08 .11 .08 1, 74 1, 76 1, 79 1, 82 1, 79 1, 77 1, 79 1,102 0.80 0.21 1.91 2.55 0.08 3.19 6.18∗ 0.26 .01 .00 .02 .03 .00 .04 .07 .00 Note: WOCS = Ways of Coping Scale; ANOVA = analysis of variance; Z2 = partial eta-squared estimated effect size; AR = Accepting Responsibility; CC = Confrontive Coping; D = Distancing; EA = Escape-Avoidance; PP = Planful Problem Solving; PR = Positive Reappraisal; SC = SelfControlling; SS = Seeking Social Support. ∗ p < .05. Table 2 Means, Standard Deviations, and One-Way ANOVAs for Effects of Recall Time Window on WOCS Subscale Score Coefficient Alpha Estimates Current/Past Week Other ANOVA Variable M SD M SD df F Z2 AR CC D EA PP PR SC SS .61 .61 .64 .70 .70 .76 .62 .74 .12 .12 .12 .08 .08 .07 .13 .07 .68 .62 .63 .69 .72 .73 .65 .75 .09 .14 .16 .11 .08 .09 .13 .09 1, 69 1, 72 1, 75 1, 77 1, 75 1, 73 1, 75 1, 96 4.75∗ 0.10 0.08 0.30 0.82 3.45 0.83 0.77 .06 .00 .00 .00 .01 .05 .01 .01 Note: See note to Table 1. ∗ p < .05. Finally, a set of Pearson product–moment correlations were used to assess whether sample size was related to the reliability estimates of any of the subscale scores. The correlations ranged from r = −.15 (p > .05) for the SC subscale to r = :04 (p > .05) for the D subscale. Sample size was not a statistically significant predictor of coefficient alpha estimates for any of the subscale scores. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 270 Educational and Psychological Measurement Table 3 Means, Standard Deviations, and One-Way ANOVAs for Effects of Format on WOCS Subscale Score Coefficient Alpha Estimates Self-Report Interview ANOVA Variable M SD M SD df F Z2 AR CC D EA PP PR SC SS .63 .62 .64 .71 .71 .75 .63 .74 .12 .12 .13 .09 .08 .08 .13 .07 .60 .55 .60 .65 .68 .74 .61 .75 .13 .14 .12 .05 .07 .08 .10 .10 1, 75 1, 78 1, 81 1, 83 1, 81 1, 79 1, 81 1, 103 0.38 2.34 1.09 4.87∗ 0.96 0.24 0.28 0.06 .01 .03 .01 .06 .01 .00 .00 .00 Note: See note to Table 1. ∗ p < .05. Table 4 Means, Standard Deviations, and One-Way ANOVAs for Effects of Sample Ethnicity on WOCS Subscale Score Coefficient Alpha Estimates International United States ANOVA Variable M SD M SD df F Z2 AR CC D EA PP PR SC SS .62 .60 .63 .67 .70 .71 .58 .75 .13 .13 .16 .09 .07 .08 .16 .07 .62 .62 .65 .71 .70 .78 .67 .74 .14 .13 .14 .08 .10 .08 .12 .09 1, 57 1, 59 1, 61 1, 62 1, 60 1, 60 1, 62 1, 74 0.01 0.27 0.16 2.46 0.03 12.56∗∗∗ 6.11∗ 0.39 .00 .01 .00 .04 .00 .17 .09 .01 Note: See note to Table 1. ∗ p < .05. ∗∗∗ p < .001. Discussion The purpose of this reliability generalization study was to identify (a) the amount of variability in reliability estimate scores for the WOCS subscales, (b) the typical reliability of scores for the subscales, and (c) the instrument and sample-related characteristics that are related to the reliability of scores that are obtained on the WOCS. Only 61% of the WOCS articles used in this study attributed reliability to the scores Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability 271 Table 5 Means, Standard Deviations, and One-Way ANOVAs for Effects of Sample Source (Age Group) on WOCS Subscale Score Coefficient Alpha Estimates Adults Other ANOVA Variable M SD M SD df F Z2 AR CC D EA PP PR SC SS .64 .62 .65 .71 .70 .77 .65 .75 .11 .13 .13 .08 .09 .08 .12 .08 .57 .57 .60 .67 .69 .69 .57 .72 .15 .11 .12 .10 .07 .06 .09 .08 1, 76 1, 77 1, 81 1, 83 1, 80 1, 79 1, 80 1, 103 6.24∗ 2.50 1.68 2.85 0.31 14.15∗∗∗ 7.40∗∗ 3.03 .08 .03 .02 .03 .00 .15 .09 .03 Note: See note to Table 1. ∗ p < .05. ∗∗ p < .01. ∗∗∗ p < .001. rather than the actual instrument, and another 39% of the studies did not report reliability. The range of reliability coefficients across studies was dramatic. This study demonstrates the dire need for emphasizing to researchers the importance of reporting reliability for their particular samples and supporting the recent initiatives to standardize research reporting. Clearly, there are no fixed reliability coefficient estimates for the WOCS subscales. Characteristics Related to Reliability A few of the instrument and sample-related characteristics examined in this reliability generalization study explained a moderate proportion of the variance in coefficient reliability estimates (AR, PR, and SC subscales), and these variances were influenced by different factors. In analyzing data from the WOCS, researchers might consider those factors that should be statistically controlled in order to ensure reliability of the WOCS with their sample. AR subscale. The AR subscale refers to acknowledging one’s own role in the problem with a concomitant theme for trying to put things right. The standard administration method calls for a time window within 1 week, but the results of this study suggest that for this subscale a greater time window leads to higher reliability coefficients. With stressors, a person often goes through a reactive process that includes shock, anger, denial, or sadness, which may last longer with the increasing severity of the stressor (Courtois, 2004) and make it premature for a person to examine his or her own role and take responsibility for that role within a 1-week Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 272 Educational and Psychological Measurement time window. Furthermore, coping may vary week to week for extraneous reasons. Consequently, a larger time window affords the opportunity to engage in more strategies and observe one’s own process. PR subscale. The PR subscale ‘‘describes efforts to create positive meaning by focusing on personal growth’’ (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988b, p. 11). The age of participants was a statistically significant predictor with greater reliability when used with adults than when used with younger age groups. Children have less time in their lives to build a repertoire of coping skills. Their expressions of distress are much more likely to be unfocused than adults’ (McCown & Davies, 1995) and dependent on the quality of caregiving (Broderick & Blewitt, 2006). At the same time, there is more danger of a shift in attachment to the parents during times of severe family stress (Broderick & Blewitt, 2006) as parents struggle to maintain their own equilibrium. In the absence of guidance and a possible shift in attachment, children’s distress is sometimes stalled and emerges in behavioral problems that appear unrelated to the stressor (Worden, Davies, & McCown, 1999). Adolescents and college students may encompass a wider spread of moral development and developmental stages leading to a more heterogeneous group than adults. Adults may have a more practiced repertoire of coping skills and as a result are more likely to focus on personal growth as a goal and source of pride in dealing with distress. In so doing, adults may have more of a tendency than younger individuals to reframe stressful situations (Faust & Katchen, 2004; Shelby, 1997). Another possibility that may account for these population differences is that the PR subscale contains a spiritual dimension (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988b), and as people age, they increasingly use spirituality as a form of coping (Martin, Rott, Poon, Courtenay, & Lehr, 2001). Therefore, it is likely that the WOCS will result in more reliable scores when the PR scale is administered to adults than to younger people. The study began with assessing ethnicity (meaning racial identification, immigrant identification, and different nationalities). Reliabilities were rarely reported on different ethnic groups. Therefore, these categories were collapsed into one, and because it was predominantly international, this designation was juxtaposed with national. Therefore, as the scale is used on larger diverse samples, differential statistical analyses should be conducted. SC subscale. The SC subscale of the WOCS describes ‘‘efforts to regulate one’s feelings and actions’’ (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988b, p. 11). Factors predicting reliability for the SC subscale were source and translation. However, of the predictors, age of participants was the only statistically significant predictor, again with adults producing scores with higher reliability. Young people tend to decrease impulsivity and increase self-control as they move toward adulthood (Greene et al., 2000). The prediction models included factors that were not statistically significant yet did account for a portion of the variance. This outcome could be explained by the lack of reporting in many articles. Gender also accounted for variance, yet most Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability 273 studies included both genders without analyzing reliabilities independently for each. The few studies that included only women or only men showed more variability; therefore, it is likely that there are differences based on gender. Again, it would be extremely beneficial for researchers to conduct independent reliability analyses on segments of their sample. EA subscale. The EA subscale ‘‘describes wishful thinking and behavioral efforts to escape or avoid the problem’’ (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988b, p. 11). The reliability of the WOCS on the EA subscale appears to be sensitive to the administration format. Greater reliability will be achieved on this scale with self-report rather than interview, which may be due to the sensitive nature of some of the questions, such as use of substances. SS subscale. The targeted stressor was related to the reliability variance on the SS subscale. Although social support is a factor in the adjustment to many situations, there are some situations in which social support may not be as necessary. With serious illness, a person’s tendency to seek social support diminishes in order to accommodate the physical demands of the illness. When faced with disasters that have compromised basic needs, practical support is far more important than social support (Massey, 1997). The remaining WOCS subscales. Based on the results of this study, reliabilities on CC, D, and PP were not predicted by any of the variables in this study and therefore are less likely to be compromised with different populations or ways of administering the WOCS. Recommendations for the Use of the WOCS There are multiple recommendations regarding the use of the WOCS. First, researchers need to report reliability estimates, paying particular attention to attributing the reliability statistics to their sample scores. Calculating reliability coefficients separately for gender, ethnicity, and age groups will make a considerable contribution to the literature. Researchers should go beyond reporting reliability coefficients by addressing the effect on resulting reliabilities in their interpretation of results (Vacche-Hasse et al., 2002). Second, researchers should more adequately describe their samples. Third, it is recommended that researchers use a time window greater than 1 week for the AR subscale. Fourth, samples should be limited to adults or controlled for age with the AR, SC, and PR subscales. Fifth, until further information is gleaned through future studies, it may be helpful for researchers to use the standardized approach via the manual to administer the WOCS because, in our study, many researchers deviated from scale administration instructions. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 274 Educational and Psychological Measurement Limitations of the Study and Directions for Future Research The major limitation of this study is the fact that it is underpowered for a complete exploration of the variables related to the reliability scores, which was due to the underreporting and misreporting problems cited previously. Some researchers have proposed that the lack of reporting of sample reliability estimates is due to the ‘‘file drawer’’ problem of not publishing studies with low reliabilities (Shields & Caruso, 2003, p. 410). Other researchers who find that their reliability estimates are too low may opt not to report the statistics or may report reliability estimates from the manual. Therefore, possible studies with low reliability were not likely a part of the sample of data used in this study. There was also an underreporting of the predictor variables investigated. Test-retest reliability was intentionally excluded from analysis in this study for reasons other than the lack of data. Folkman and Lazarus (1988b) state that testretest reliability is in direct conflict with their transactional theory of stress. Healthy individuals make adjustments in coping as time passes, and such changes render test-retest reliabilities meaningless. The standard deviation of scores is another frequently coded variable in reliability generalization studies (Caruso, Witkiewwitz, Belcourt-Dittloff, & Gottlieb, 2001). It is fairly well known that higher variance in scores is related to higher reliability (Crocker & Algina, 1986; Kieffer & Reese, 2002). Based on classical test theory, ‘‘if error variance remains constant and observed score variance increases, then true score variance must increase to exactly the same extent’’ (Shields & Caruso, 2003, p. 409). Reliability, which is the ratio of true variance to total variance, will also increase as a result. Unfortunately, the standard deviation of scores is not always reported by researchers in the literature. Many articles described their participants by source of sample (such as college students) without reporting age; therefore, the study did not discriminate between ages but rather between broad categories of people. It would be helpful to specify specific age ranges of both adults and young people (Martin et al., 2001). In summary, the results suggest that the reliability of the WOCS varies based on subscales, administration, and sample variables. Reporting problems have led to a misunderstanding of where, when, and with whom to use this instrument. This situation is likely to improve as researchers heed Wilkinson and the American Psychological Association Task Force on Statistical Inference’s (1999) recommendation that all researchers report reliability coefficient estimate information for their sample data, even if the study is not a psychometric study (Henson & Thompson, 2002). The WOCS has more data gathered than any other coping instrument. Although it was originally developed using solid test construction strategies, the ongoing investigatory work has been limited. Future research should focus on strengthening the instrument and understanding the factors related to obtaining adequate reliability across studies. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability 275 Most important, researchers using the instrument should report more specific population descriptions, means, standard deviations, and reliabilities on each subscale. References References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis. ∗ Afari, N., Schmaling, K. B., Herrell, R., Hartman, S., Goldberg, J., & Buchwald, D. S. (2000). Coping strategies in twins with chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 48, 547-554. ∗ Ahlstrom, G., & Wenneberg, S. (2002). Coping with illness-related problems in persons with progressive muscular diseases: The Swedish Version of the Ways of Coping Scale. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 16, 368-375. ∗ Azar, R., & Solomon, C. R. (2001). Coping strategies of parents facing child diabetes mellitus. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 16, 418-428. ∗ Badger, T. A. (1992). Coping, life-style changes, health perceptions, and marital adjustment in middleaged women and men with cardiovascular disease and their spouses. Health Care for Women International, 13, 43-55. ∗ Bardwell, W. A., Ancoli-Israel, S., & Dimsdale, J. E. (2001). Types of coping strategies are associated with increased depressive symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. SLEEP, 24, 905-909. ∗ Benotsch, E. G., Brailey, K., Vasterling, J. J., Uddo, M., Constans, J. I., & Sutker, P. B. (2000). War zone stress, personal and environmental resources, and PTSD symptoms in Gulf War veterans: A longitudinal perspective. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 205-213. ∗ Berntsson, L., & Ringsberg, K. C. (2003). Correlation between perceived symptoms, self-rated health and coping strategies in patients with asthma-like symptoms but negative asthma tests. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 8, 305-315. ∗ Billings, D. W., Folkman, S., Acree, M., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Coping and physical health during care giving: The roles of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 131-142. ∗ Blake, D. D., Cook, J. D., & Keane, T. M. (1992). Post-traumatic stress disorder and coping in veterans who are seeking medical treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 48, 695-704. ∗ Blankstein, K. R., Flett, G. L., & Watson, M. S. (1992). Academic problem-solving ability in test anxiety. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 48, 37-46. ∗ Bouchard, G., Lussier, Y., Wright, J., & Richer, C. (1998). Predictive validity of coping strategies on marital satisfaction: Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Family Psychology, 12, 112-131. ∗ Bramsen, I., Bleiker, E. M. A., Triemstra, A. H. M., Van Rossum, S. M. G., & Van Der Ploeg, H. M. (1995). A Dutch adaptation of the Ways of Coping Scale: Factor structure and psychometric properties. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 8, 337-352. ∗ Brantley, P. J., O’Hea, E. L., Jones, G., & Mehan, D. J. (2002). The influence of income level and ethnicity on coping strategies. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 24, 39-45. Broderick, P., & Blewitt, P. (2006). The life span: Human development for helping professionals (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. Caruso, J. C., Witkiewwitz, K., Belcourt-Dittloff, A., & Gottlieb, J. D. (2001). Reliability of scores from the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire: A reliability generalization study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61, 675-689. ∗ Chan, D. W. (1994). The Chinese Ways of Coping Scale: Assessing coping in secondary school teachers and students in Hong Kong. Psychological Assessment, 6, 108-116. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 276 Educational and Psychological Measurement ∗ Chang, C., Lee. L., Connor, K., Davidson, J. R. T., Jeffries, K. H., & Lai, T. (2003). Posttraumatic distress and coping strategies among rescue workers after an earthquake. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191, 391-398. ∗ Charlton, P. F. C., & Thompson, J. A. (1996). Ways of coping with psychological distress after trauma. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 517-530. ∗ Chou, K., LaMontagne, L., & Hepworth, J. T. (1999). Burden experienced by caregivers of relatives with dementia in Taiwan. Nursing Research, 48, 206-214. ∗ Christensen, A. J., Benotsch, E. G., Lawton, W. J., & Wiebe, J. S. (1995). Coping with treatmentrelated stress: Effects on patient adherence in hemodialysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 454-459. ∗ Christensen, A. J., Moran, P. J., Stallman, D., Voigts, A. L., & Lawton, W. J. (1997). Monitoring attentional style and medical regimen adherence in hemodialysis patients. Health Psychology, 16, 256-262. ∗ Chung, M. C., Easthope, Y., Chung, C., & Clark-Carter, D. (2001a). Traumatic stress and coping strategies in sesternary victims following an aircraft disaster in Conventry. Stress and Health, 17, 67-75. ∗ Chung, M. C., Farmer, S., Grant, K., Newton, R., Payne, S., Perry, M., et al. (2003). Coping with posttraumatic stress symptoms following relationship dissolution. Stress and Health, 19, 27-36. ∗ Chung, M. C., Farmer, S., Werrett, J., Easthope, Y., & Chung, C. (2001b). Traumatic stress and ways of coping of community residents exposed to a train disaster. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 528-534. ∗ Collins, F. E., & French, C. H. (1998). Dissociation, coping strategies, and locus of control in a nonclinical population: Clinical implications. Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 26, 113-126. Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1989). Personality, stress, and coping: Some lessons from a decade of research. In P. T. Costa & R. R. McCrae (Eds.), Aging, stress, and health (pp. 269-285). Chichester, NY: John Wiley. Courtois, C. (2004). Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, and Training, 41, 412-425. Crocker, L., & Algina, J. (1986). Introduction to classical and modern test theory. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ∗ Daus, C. S., & Joplin, J. R. W. (1999). Survival of the fittest: Implications of self-reliance and coping for leaders and team performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4, 15-28. De Ridder, D. (1997). What is wrong with coping assessment? A review of conceptual and methodological issues. Psychology and Health, 12, 417-431. ∗ Dropkin, M. J. (2001). Anxiety, coping strategies, and coping behaviors in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer Nursing, 24, 143-148. ∗ Dyck, D. G., Short, R., & Vitaliano, P. P. (1999). Predictors of burden and infectious illness in schizophrenia caregivers. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61, 411-419. ∗ Eagen, A. E., & Walsh, W. B. (1995). Person-environment congruence and coping strategies. Career Development Quarterly, 43, 246-256. ∗ Edwards, J. R., & Baglioni, A. J. (1993). The measurement of coping with stress: Construct validity of the Ways of Coping Checklist and the Cybernetic Coping Scale. Work & Stress, 7, 17-31. Edwards, J. R., & O’Neill, R. M. (1998). The construct validity of scores on the Ways of Coping Questionnaire: Confirmatory analysis of alternative factor structures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58, 955-983. Faust, J., & Katchen, L. B. (2004). Treatment of children with complicated post traumatic stress reactions. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, & Training, 41, 426-437. ∗ Folkman, S., Chesney, M. A., & Christopher-Richards, A. (1994). Stress and coping in caregiving partners of men with AIDS. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 17, 35-53. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability ∗ 277 Folkman, S., Chesney, M. A., Cooke, M., Boccellari, A., & Collette, L. (1994). Caregiver burden in HIV-positive and HIV-negative partners of men with AIDS. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 746-756. Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219-239. ∗ Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988a). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 466-475. Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988b). Manual for the Ways of Coping Scale. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychology Press. ∗ Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 992-1003. ∗ Ghaderi, A., & Scott, B. (2000). Coping in dieting and eating disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188, 273-279. ∗ Ghaderi, A., & Scott. B. (2003). Pure and guided self-help for full and sub-threshold bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42, 257-269. ∗ Giese-Davis, J., Hermanson, K., Koopman, C., Weibel, D., & Spiegel, D. (2000). Quality of couples’ relationship and adjustment to metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 251-266. ∗ Gonzalez, E. W. (1997). Resourcefulness, appraisals, and coping efforts of family caregivers. Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 18, 209-227. Greene, K., Kromar, M., Walters, L. H., Rubin, D. L., Hale, J., & Hale, L. (2000). Targeting adolescent risk-taking behaviors: The contributions of egocentrism and sensation-seeking. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 439-461. ∗ Hakim-Larson, J., Dunham, K., Vellet, S., Murdaca, L., & Levenbach, J. (1999). Parental affect and coping. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 31, 5-18. ∗ Hart, K. E., & Hittner, J. B. (1995). Optimism and pessimism: Associations to coping and angerreactivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 19, 827-839. ∗ Healy, C. M., & McKay, M. F. (2000). The effects of coping strategies and job satisfaction in a sample of Australian nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31, 681-688. Henson, R. K., Kogan, L. R., & Vacha-Haase, T. (2001). A reliability generalization study of the Teacher Efficacy Scale and related instruments. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61, 404-420. Henson, R. K., & Thompson, B. (2002). Characterizing measurement error in scores across studies: Some recommendations for conducting ‘‘reliability generalization’’ studies. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 35, 113-126. ∗ Hsu, Y., & Kuo, B. (2002). Evaluations of emotional reactions and coping behaviors as well as correlated factors for infertile couples receiving assisted reproductive technologies. Journal of Nursing Research, 10, 291-301. ∗ Hughes, M., McCollum, J., Sheftel, D., & Sanchez, G. (1994). How parents cope with the experience of neonatal intensive care. Children’s Health Care, 23, 1-14. ∗ Jelinek, J., & Morf, M. E. (1995). Accounting for variance shared by measures of personality and stress-related variables: A canonical correlation analysis. Psychological Reports, 76, 959-962. ∗ Johnson, C. N. E., & Hunter, M. (1997). Vicarious traumatization in counselors working in the New South Wales sexual assault service: An exploratory study. Work & Stress, 11, 319-328. ∗ Johnson, J. A. (1994). Appraisal, moods, and coping among individuals experiencing diagnostic exercise stress testing. Research in Nursing & Health, 17, 441-448. ∗ Johnson, S. B., & Carmichael, S. K. (2000). At-risk for diabetes: Coping with the news. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 7, 69-77. ∗ Kalichman, S. C. (1999). Psychological and social correlates of high-risk sexual behaviour among men and women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care, 11, 415-428. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 278 Educational and Psychological Measurement ∗ Kear-Colwell, J., & Sawle, G. A. (2001). Coping strategies and attachment in pedophiles: Implications for treatment. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 45, 171-182. ∗ Kemp, M. A., & Neimeyer, G. J. (1999). Interpersonal attachment: Experiencing, expressing, and coping with stress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 388-394. Kieffer, K. M., & Reese, R. J. (2002). A reliability generalization study of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62, 969-994. ∗ King, R. B., Carlson, C. E., Shade-Zeldow, Y., Bares, K. K., Roth, E. J., & Heinemann, A. W. (2001). Transition to home care after stroke: Depression, physical health, and adaptive processes in support persons. Research in Nursing & Health, 24, 307-323. ∗ Kuyken, W., & Brewin, C. R. (1994). Stress and coping in depressed women. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 18, 403-412. ∗ Kuyken, W., Peters, E., Power, M. J., & Lavender, T. (2003). Trainee clinical psychologists’ adaptation and professional functioning: A longitudinal study. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 10, 41-54. ∗ Landreville, P., Dube, M., Lalande, G., & Alain, M. (1994). Appraisal, coping, and depressive symptoms in older adults with reduced mobility. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 9, 269-286. ∗ Lapointe, V., & Marcotte, D. (2000). Gender-typed characteristics and coping strategies of depressed adolescents. European Review of Applied Psychology, 50, 451-460. Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 234-247. ∗ Mann, T., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Huang, K., Burgard, D., Wright, A., & Hanson, K. (1997). Are two interventions worse than one? Joint primary and secondary prevention of eating disorders in college females. Health Psychology, 16, 215-225. ∗ Manne, S. L., Sabbioni, M., Bovbjerg, D. H., Jacobsen, P. B., Taylor, K. L., & Redd, W. H. (1994). Coping with chemotherapy for breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 17, 41-55. Martin, P., Rott, C., Poon, L. W., Courtenay, B., & Lehr, U. (2001). A molecular view of coping behavior in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 13, 72-91. Massey, B. A. (1997). Victims or survivors: A three-part approach to working with older adults. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30, 193-202. McCown, D., & Davies, B. (1995). Patterns of grief in young children following the death of a sibling. Death Studies, 19, 41-53. ∗ Miller, A. C., Cate, I. M. P., & Johann-Murphy, M. (2001). When chronic disability meets acute stress: Psychological and functional changes. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 43, 213-216. ∗ Miller, A. C., Gordon, R. M., Daniele, R. J., & Diller, L. (1992). Stress, appraisal, and coping in mothers of disabled and nondisabled children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 17, 587-605. ∗ Mohr, D. C., Dick, L. P., Russo, D., Likosky, W., Pinn, J., Boudewyn, A. C., et al. (1999). The psychosocial impact of multiple sclerosis: Exploring the patient’s perspective. Health Psychology, 18, 376-382. ∗ Musil, C. M. (1998). Health, stress, coping, and social support in grandmother caregivers. Health Care for Women International, 19, 441-455. ∗ Mytko, J. J., Knight, S. J., Chastain, D., Mumby, P. B., Siston, A. K., & Williams, S. (1996). Coping strategies and psychological distress in cancer patients before autologous bone marrow transplant. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 3, 355-366. ∗ Narsavage, G. L., & Weaver, T. E. (1994). Physiologic status, coping, and hardiness as predictors of outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nursing Research, 43, 90-94. ∗ Neundorfer, M. M. (1991). Coping and health outcomes in spouse caregivers of persons with dementia. Nursing Research, 40, 260-265. Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Daniel, L. G. (2002). A framework for reporting and interpreting internal consistency reliability estimates. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 35, 89-103. ∗ Pakenham, K. I. (1998). Couple coping and adjustment to multiple sclerosis in care receiver-carer dyads. Family Relations, 47, 269-277. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 Rexrode et al. / Ways of Coping Scale Reliability ∗ 279 Pakenham, K. I. (1999). Adjustment to multiple sclerosis: Application of a stress and coping model. Health Psychology, 18, 383-392. Parker, J. D. A., & Endler, N. S. (1992). Coping with coping assessment: A critical review. European Journal of Personality, 6, 321-344. Parker, J. D. A., Endler, N. S., & Bagby, R. M. (1993). If it changes, it might be unstable: Examining the factor structure of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 5, 361-368. ∗ Patterson, G. T. (2000). Demographic factors as predictors of coping strategies among police officers. Psychological Reports, 87, 275-283. ∗ Patterson, G. T. (2002). Development of a law enforcement stress and coping questionnaire. Psychological Reports, 90, 789-799. ∗ Patterson, G. T. (2003). Examining the effects of coping and social support on work and life stress among police officers. Journal of Criminal Justice, 31, 215-226. Pedhazur, E. J., & Schmelkin, L. P. (1991). Measurement design and analysis: An integrated approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. ∗ Petersen, S., Heesacker, M., & Marsh, R. D. (2001). Medical decision making among cancer patients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48, 239-244. ∗ Pikler, V., & Winterwood, C. (2003). Racial and body image differences in coping for women diagnosed with breast cancer. Health Psychology, 22, 632-637. ∗ Reichman, S. R. F., Miller, A. C., Gordon, R. M., & Hendricks-Munoz, K. D. (2000). Stress appraisal and coping in mothers of NICU infants. Children’s Health Care, 29, 279-293. Reinhardt, B. (1996). Factors affecting coefficient alphas: A mini Monte Carlo study. In B. Thompson (Ed.), Advances in social science methodology (Vol. 4, pp. 3-20). Greenwich, CT: JAI. ∗ Rychtarik, R. G., & McGillicuddy, N. B. (1997). The Spouse Situation Inventory: A role-play measure of coping skills in women with alcoholic partners. Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 289-300. ∗ Scherer, R. F., Owen, C. L., Petrick, J. A., & Bodzinski, J. D. (1994). Situation-dependent work stress and sex effects on coping strategies: A multivariate analysis. Journal of Health and Human Resources Administration, 16, 266-285. ∗ Schuldberg, D., Karwacki, S. B., & Burns, G. L. (1996). Stress, coping, and social support in hypothetically psychosis-prone subjects. Psychological Reports, 78, 1267-1283. ∗ Schwarze, N. J., Oliver, J. M., & Handal, P. J. (2003). Binge eating as related to negative selfawareness, depression, and avoidance coping in undergraduates. Journal of College Student Development, 44, 644-652. Shelby, J. S. (1997). Rubble, disruption, and tears: Helping young survivors of natural disaster. In H. G. Kaduson, D. M. Cangeloni, & C. E. Schaefer (Eds.), The playing cure: Individual play therapy for specific problems (pp. 143-169). Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson. Shields, A. L., & Caruso, J. C. (2003). Reliability generalization of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 404-413. Shields, A. L., & Caruso, J. C. (2004). A reliability induction and reliability generalization study of the CAGE Questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64, 254-270. ∗ Shiffman, S., Hickcox, M., Paty, J. A., Gnys, M., Richards, T., & Kassel, J. D. (1997). Individual differences in the context of smoking lapse episodes. Addictive Behaviors, 22, 797-811. ∗ Sinha, B. K., Willson, L. R., & Watson, D. C. (2000). Stress and coping among students in India and Canada. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 32, 218-225. Smyth, K., & Yarandi, H. N. (1996). Factor analysis of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire for African American women. Nursing Research, 45, 25-29. ∗ Smyth, K. A., & Williams, P. D. (1991). Patterns of coping in Black working women. Behavioral Medicine, 17, 40-46. ∗ Stephens, M. A. P., Norris, V. K., Kinney, J. M., Ritchie, S. W., & Grotz, R. C. (1988). Stressful situations in care giving: Relations between caregiver coping and well-being. Psychology and Aging, 3, 208-209. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016 280 Educational and Psychological Measurement Stone, A. A., Kennedy-Moore, E., Newman, M. G., Greenberg, M., & Neale, J. M. (1992). Conceptual and methodological issues in current coping assessments. In B. N. Carpenter (Ed.), Personal coping: Theory, research, and application (pp. 15-29). Westport, CT: Praeger. ∗ Thornton, P. I. (1992). The relation of coping, appraisal, and burnout in mental health workers. Journal of Psychology, 126, 261-271. Vacha-Haase, T. (1998). Reliability generalization: Exploring variance in measurement error affecting score reliability across studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58, 6-20. Vache-Haase, T., Henson, R. K., & Caruso, J. C. (2002). Reliability generalization: Moving toward improved understanding and use of score reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62, 562-569. Vache-Haase, T., Ness, C., Nilsson, J., & Reetz, D. (1999). Practices regarding reporting of reliability coefficients: A review of three journals. Journal of Experimental Education, 67, 335-341. Vaillant, G. E. (1977). Adaptation to life. Boston: Little, Brown. ∗ Violanti, J. M. (1992). Coping strategies among police recruits in a high-stress training environment. Journal of Social Psychology, 132, 717-729. ∗ Vitaliano, P. P., Maiuro, R. D., Russo, J., & Mitchell, E. S. (1989). Medical student distress: A longitudinal study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 177, 70-76. ∗ Vitaliano, P. P., Russo, J., Carr, J. E., Maiuro, R. D., & Becker, J. (1985). The Ways of Coping Checklist: Revision and psychometric properties. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 20, 3-26. ∗ Wasley, D., & Lox, C. L. (1998). Self-esteem and coping responses of athletes with acute versus chronic injuries. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 86, 1402. ∗ Watson, D. C., & Sinha, B. K. (1999-2000). Stress, emotion, and coping strategies as predictors of personality disorder pathology. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 19, 279-294. ∗ Watson, D. C., Willson, L. R., & Sinha, B. K. (1998). Assessing the dimensional structure of coping: A cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Stress Management, 5, 77-81. Wilkinson, L., & the APA Task Force on Statistical Inference. (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist, 54, 594-604. ∗ Williamson, G. M., Walters, A. S., & Shaffer, D. R. (2002). Caregiver models of self and others, coping, and depression: Predictors of depression in children with chronic pain. Health Psychology, 21, 405-410. ∗ Wineman, N. M., Durand, E. J., & McCulloch, B. J. (1994). Examination of the factor structure of the Ways of Coping Scale with clinical populations. Nursing Research, 43, 268-273. ∗ Wonghongkul, T., Moore, S. M., Musil, C., Schneider, S., & Deimling, G. (2000). The influence of uncertainty in illness, stress appraisal, and hope on coping in survivors of breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 23, 422-429. Worden, J. W., Davies, B., & McCown, D. (1999). Comparing parent loss with sibling loss. Death Studies, 23, 1-15. Yin, P., & Fan, X. (2000). Assessing the reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory scores: Reliability generalization across studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60, 201-223. Downloaded from epm.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 5, 2016