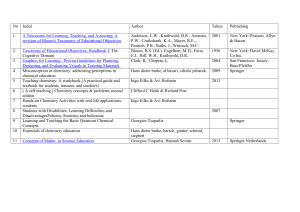

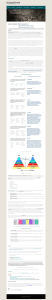

BACKGROUND PAPER Channeling Sustainable Finance: The Role of Taxonomies Eugene Wong DISCLAIMER This background paper was prepared for the report Asia-Pacific Climate Report 2024. It is made available here to communicate the results of the underlying research work with the least possible delay. The manuscript of this paper therefore has not been prepared in accordance with the procedures appropriate to formallyedited texts. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), its Board of Governors, or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this document and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or use of the term “country” in this document, is not intended to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this document do not imply any judgment on the part of the ADB concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. i Channeling Sustainable Finance: The Role of Taxonomies Eugene Wong Sustainable Finance Institute Asia Note: In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................. i LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES, BOX............................................................................................. ii ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................ iv I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. UNDERSTANDING TAXONOMIES................................................................................. 3 A. Defining Taxonomies ....................................................................................................... 3 B. Transition in Taxonomies ................................................................................................ 8 C. The Need for Taxonomies ..............................................................................................13 III. THE RISE OF SUSTAINABLE FINANCE TAXONOMIES IN DEVELOPING ASIA .........17 A. Comparison of Key Design Elements .............................................................................18 1. Taxonomy Objectives .................................................................................................18 2. Sector Coverage .........................................................................................................21 3. Climate Ambitions and Decarbonization Pathways Referenced for Taxonomy Assessments .....................................................................................................................23 4. B. Other Eligibility Criteria and Perspective on Technology .............................................25 Assessments ..................................................................................................................28 IV. TAXONOMY GOVERNANCE .........................................................................................32 V. ADDRESSING AND NAVIGATING THE INFLUENCE OF MULTIPLE TAXONOMIES ...32 A. One Activity, Multiple Taxonomies ..................................................................................32 B. Challenges in Developing and Implementing Taxonomies and Policy Approaches .........35 VI. CONCLUSION ...............................................................................................................41 APPENDIX: ILLUSTRATION OF THE GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE OF FIVE TAXONOMIES ANALYZED ...............................................................................................................................42 SELECTED REFERENCES ......................................................................................................44 i LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES, BOX Tables Table 1: Overview of Official Taxonomy Approaches ................................................................12 Table 2: Comparison of Environmental Objectives ....................................................................18 Table 3: Additional Taxonomy Characteristics ..........................................................................26 Table 4: ISIC 351 (Electric Power Generation, Transmission, and Distribution) Thresholds ......29 Figures Figure 1: Types of Taxonomies .................................................................................................. 4 Figure 2: Comparison of Multiple Classifications in Taxonomies ................................................ 7 Figure 3: Broad Users and Uses Identified ................................................................................16 Figure 4: Taxonomy Building Blocks .........................................................................................17 Figure 5: Coverage of Mongolia SDG Taxonomy ......................................................................20 Figure 6: Comparison of Taxonomy Sectoral Coverage ............................................................22 Figure 7: References to the Paris Agreement and Nationally Determined Contributions in Taxonomy Application ...............................................................................................................25 Figure 8: Comparison of Coal Phase-Out Criteria .....................................................................31 Figure A1: ASEAN Taxonomy and European Taxonomy Development Governance Structures .................................................................................................................................................42 Figure A2: Singapore Taxonomy and Malaysia Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy Governance Structures .............................................................................................................43 Figure A3: Indonesia Taxonomy Governance Structure ............................................................43 Box Box 1: Importance of Addressing Transition through Taxonomies—How the ASEAN Taxonomy Facilitates Inclusivity and Transition ..........................................................................................10 ii ABBREVIATIONS AMS ASEAN Member States ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations BNM Bank Negara Malaysia BSP Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas CCUS carbon capture, utilization, and storage CCPT Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy CPO coal phase-out CGT Common Ground Taxonomy DNSH do no significant harm IEA International Energy Agency ILO International Labour Organization ISIC International Standard Industrial Classification MAS Monetary Authority of Singapore NDCS Nationally Determined Contribution NACE Nomenclature generale des Activities economiques dans OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OJK Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (Financial Services Authority of Indonesia) RMT Remedial Measures to Transition SDGs Sustainable Development Goals SDS Sustainable Development Scenario SRI Sustainable and Responsible Investment TSC Technical Screening Criteria THI Indonesia Green Taxonomy iii ABSTRACT Taxonomies are increasingly gaining prominence as a powerful tool for classifying sustainable activities to guide action, especially in orienting capital. Understanding taxonomies and the role they play is important for all stakeholders, including policymakers, investors, and real economy participants. The paper examines the various official taxonomies in developing Asia, referencing them to other taxonomies where relevant, providing insights into the characteristics of existing taxonomies and the approaches that they take. It explains how taxonomies should be designed, navigated, used, and made interoperable as well as the challenges faced in taxonomy implementation. Taxonomies reflect national ambitions not just in environmental goals but also economic and social goals. Transition taxonomies can provide guidance for users with different starting points on using different pathways to reach the same agreed or pledged destination. This helps ensure that the orientation of capital and sustainability agenda goals are not misaligned. Taxonomies are a link between the financial sector and the real economy and need to be able to engender a “whole of economy” approach. As such, there is a need to incorporate the input of all relevant stakeholders. There are six key dimensions that are critical for a taxonomy’s success: (i) relevance; (ii) comprehensiveness; (iii) usability; (iv) robustness of ambition, or ability of an economy to meet its goals; (v) interoperability and equivalence; and (vi) future-proofed. Challenges exist in creating a taxonomy, as well as in implementing it, such as capacity, availability of data, and jurisdictional readiness. However, these should not stop the introduction of taxonomies as these challenges can be overcome with time and experience. Key words: sustainable, financing, climate, carbon-neutral, transition, transition finance, Sustainability Taxonomy, Transition Taxonomy, Green Taxonomy, Social Taxonomy, energy, transportation and storage, construction and real estate, agriculture, manufacturing, water, mining, carbon capture, information and communication, Paris Agreement iv I. INTRODUCTION With the impacts of climate change becoming more prominent by the day and the clock ticking, directing resources to address this challenge is critical. The finance sector plays a vital role in scaling up climate action. In a high-emissions scenario, developing Asia could face gross domestic product (GDP) losses of 24% due to climate change (ADB 2023a). Developing Asia will need $13.8 trillion in financing from 2023 to 2030 to sustain economic growth, reduce poverty, and respond to climate change. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) alone would need $3.1 trillion of infrastructure investments when adjusted for climate (ADB 2023b). At the same time, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are also progressing slower than needed. In orienting capital toward sustainability and sustainable economic activities, including climate action, the important question of where financing should be directed and what would qualify for financing and investment to meet the sustainability agenda has arisen. This has resulted in the return to a familiar solution adopted in biology to classify organisms, “taxonomies.” Taxonomies can be described in simple terms as comprehensive classification systems. There exists a plethora of official and private taxonomies that have been developed and issued. As of March 2024, more than 50 official taxonomies (national and regional) have been developed or are in development, with more in the form of proprietary taxonomies belonging to significant private sector entities. This potentially brings the number of taxonomies related to sustainability to over 200, ranging from proprietary and market taxonomies to widely referenced official taxonomies. Initially, sustainability and green definitions were less comprehensive and sophisticated, with the market providing broad principles and/or criteria, which were less complete and consistent. The consistency in the market’s approach improved considerably with the issuance of the Green Bond Principles by the International Capital Market Association in 2014, followed by the Social Bond Principles and Sustainability Bond Guidelines. However, this suite of principles provided broad guidance and as such, did not incorporate specific eligibility criteria. At the same time, the early forms of taxonomies began to emerge, such as Climate Bond Initiative’s Green Taxonomy (in 2013), which focused solely on climate change mitigation and was used for certification purposes; and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) China Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue 2015 Edition (PRC Catalogue 2015) in 2015, which applied to green bond issuances by financial institutions in the PRC. Additionally, the 1 Multilateral Development Bank–IDFC Common Principles for Climate Mitigation Finance Tracking Version 2 was published in 2015. In 2018, the European Commission established the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance to assist in developing the European Union (EU) Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities (EU Taxonomy), which came into force in 2020 (European Commission 2020). Taxonomies are normally not standalone solutions but are part of an ecosystem. For instance, the EU Taxonomy is one of the cornerstones of the EU Sustainable Finance Framework with Disclosures and Tools being the other two, while ASEAN’s Sustainable Finance Ecosystem has three pillars: taxonomy, transition finance frameworks, and disclosure. Taxonomies can provide a common language in identifying sustainable activities. In reflecting the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” adhered to in the Paris Agreement, a common but differentiated approach for taxonomies needs to be considered. This means that a taxonomy’s approach and assessment criteria may also need to be jurisdictionally contextualized to address national circumstances, including the different starting points, economic and social circumstances, and resources. Jurisdictional contextualization has resulted in the proliferation of taxonomies, making it essential to embed interoperability into the design of a taxonomy. Alternative approaches to sustainable finance taxonomies for providing guidance in identifying sustainable activities are also being used. These include the Japan Sector Roadmaps, which provide definitive directions for transition toward achieving carbon neutrality in 2050 for greenhouse gas (GHG)-intensive industries, developed by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan. The Japan Sector Roadmaps describe the technologies required to achieve carbon neutrality in challenging sectors by 2050. They are annexed to Japan’s Basic Guidelines on Transition Finance, which serve as a reference for companies looking to raise funding using transition bonds and/or loans. Given the important role of taxonomies, it is important to understand how they should be designed, how to navigate them, who should use them, how they should be used, and how they can be interoperable. This paper explores the landscape for a selection of official taxonomies in developing Asia,1 referencing them to other taxonomies where relevant. 1 This paper explores only official taxonomies. The Climate Bonds Initiative Taxonomy can be referenced as a proprietary or market taxonomy with international application. 2 II. UNDERSTANDING TAXONOMIES A. Defining Taxonomies A sustainable finance taxonomy is a comprehensive classification system that clearly defines which activities or projects are eligible for financing or investment based on criteria that meet the sustainability objectives of the taxonomy. Sustainable finance taxonomies can have a variety of configurations to meet specific needs. As such, it is difficult to rigidly and narrowly categorize taxonomies; instead, taxonomies are best defined by the key outcomes that they are intended to achieve and the approaches that they take. There are five features of taxonomies that have been issued or are currently under development: (i) Feature 1: Elements addressed. Sustainable finance taxonomies can cover different elements of sustainability as described in Figure 1. It should be noted that a taxonomy could include varying degrees of each of these elements and is not restricted to only one element. For instance, a Green taxonomy may have social and transition elements and a Transition taxonomy may emphasize “just” transition that gives weight to social aspects. As such, while a taxonomy can be classified based on its predominant element(s), it should not be “boxed in” as only containing that element. In addition, elements such as transition can be interpreted differently. For instance, the EU Taxonomy includes activities that are not considered as “green” or “sustainable”, but have no technologically or economically feasible low-carbon alternatives as transitional activities if they meet certain criteria. At the same time, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance (ASEAN Taxonomy) incorporates transition by applying a multitiered threshold approach to allow a transition pathway for economic activities. In practice, transition taxonomies are generally taken to mean taxonomies that explicitly support and facilitate transition, for instance, by having a specific transition category or multiple thresholds for their Technical Screening Criteria (TSC), such as Bank Negara Malaysia’s (BNM) Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy (CCPT) and the Principles-Based Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy (SRI Taxonomy) of Securities Commission Malaysia; the ASEAN Taxonomy; the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy (Singapore Taxonomy); Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1 (Thailand Taxonomy); Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable 3 Finance; and the Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Guidelines (Philippines Taxonomy). One way of describing taxonomy elements is provided in Figure 1. Figure 1: Types of Taxonomies Source: Author analysis. The PRC Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue 2021 Edition (PRC Catalogue) and Mongolia Green Taxonomy address climate and environmental aspects independently of social aspects. The EU Taxonomy has been described by some as being a “binary” green taxonomy in nature, as there is only a single threshold to determine whether an activity is aligned to the EU Taxonomy. On the other hand, in the ASEAN Taxonomy, there can be multiple thresholds for each economic activity that results in different taxonomy classifications, rather than only one classification that qualifies. It is important to point out that under the EU Taxonomy, to be “taxonomy-eligible”, an economic activity should substantially contribute to at least one of the six 4 environmental objectives of the EU Taxonomy. If it further meets the relevant TSC, satisfies the do no significant harm (DNSH) test, and complies with the minimum social safeguards requirement, then it is categorized as “taxonomy-aligned.” However, in this paper, “taxonomy-eligible” is defined as an economic activity that contributes to at least one taxonomy objective and satisfies the relevant criteria to be classified as Green, Amber, or their equivalents under the relevant taxonomy. This includes economic activities that are specifically listed or recognized as taxonomyeligible in a taxonomy, as discussed below. The EU and ASEAN taxonomies cover more than just climate objectives and include criteria that prevent harm to other environmental objectives as well as social aspects. (ii) Feature 2: Whitelist and performance outcome-based taxonomies. Some taxonomies are based on the performance outcomes of economic activities (ASEAN, the EU, the Republic of Korea), and are referred to as TSC-based or principles-based taxonomies (as relevant). Others prescribe what is eligible for investments (Bangladesh, the PRC, Kazakhstan, Mongolia) and are referred to as Whitelist taxonomies. Some taxonomies have Redlists, which specify excluded or ineligible activities. Performance outcomes-based taxonomies are generally technology-neutral (although some may reference technologies), while Whitelists do refer to specific technologies. (iii) Feature 3: Principles-based vs TSC-based. Performance outcomes-based taxonomies can either be principles-based or TSC-based. A principles-based taxonomy uses broad principles to classify economic activities. Examples of this 5 include the Philippines Taxonomy, both Malaysia taxonomies (CCPT and SRI), as well as the Foundation Framework of ASEAN Taxonomy. The Indonesia Taxonomy also incorporates a principles-based component. Principles-based frameworks are useful in helping users who do not have sufficient data to use a TSC frame in starting to classify their economic activities in broad, predefined terms. Assessments under taxonomies that use TSC apply a variety of quantitative and qualitative thresholds. Qualitative thresholds include compliance with processes or practices. Principlesbased taxonomies need to provide sufficient guidance in their use so that the results produced are consistent and credible. Principles-based taxonomies have the advantage of ease of use and rapid deployment, providing a means to start addressing taxonomy objectives faster. However, to meet specific targets, TSC will be needed. (iv) Feature 4: Economic activity vs financial instruments vs entity assessments. The application of taxonomies can be at the economic activity level, entity level, or financial instruments. For instance, the PRC Catalogue and the Mongolia (Green and SDG) taxonomies apply at the financial instruments level. The taxonomies of ASEAN; EU; Hong Kong, China; Indonesia; Malaysia (CCPT and SRI); the Philippines; Singapore; South Africa; and Thailand operate at the economic activity level. In addition, through activity aggregation methodologies, the EU, Singapore, and South Africa taxonomies allow the activity level assessments to be translated into entity-level assessments. (v) Feature 5: Single classification vs multiple classifications. Taxonomies can adopt an approach where an activity is either taxonomy-eligible or not; based on whether a TSC is met (e.g., EU and South Africa taxonomies); or if it is listed as eligible (the PRC and Mongolia). Alternatively, under a taxonomy, an activity can have more than one 6 classification based on the criteria that it meets (ASEAN, Singapore, and Thailand). The Traffic Lights approach is a common example of a multiclassification approach using the common categories of Green (meets ambition or criteria), Amber (transitioning), and Red (ineligible). Some taxonomies extend the concept by using a wider classification system; for example, BNM’s CCPT, which has five categories, while others may have fewer classifications, such as the Indonesia Taxonomy with only Green or Transition. Multiple classifications are helpful in providing an avenue to incorporate transition into taxonomies as seen in Figure 2. Figure 2: Comparison of Multiple Classifications in Taxonomies ASEAN= Association of Southeast Asian Nations, CCPT = Climate Change and Principles-Based, TSC = Technical Screening Criteria. Note: Classification of C1 to C5 in the CCPT is based on how an activity meets the criteria of the Guiding Principles. Sources: ASEAN Taxonomy Board. 2024. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 3; Bank Negara Malaysia. 2021. Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2024. Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Securities and Exchange Commission of the Philippines. 2024. Guidelines on the Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy. The growth in the number of taxonomies has been underpinned by the need and desire to cater to local specificities and serve specific objectives, including national priorities and agendas as reflected in the features of the selected taxonomies. As the purpose of a taxonomy includes 7 promoting capital flow toward specific themes, separate taxonomies can be developed for separate themes. Mongolia developed an SDG Finance Taxonomy following on from the Mongolia Green Taxonomy to specifically encourage investments into SDG-aligned activities and the creation of incentives to support those capital flows. The Mongolia SDG Taxonomy will eventually replace the Mongolia Green Taxonomy. The Securities Commission Malaysia created its SRI Taxonomy, following on from BNM’s CCPT, with additional emphasis on social aspects. Taxonomies can have either mandatory application, such as in the PRC or the EU, or be voluntary, such as in the Republic of Korea and ASEAN region. Financial institutions under BNM are required to report under the CCPT while the Central Bank of Mongolia and the Financial Regulatory Commission of Mongolia require financial institutions to report against the Mongolia Green Taxonomy. Taxonomies may opt to combine assessment frameworks to provide more useful assessment coverage. As such, taxonomies may contain a combination of principles-based, TSC-based, as well as Redlist and Whitelist assessment frameworks. B. Transition in Taxonomies It is unrealistic to decarbonize immediately due to hard-to-abate sectors, economic activities with no technologically and economically feasible low-carbon alternatives, infrastructure bottlenecks, and the risk of economic and social dislocations for economies that are not sufficiently resourced or prepared. As such, transition is necessary. A transition can be said to be the intersection of ambition and reality that, in the case of climate change action, can provide a realistic pathway for successful decarbonization. Countries, as well as companies, have different starting points and as such, it is important to provide different pathways to accommodate the different starting points toward a common end goal. There are activities that support the transition to a climate-neutral economy and those that enable activities to contribute substantially to environmental objectives—although they themselves do not substantially contribute to any environmental objectives. While there is presently no globally accepted standard for what constitutes a credible transition activity, incorporating a pathway for transition into taxonomies has become increasingly common to ensure that taxonomies better reflect the reality on the ground. The incorporation of transition into taxonomies often results in a 8 specific Amber classification, particularly in a Traffic Lights approach, as discussed previously, being applied. All taxonomies in the ASEAN region incorporate specific transition categories, making them Transition taxonomies (Box 1). Apart from recognizing transition categories specifically, allowing for a grace period to rectify any residual harm caused to a taxonomy objective in pursuit of another can support transition efforts. In the ASEAN Taxonomy, this is known as Remedial Measures to Transition (RMT). It should be emphasized that the ASEAN Taxonomy has found it important enough to include RMT as an essential criterion to enable activities that substantially contribute to one of its objectives, despite creating residual harm to another while ensuring that this unintended consequence can be remedied within an appropriate period. The Indonesia, Malaysia (CCPT and SRI), and Philippines taxonomies have also applied RMT in a similar manner to the ASEAN Taxonomy. Under the Thailand Taxonomy, any activity that does not meet its DNSH criteria, but meets the relevant TSC, may be considered eligible under either the Green or Amber category if the company provides a plan on how the deficiencies will be remedied within 3 years. The Singapore Taxonomy does not include allowance for RMT. Instead, in addition to having an Amber classification, the Singapore Taxonomy introduced the concept of “Amber Measures”, which are measures that do not meet the Amber activity thresholds but enable an activity to improve and align with “Green or “Amber” over a defined period. This is, however, limited to certain sectors. It is worthwhile noting that in the Singapore Taxonomy, DNSH criteria is included as a best practice and is not a requirement for an activity to be taxonomy-eligible. Unlike the ASEAN Taxonomy and ASEAN Member States (AMS) national taxonomies,2 the EU Taxonomy does not include a specific transition category. Instead, transition activities in hard-toabate sectors (e.g., electricity generation from fossil gaseous fuels) that do not hamper the development or deployment of low-carbon alternatives are included and classified as taxonomyeligible for a limited period under certain conditions. It should be noted that the EU had previously consulted on extending the taxonomy to include transition and immediate performance levels while Australia and Canada are developing transition taxonomies. 2 The AMS national taxonomies comprise the Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand taxonomies. 9 Box 1: Importance of Addressing Transition through Taxonomies—How the ASEAN Taxonomy Facilitates Inclusivity and Transition In charting the sustainability journey for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), it is crucial to consider the diverse circumstances of ASEAN Member States (AMS) and the challenge this poses in developing a regional taxonomy, which is to act as a common language for sustainable finance. ASEAN Member States are at varying stages of development and have different economic and social structures as well as resources, resulting in different starting points and the need for different pathways. At the time the ASEAN Taxonomy was being developed, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita per annum of AMS ranged from $1,286 to $59,785. In 2022, the range stood at $1,161–$82,795. In addition, ASEAN did not (and still does not) have a regional net zero target date, and there are variations to each AMS’ ambition. These challenges presented the need for a carefully considered approach in developing a sustainable finance classification framework that was inclusive yet aligned to meet Paris Agreement goal with a 1.5ºC ambition. A multitiered approached, both in the assessment frames as well as in the Technical Screening Criteria (TSC), was envisaged to address the needs of ASEAN to allow for different starting points and journeys but with the aim of reaching the same goal. The ASEAN Taxonomy explicitly incorporates transition in the following manner: • Incorporate two frames for assessment, the Foundation Framework (principles-based frame) and Plus Standard (TSC-based frame) to allow AMS with different states of readiness and data availability to immediately commence their transition journey. • Apply a traffic-lights system in both the Foundation Framework and Plus Standard to enable a multiclassification approach that provides a distinct Amber classification for transition activities. • Translate the Traffic Lights system into a multitiered approach for TSC that includes a Green Tier reflecting the taxonomy’s climate ambition, which is, wherever possible, benchmarked to the EU Taxonomy together with two tiers carrying Amber classifications that provide a progressive pathway to transition toward Green. All current AMS national taxonomies also include an Amber or Transition Tier. ● Include the concept of Remedial Measures to Transition to provide real economy participants with the opportunity to progress on a pathway to Green while being allowed a specified timeframe to incorporate remediation measures to mitigate the residual harm caused to an environmental objective in the pursuit of another. Source: Author’s analysis. 10 When incorporating transition into taxonomies, it is important to ensure that lock-ins and backloading are appropriately addressed. One concern is that having a transition category would result in carbon lock-ins as investments are directed toward improving high-emitting assets (OECD 2022a). Taxonomy safeguards such as the sunsetting of transition tiers after a period can play a meaningful role in avoiding lock-ins as it will propel users to improve the performance of their activities, over that period, toward the Green performance level. Through sunsetting, transition TSCs will expire after a certain period. In addition to sunsetting, scheduled threshold resets, where thresholds are reset to more stringent levels prior to the sunset date of a transition tier, also help ensure a move toward the Green performance level to discourage backloading. Apart from sunsetting and scheduled threshold resets, taxonomies that are developed as living documents will also see the criteria initially set change over time due to advancements in scientific, technological, and economic circumstances and become progressively more stringent to promote a pathway to Green. While sunsetting is an important safeguard for Transition taxonomies, the need for certainty amidst changing thresholds for investors and financiers needs to be addressed. An approach used is grandfathering, which is or is planned to be addressed in ASEAN, the EU, Indonesia, and South Africa. Grandfathering allows financial instruments that are taxonomy-eligible to retain their classification for a certain period, notwithstanding a change in the applicable TSC. Grandfathering can provide certainty to the market on the treatment of financial instruments and ease volatility concerns in using taxonomies (GTAG 2023). In the ASEAN Taxonomy, the mechanisms of sunsetting and grandfathering working in concert was designed to allow AMS to reflect their national priorities by extending or limiting sunset dates when applying the ASEAN Taxonomy, resulting in individual glidepaths. The Singapore Taxonomy, however, contains provisions that directly sunsets Amber activities, resulting in an existing classification becoming ineligible after sunsetting.3 Taxonomies may also encapsulate activities to avoid future emissions as part of the decarbonization objective and to support transition. For instance, given the region’s reliance and commitments on coal, the early retirement of coal-fired power plants or coal phase-out (CPO) is specifically catered for in several taxonomies in the ASEAN region. The frameworks used by, and approaches to transition, for a selection of taxonomies are provided in Table 1. 3 The guidance on Amber activities on page 20 of the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy provides that at the sunset date the activity must either follow the Green criteria or be taxonomy-ineligible. 11 Table 1: Overview of Official Taxonomy Approaches Taxonomy Assessment Framework Issuer Taxonomy Type ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance ASEAN Taxonomy Board Sustainability Taxonomy; Transition Taxonomy Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance* Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (Financial Services Authority of Indonesia) Sustainability Taxonomy; Transition Taxonomy Malaysia Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomyb Bank Negara Malaysia Transition Taxonomy Malaysia Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy Securities Commission Malaysia Sustainability Taxonomy; Transition Taxonomy Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Financial Sector Forum Sustainability Taxonomy; Transition Taxonomy Singapore-Asia Taxonomy Green Finance Industry Taskforce Sustainability Taxonomy; Transition Taxonomy Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1 Thailand Taxonomy Board Sustainability Taxonomy; Transition Taxonomy Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Hong Kong Monetary Authority Green Taxonomy PRC Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue 2021 Edition People’s Bank of China, National Green Taxonomy Development and Reform Council, China Securities Regulatory Commission Republic of Korea Green Taxonomy Ministry of Environment Sustainability Taxonomy Mongolia Green Taxonomy Financial Stability Commission of Mongolia Green Taxonomy Mongolia Sustainable Development Goals Taxonomy Bank of Mongolia, Deposit Insurance Corporation of Mongolia Sustainability Taxonomy Bangladesh Sustainable Finance Policy Bangladesh Bank Sustainability Taxonomy Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development Green Taxonomy European Union Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities European Commission Sustainability Taxonomy Sustainable Taxonomy of Mexico Ministry of Finance and Public Credit Sustainability Taxonomy South African Green Finance Taxonomy Taxonomy Working Group, as part of South Africa’s Sustainable Finance Initiative, chaired by National Treasury. Sustainability Taxonomy Principles-based Whitelist TSC-based Redlist SDG = Sustainable Development Goals, THI = Indonesia Green Taxonomy, TSC = Technical Screening Criteria. a The Indonesia Taxonomy refers to the predecessor Indonesia Green Taxonomy (THI) for matters not covered by the Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. The THI includes a Redlist. b Financial institutions are encouraged to refer to Bank Negara Malaysia’s Value-based Intermediation Financing and Investment Impact Assessment Framework sectoral guides for more detailed guidance to conduct Environmental, Social and Governance impact assessments in specific sectors Sources: Author analysis of ASEAN Taxonomy Board. 2024. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 3; Astana International Financial Center. 2021. Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy; 12 Bank Negara Malaysia. 2021. Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy; Bank of Thailand. 2023. Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1; Bangladesh Bank. 2020. Sustainable Finance Policy for Banks and Financial Institutions; European Commission. 2020. Taxonomy: Final Report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2022. Indonesia Green Taxonomy Edition 1.0; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2024. Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Government of the Republic of South Africa. 2022. South African Green Finance Taxonomy. 1st ed. Hong Kong Monetary Authority. 2024. Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Ministry of Environment of Korea. 2021. The Korean Green Taxonomy; Ministry of Finance and Public Credit Mexico. 2023. Sustainable Taxonomy of Mexico; Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2023. Singapore-Asia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Mongolian Sustainable Finance Association. Mongolia’s Sustainable Finance Journey & SDG Taxonomy; Mongolian Sustainable Finance Association. 2019. Mongolia Green Taxonomy. National Treasury; People’s Bank of China. 2021. Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue; Securities and Exchange Commission of the Philippines. 2024. Guidelines on the Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy; Securities Commission Malaysia. 2022. Principles-Based Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy. C. The Need for Taxonomies Taxonomies serve many purposes and there are various ways a taxonomy can be used by different users. The array of uses of a taxonomy would depend on its design and its place in the sustainable finance ecosystem. Taxonomies help with the following: (i) Providing consistent language and reference for different stakeholders. The primary purpose of taxonomies is to help direct capital toward sustainable activities that align with the relevant taxonomy’s objectives, such as environmental objectives. They provide common language for various stakeholders including investors, lenders, real economy participants, and governments. Different groups of users can use the same taxonomy to meet their individual needs. Investors can invest based on taxonomy-eligible activities and banks can use a taxonomy’s criteria in providing loans and setting conditions for them. A taxonomy can help in financial product creation and the creation of asset classes. In addition, policymakers can use a taxonomy to set out policies to promote activities that contribute to the relevant taxonomy objectives (see below). Taxonomies help providers of capital make more informed decisions in a simpler way. As a common language, taxonomies help lower transaction costs, such as due diligence cost for investors, and can increase confidence to invest or finance. Without a common language, investors and lenders would need to carry out additional due diligence to understand an investment or funding opportunity. This can be a disincentive to providing capital. Given the urgent need for investment into climate 13 change action, the absence of a credible taxonomy would result in reduced and delayed action. Importantly, taxonomies help link the financial sector and the real economy in relation to the sustainability agenda by guiding how the real economy can be financed in line with a sustainability or climate action agenda. For this reason, taxonomies must be designed with input from the real economy. Having a common language also reduces operational costs by identifying sustainable activities and harmonizing sustainability targets across various user groups. This is very important in helping drive a whole economy approach to sustainability as disparate action can lead to fragmentation. (ii) Helping businesses and project owners understand what they need to do to be eligible for sustainable financing. Real economy participants are often uncertain as to what they need to do to align to sustainability goals and to access financing. They can use a taxonomy to assess their sustainability performance to provide investors and financiers with better information to aid decision making processes. They can also be guided by a taxonomy in shaping their operational and technological transformations and investments. (iii) Supporting risk management and strategic decision-making. A taxonomy can be used to provide benchmarks in risk and opportunity analysis to understand risks including impairment, stranding, and greenwashing, as well as to identify and assess opportunities. The use of a taxonomy can also reduces greenwashing by providing credible benchmarks. (iv) Converting undertakings and pledges, such as the Paris Agreement or national pledges, into tangible action including by guiding government policy and market action. A taxonomy can help articulate the obligations of a country into clear targets. This articulation can help with government policy, including investment road maps, criteria for qualification for subsidies and incentives, and support for government climate action programs. In the case of taxonomies catering to a diverse group like the ASEAN Taxonomy, an overarching taxonomy can provide a frame for users with different starting points to take different pathways to reach the same agreed or pledged destination. Without such guidance, the orientation of capital and sustainability agenda goals may be misaligned. 14 The development of taxonomies accounts for the needs and capabilities of the taxonomy jurisdiction. Taxonomies of developed countries like the EU and the Republic of Korea were designed to support the EU Green Deal and the Korean Green New Deal, respectively. The PRC Catalogue is aimed at, inter alia, building a green financial system, supporting structural transformation, and facilitating sustainable economic growth in line with its net zero target. In all three cases, the taxonomy design aligned to the jurisdictional starting points, goals, and capabilities. In ASEAN, the economic and social conditions and resource availability necessitated transition to be a key feature. Figure 3 provides an overview of the key users and uses identified across official taxonomies. It should be noted that the more comprehensive, credible, and relevant a taxonomy is, the more uses may unfold. For instance, prudential regulators may use taxonomies for risk and capital adequacy assessments, banks may price loans based on taxonomies, trade agreements and rules may refer to taxonomies, and taxonomies may be referenced for imports. As an illustration of user needs impacting taxonomy design, in Indonesia and the Philippines, a simplified principles-based framework has been introduced to accommodate micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) respectively, which make up approximately 99% of business establishments in those countries.4 Usability is an important consideration for developing countries owing to the lack of data and/or capability to carry out more detailed TSC-based assessments. Additionally, as SMEs and MSMEs make up approximately 97% of the ASEAN economy, this group must be part of the efforts for the region to reach its decarbonization goals. In this instance, in ensuring usability to cater to its diverse user base, both in terms of countries and businesses, the ASEAN Taxonomy provides a choice of two alternative assessment frames—a principles-based frame, i.e., the principles-based (Foundation Framework) and a TSC-based frame, i.e., the Plus Standard—for assessments to ensure that every member state and business has a frame that can be used immediately (principles-based) with the eventual goal of adopting the TSC-based frame. 4 In Indonesia, a principles-based approach as well as simplified DNSH and Social Aspects criteria for MSMEs are provided. In the Philippines, a simplified approach for MSMEs in assessing activities is provided. 15 Figure 3: Broad Users and Uses Identified Sources: Author analysis of ASEAN Taxonomy Board. 2024. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 3; Astana International Financial Center. 2021. Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy; Bank Negara Malaysia. 2021. Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy; Bank of Thailand. 2023. Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1; Bangladesh Bank. 2020. Sustainable Finance Policy for Banks and Financial Institutions; European Commission. 2020. Taxonomy: Final Report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2022. Indonesia Green Taxonomy Edition 1.0; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2024. Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Hong Kong Monetary Authority. 2024. Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Ministry of Environment of Korea. 2021. The Korean Green Taxonomy; Ministry of Finance and Public Credit Mexico. 2023. Sustainable Taxonomy of Mexico; Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2023. Singapore-Asia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Mongolian Sustainable Finance Association. Mongolia’s Sustainable Finance Journey & SDG Taxonomy; National Treasury; People’s Bank of China. 2021. China Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue; Republic of South Africa. 2022. South African Green Finance Taxonomy 1st Edition. Securities and Exchange Commission of the Philippines. 2024. Guidelines on the Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy; Securities Commission Malaysia. 2022. Principles-Based Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy. Developing countries may also need to address internal social vulnerabilities. Taking the Mexico Sustainable Taxonomy as an example, social objectives were introduced with the intention of addressing social gaps by defining activities that would promote social improvement within the country. Social aspects can also be incorporated as additional criteria in taxonomies. The EU Taxonomy addresses this through a Minimum Safeguards test. In the ASEAN Taxonomy, social aspects were introduced as a safeguard as part of the “essential criteria” that needs to be fulfilled together without causing harm to other environmental objectives, in addition to contributing significantly to an environmental objective. This reflects the ASEAN Taxonomy’s nature as a Sustainability taxonomy rather than a Green taxonomy. This approach can also be seen in the Republic of Korea, Malaysia (CCPT and SRI), Indonesia, and the Philippines. 16 III. THE RISE OF SUSTAINABLE FINANCE TAXONOMIES IN DEVELOPING ASIA Developing Asia has seen a mushrooming of taxonomies. The growth in taxonomies has been underpinned by the need and desire to cater to jurisdictional specificities and serve specific objectives, including national priorities, strategies, and agendas. An increase in the number of taxonomies also increases the risk of fragmentation. However, there are several design building blocks for taxonomies, and the way those building blocks are used will determine a taxonomy’s eventual design and interoperability. The more commonality there is in the building blocks used to construct taxonomies, the more interoperable the taxonomies will be. The taxonomy building blocks is illustrated in Figure 4. Figure 4: Taxonomy Building Blocks Source: Author. The following review of selected taxonomies compares how key building blocks have been used in their development. It is important to note that most taxonomies are developed in stages. Certain elements may not be included in the current iteration of a taxonomy but may be planned for inclusion in future versions. In the analysis, where information has been made publicly available at the time of writing regarding the future inclusion of a taxonomy element (e.g., environmental objectives, sector coverage), that element will be considered as included. 17 A. Comparison of Key Design Elements 1. Taxonomy Objectives Every taxonomy will have its own objectives that support its national priorities and external commitments, such as the Paris Agreement. Globally, taxonomy objectives may be described differently but refer to the same thing. The taxonomies reviewed in Table 2 all cover only environmental objectives as taxonomy objectives at present, except for the Malaysia SRI Taxonomy that also includes social objectives, the Mongolia SDG Taxonomy that encompasses the SDGs, and the Mexico Taxonomy that covers social objectives. Table 2: Comparison of Environmental Objectives Environmental Objectives Resource Resilience and Transition to Circular Economy Pollution Prevention and Control Sustainable Protection of Water and Marine Resources ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance * * Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance * * * * Malaysia Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy† * * Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy * * Taxonomy Malaysia Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy Protection of Climate Climate Healthy Change Change Ecosystems and Mitigation Adaptation Biodiversity * * Singapore-Asia Taxonomy * Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1 PRC Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue 2021 Edition Taxonomy objectives align with environmental objectives 18 Environmental Objectives Taxonomy Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Protection of Climate Climate Healthy Change Change Ecosystems and Mitigation Adaptation Biodiversity Resource Resilience and Transition to Circular Economy Pollution Prevention and Control Sustainable Protection of Water and Marine Resources ** Republic of Korea Green Taxonomy Mongolia Green Taxonomy Taxonomy objectives align with environmental objectives Mongolia SDG Taxonomy† Taxonomy objectives align with environmental objectives Bangladesh Sustainable Finance Policy Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy Taxonomy objectives align with environmental objectives European Union Taxonomy Sustainable Taxonomy of Mexico† South African Green Finance Taxonomy * means environmental objective is not discretely identified, but has been subsumed under another relevant environmental objective. ** means environmental objective is being considered for future inclusion. Currently, climate change mitigation is the central environmental objective of the Hong Kong, China Taxonomy. † means the taxonomy also covers objectives other than environmental objectives. ASEAN=Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Source: Author analysis of ASEAN Taxonomy Board. 2024. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 3; Astana International Financial Center. 2021. Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy; Bank Negara Malaysia. 2021. Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy; Bank of Thailand. 2023. Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1; Bangladesh Bank. 2020. Sustainable Finance Policy for Banks and Financial Institutions; European Commission. 2020. Taxonomy: Final Report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2022. Indonesia Green Taxonomy Edition 1.0; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2024. Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Hong Kong Monetary Authority. 2024. Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Mongolian Sustainable Finance Association. Mongolia’s Sustainable Finance Journey & SDG Taxonomy; Ministry of Environment of Korea. 2021. The Korean Green Taxonomy; Ministry of Finance and Public Credit Mexico. 2023. Sustainable Taxonomy of Mexico; Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2023. Singapore-Asia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Mongolian Sustainable Finance Association. 2019. Mongolia Green Taxonomy. National Treasury, Republic of South Africa. 2022. South African Green Finance Taxonomy 1st Edition; People’s Bank of China. 2021. Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue; Securities and Exchange Commission of the Philippines. 2024. Guidelines on the Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy; Securities Commission Malaysia. 2022. Principles-Based Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy; 19 Almost all the 13 taxonomies reviewed have explicitly included climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation as taxonomy objectives. This is followed by resource resilience and transition to a circular economy, and protection of healthy ecosystems and biodiversity (11). Less than half (7) have explicitly included pollution prevention and control, and sustainable protection of water and marine resources (6). Nevertheless, the TSC-based and principles-based taxonomies that have not distinctly identified these two environmental objectives have subsumed them under one of the other four environmental objectives. Similarly, while some other environmental objectives are not explicitly included in the reviewed taxonomies, they have been subsumed under one of the environmental objectives as indicated above. Although the Whitelist Asian taxonomies reviewed did not distinctly specify their objectives according to these definitions, they still encapsulate these objectives. For instance, from the mapping exercises conducted through the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT),5 it can be seen that the PRC Catalogue’s objectives can be mapped to all of the EU Taxonomy’s environmental objectives. The Malaysia SRI Taxonomy also incorporates the following social objectives: (i) enhanced conduct toward workers, (ii) enhanced conduct toward consumers and end-users, and (iii) enhanced conduct toward affected communities and wider society. The Mongolia SDG Taxonomy on the other hand, aims to meet SDG goals instead. This taxonomy extends the social objectives of taxonomies as seen in Figure 5. Figure 5: Coverage of Mongolia SDG Taxonomy GHG=greenhouse gas, SDG= Sustainable Development Goals. Source: Mongolia Sustainable Finance Association. Presentation on Mongolia’s Sustainable Finance Journey & SDG Taxonomy. 5 The CGT maps the PRC Catalogue and EU Taxonomy design elements, criteria, and thresholds to establish interoperability between the two taxonomies. 20 2. Sector Coverage The sector coverage for taxonomies will vary based on national goals and the purpose and objectives of the taxonomy. For instance, if a purpose of the taxonomy is to support decarbonization, then the sectors covered would be those that contribute most to GHG emissions. The sectors covered by the ASEAN Taxonomy contribute to over 85% of the region’s emissions. The following economic sectors are covered by the taxonomies reviewed: (i) Electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply (energy) (ii) Transportation and storage (iii) Construction and real estate (iv) Agriculture, forestry, and fishing (v) Manufacturing (vi) Water supply, sewerage, and waste management (vii) Mining (viii) Carbon capture, storage, and utilization (ix) Information and communication (x) Professional, scientific, and technical A number of taxonomies, such as in ASEAN, the EU, the Republic of Korea, Mongolia (both), and South Africa recognize the role of enabling sectors that have activities that improve or enable the performance of other sectors but themselves do not contribute substantially to an environmental objective and themselves do not risk harm to environmental objectives. However, such enabling activities may be classified differently in different taxonomies. The common enabling sectors recognized in the reviewed taxonomies are carbon capture, storage, and utilization; information and communication; and professional, scientific, and technical. This has also been the approach in various AMS national taxonomies (e.g., Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand). Figure 6 shows the sector coverage of the taxonomies reviewed. 21 Figure 6: Comparison of Taxonomy Sectoral Coverage Taxonomy Sectors ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Malaysia Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy Sector-agnostic Malaysia Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy Sector-agnostic Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Singapore-Asia Taxonomy Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1 Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance * * China Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue 2015 Edition Republic of Korea Green Taxonomy Mongolia Sustainable Development Goals Taxonomy Mongolia Green Taxonomy Bangladesh Sustainable Finance Policy Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy European Union Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities Sustainable Taxonomy of Mexico South African Green Finance Taxonomy ASEAN= Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Note: The Hong Kong, China sector is being considered for inclusion in future iterations of the taxonomy. Source: Author’s analysis 22 Fifteen taxonomies have prioritized the inclusion of the energy sector as well as water supply, sewerage, and waste management as focus sectors. Energy is a common priority, as this sector contributes to the bulk of emissions globally. Other focus sectors that are commonly covered include agriculture, forestry, and fishing; transportation and storage; construction and real estate; and manufacturing. At this point, however, the EU Taxonomy does not cover fisheries. In addition, criteria for sectors may be developed gradually, with the priority sectors coming first. This can be seen in the ASEAN Taxonomy (energy, followed by transportation and storage, and construction and real estate); and Thailand Taxonomy (energy and transportation). The sectors covered, and the priority in the deployment of the assessment criteria, reflect differing national or regional priorities. A taxonomy may also focus on sectors that are uniquely important to the jurisdiction’s economy. For example, the mining sector is only included in the Indonesia and South Africa taxonomies. While South Africa has yet to develop its criteria, Indonesia has included criteria for the sector to support the extraction of critical minerals for the manufacturing and development of clean energy technology (e.g., electric vehicles). Purely principles-based taxonomies generally do not specify focus sectors and are therefore sector-agnostic to allow flexible assessment. The Philippines taxonomy, while principles-based, does focus its application on sectors covered by the Philippines nationally determined contributions (NDCs). A further point to note on sector coverage is how economic activities under each sector are identified. This is a cornerstone for interoperability. Taxonomies of ASEAN, AMS national, the Republic of Korea, and South Africa all use a classification system consistent with the International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC), while the EU Taxonomy uses Nomenclature generale des Activities economiques dans, which is easily reconcilable to ISIC. While there may be some differences in the activity classifications in taxonomies, they are substantially consistent. 3. Climate Ambitions and Decarbonization Pathways Referenced for Taxonomy Assessments Climate ambition and decarbonization pathways are important references and bases for TSCbased taxonomies in setting TSC but this aspect of taxonomy construction is often not given much 23 attention (OECD 2020). Various pathways reflecting different long-term ambitions and targets relevant to each jurisdiction may be available. The Paris Agreement and NDCs are two of the most common references for climate ambition and decarbonization pathways, respectively. Notwithstanding design interoperability, when taxonomies reference different pathways to reflect jurisdictional specificity, the approach to achieving the Paris Agreement ambition will vary. Across the Developing Asia taxonomies reviewed, the climate ambition is commonly referenced to a science-based 1.5°C pathway, aligning with the preference of the Paris Agreement and the ambition of the EU Taxonomy. They also refer to the relevant NDCs, particularly for transition activities. The Amber Tiers of the ASEAN Taxonomy’s Energy TSC are set in reference to the International Energy Agency (IEA)’s Southeast Asia Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) pathway, augmented for additional rigor. The AMS national taxonomies may also choose to refer to the SDS pathway in setting their own thresholds for consistency with the ASEAN Taxonomy or use an alternative pathway, such as NDCs, and map the resulting thresholds against those of the ASEAN Taxonomy. Such an approach will result in equivalences being established, resulting in consistency and comparability. Equivalence goes beyond interoperability and enables a classification in one taxonomy to be mapped to the classification in a corresponding taxonomy. In the ASEAN region, for instance, the thresholds in AMS national taxonomies can be mapped to a threshold in the ASEAN Taxonomy, enabling conversion of any AMS national taxonomy threshold to one in the ASEAN Taxonomy. In this way, the ASEAN Taxonomy is the common reference for all AMS national taxonomies, becoming the universal reference point. Principles-based taxonomies are intended to encourage activities that contribute to meeting the NDCs; national policies; and/or the Paris Agreement (e.g., Malaysia CCPT and SRI, and Philippines taxonomies) from a directional perspective. Similarly, Whitelist taxonomies may include or exclude activities in line with decarbonization pathways (e.g., the PRC Catalogue excluding coal in alignment with a 1.5°C pathway). Activities that contribute to meeting national policies, NDCs, and/or Paris Agreement may also be identified in Whitelist taxonomies (e.g., Mongolia Green Taxonomy, including activities that support national policies in meeting the Paris Agreement). The application of references to decarbonization pathways in taxonomies is shown in Figure 7. 24 Figure 7: References to the Paris Agreement and Nationally Determined Contributions in Taxonomy Application ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations, NDCs = nationally determined contributions. Source: Author’s analysis. 4. Other Eligibility Criteria and Perspective on Technology A third building block of taxonomies is other eligibility criteria applied, namely, DNSH, social aspects, remedial measures to transition, and technology neutrality (Table 3). The first of these criteria, DNSH, refers to not causing harm to another taxonomy objective while substantially contributing to an objective. All the TSC-based taxonomies reviewed apply the DNSH criterion, while the Whitelist Bangladesh Taxonomy also adopts this concept. DNSH is important in ensuring that an economic activity that substantially contributes to a taxonomy objective does not create negative effects elsewhere. 25 Table 3: Additional Taxonomy Characteristics Technology Neutrality Social Aspects ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Yes Yes Yes Yes Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Partial Yes Yes Yes Malaysia Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy Yes No Yes Yes Malaysia Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy Yes Yes Yes Yes Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Yes Yes Yes Yes Singapore-Asia Taxonomy Yes Yes Yes# No Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1 Yes Yes Yes Yes † Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Yes ** Yes No China Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue 2015 No Edition *** No No Republic of Korea Green Taxonomy Partial Yes Yes No Mongolia Green Taxonomy No Yes No No Mongolia Sustainable Development Goals Taxonomy No * No No Bangladesh Sustainable Finance Policy No Yes Yes No Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy No No No No European Union Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities Yes Yes Yes No Taxonomy DNSH RMT ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations, DNSH = do no significant harm. Goals, RMT = is remedial measures to transition. * means addresses Sustainable Development Goals. ** means feature being considered for future inclusion. *** means requirement to consider safety, environmental, and quality regulations. † means taxonomy allows for activities, projects, or companies that do not comply with the DNSH criteria but satisfy the relevant technical screening criteria; metrics will be considered compliant for the corresponding Green or Amber category if the operating company submits an additional plan indicating how it will correct the deficiencies within 3 years after the assessment. # Currently best practice disclosure but may be incorporated as a component of eligibility criteria in the future. Sources: Author’s analysis of ASEAN Taxonomy Board. 2024. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 3; Astana International Financial Center. 2021. Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy; Bank Negara Malaysia. 2021. Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy; Bank of Thailand. 2023. Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1; Bangladesh Bank. 2020. Sustainable Finance Policy for Banks and Financial Institutions; European Commission. 2020. Taxonomy: Final Report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2022. Indonesia Green Taxonomy Edition 1.0; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2024. Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Hong Kong Monetary Authority. 2024. Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Mongolian Sustainable Finance Association. Mongolia’s Sustainable Finance Journey & SDG Taxonomy; Ministry of Environment of Korea. 2021. The Korean Green Taxonomy; Ministry of Finance and Public Credit Mexico. 2023. Sustainable Taxonomy of Mexico; Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2023. Singapore-Asia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Mongolian Sustainable Finance Association. 2019. Mongolia Green Taxonomy. National Treasury, Republic of South Africa. 2022. South African Green Finance Taxonomy 1st Edition; People’s Bank of China. 2021. Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue; Securities and Exchange Commission of the Philippines. 2024. Guidelines on the Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy; Securities Commission Malaysia. 2022. Principles-Based Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy. 26 The purpose of sustainability and climate taxonomies is ultimately to benefit the planet and its inhabitants. As such, it is only natural that social aspects are considered. All the TSC-based taxonomies reviewed consider social aspects. Variations may exist in the extent the social aspects are considered, but they are considered as an essential element that needs to be met to be taxonomy-eligible. The Singapore Taxonomy and the EU Taxonomy consider the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises (OECD MNE Guidelines) and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), with specific reference to the International Labour Organization (ILO) Core Labour Conventions. The EU Taxonomy additionally considers the International Bill of Human Rights. The ASEAN Taxonomy takes into account the following: (i) promotion and protection of human rights, with reference to the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD) and the Phnom Penh Statement on the Adoption of the AHRD; (ii) prevention of forced labor and protection of children’s rights, in line with the ASEAN Declaration on the Protection of the Rights of Migrant Workers and the ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of Rights of Migrant Workers; and (iii) impact of taxonomy on people living close to investments, in line with the ASEAN Declaration on Strengthening Social Protection. Among the Whitelist taxonomies, the Mongolian Taxonomies (Green and SDG) and the Bangladesh Sustainable Finance Policy also address social aspects, while the PRC Catalogue requires safety, environmental, and quality regulations to be complied with. On the other hand, the Malaysia SRI Taxonomy incorporates social aspects as a taxonomy objective. The third eligibility criterion is remedial measures to transition to facilitate transition. In some situations, an activity that contributes substantially to a taxonomy objective is causing or may cause significant harm at the same time to an environmental objective. To still benefit from the activity’s ability to make a substantial contribution, a realistic and comprehensive plan must be put in place to mitigate the harm to a level at which it is no longer significant. This plan must demonstrate that there will no longer be any significant harm occurring within a period after assessment of the activity. In the ASEAN, Indonesia, and Philippines taxonomies, this period is 5 years. Complying with this criterion allows an activity with such characteristics to be classified as 27 a Transition activity. The Philippines Taxonomy also allows remediation to extend up to 10 years with the support of an independent verification. On the other hand, the Thailand Taxonomy allows activities that do not meet DNSH to be taxonomy-eligible if the user provides a plan on how the harm will be remediated within 3 years. The inclusion of this facilitative criterion demonstrates the need for slightly different approaches for jurisdictions to account for different staring points and capabilities. The Singapore Taxonomy however, does not include provisions for RMT. The DNSH criteria is included there as a best practice and not as a requirement for an activity to be taxonomyeligible. Taxonomies can also be distinguished by whether the type of technology that is used is considered as part of the taxonomy criteria. Technology type is a cornerstone of the Japan Sector Roadmap. It can be noted from this review that TSC-based taxonomies are mostly technologically neutral while Whitelist taxonomies are generally technology-specific. B. Assessments Of the taxonomies reviewed, all the taxonomies that are principles-based or incorporate principles-based components are from ASEAN—Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Since principles-based taxonomies, like any other framework premised on principles, can produce inconsistent outcomes, the taxonomies reviewed have mitigated this by providing decision trees, detailed guiding questions, and use cases. The EU Taxonomy has been used as the ambition benchmark for most TSC-based taxonomies reviewed, including that of ASEAN; Hong Kong, China; Indonesia; the Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Thailand. For example, the upper limit for the threshold for ISIC 351 - Electricity Generation, Transmission and Distribution, Storage, is 100 grams carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt-hour across the TSC-based AMS national taxonomies and the ASEAN Taxonomy. The ASEAN Taxonomy’s Amber Tier 2 and 3 provide alternative pathways to meeting the IEA SDS goal for users that are not capable of meeting the Tier 1 climate ambition immediately yet wish to begin their sustainable journey. As the ASEAN Taxonomy Board also includes ASEAN national taxonomy developers, careful consultation and considerable effort has been put in to ensure that the thresholds for the Amber Tier in the AMS national taxonomies and the ASEAN Taxonomy’s Amber Tiers are compatible. However, while the EU Taxonomy does not have a Transition tier, it 28 does contain transition elements, such as a conditionally higher threshold limit for energy generation. For further details, please refer to Table 4. Table 4: ISIC 351 (Electric Power Generation, Transmission, and Distribution) Thresholds Indonesia* Singapore Thailand Hong Kong, China European Union Taxonomy Green <100 g <100 g (lifecycle CO2e/kWh CO2e/kWh emissions) Green Tier Equivalent to Green in the ASEAN Taxonomy ≤100 g CO2e/kWh Equivalent to Green in the ASEAN Taxonomy 100 g CO2e/kWh Equivalent to Green in the ASEAN Taxonomy <100 g CO2e/kWh Equivalent to Green in the ASEAN Taxonomy <100 g CO2e/kWh Equivalent to Green in the ASEAN Taxonomy Category ASEAN or <270 g CO2e/kWh*** Equivalent to Amber Tier 2 in the ASEAN Taxonomy Transition ≥100 and <510 g 220 g (lifecycle <425 g CO2e/kWh CO2e/kWh** emissions) CO2e/kWh Equivalent to Equivalent to Amber Tier Amber Tier 3 in Amber Tier 2 in 2 the ASEAN the ASEAN Taxonomy Taxonomy 381 g N/A CO2e/kWh Equivalent to Amber Tier 2 in the ASEAN Taxonomy N/A ≥425 and <510 g CO2e/kWh Amber Tier 3 ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations, CO2e = carbon dioxide equivalent, g = gram, kWh = kilowatt-hour, N/A = not applicable. * means the Indonesia Taxonomy allows emissions measurement using direct emissions until 2028 for users that are not able to measure lifecycle emissions. ** means the Singapore Taxonomy refers to direct emissions for its Amber threshold. *** means only applicable when the facility’s construction permit is granted before 2031. Sources: ASEAN Taxonomy Board. 2024. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 3; Bank of Thailand. 2023. Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1; European Commission. 2020. Taxonomy: Final Report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2024. Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Hong Kong Monetary Authority. 2024. Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2023. Singapore-Asia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. In the assessment of coal phase-out, it is estimated that coal power plants produced a fifth of all global greenhouse gas emissions in 2021(IEA 2021). Reducing the usage of coal would therefore have a significant impact on curbing the rise of global temperatures. Southeast Asia is highly reliant on coal for its energy generation needs. In 2020, it was estimated that coal supplied 7.5 exajoules (EJ) of energy to the region, approximately a quarter of the total 29 demand of 29.1 EJ (IEA 2022). Therefore, the reduction of coal usage is an imperative and a mechanism is needed to facilitate this. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) published Managed Phaseouts of Highemitting Assets in June 2022, while the CBI, Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), and Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) jointly published the Guidelines for Financing a Credible Coal Transition (GFANZ 2023; CBI, Climate Policy Initiative and RMI 2022). These were among the first guidelines outlining recommendations on how a phase-out of coal could be managed successfully. Significant programs have also been announced to encourage CPO, such as the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP)6 and the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM),7 signaling interest in channeling finance to such projects. To encourage early action to reduce the region’s reliance on coal as a major energy source, in a global first, the ASEAN Taxonomy Version 2 that was issued in March 2023 included CPO criteria as part of its Energy sector TSC. Stakeholder feedback affirmed that this was a useful first step in driving the phase-out of coal in the region. Following this, the Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance, which was issued in February 2024, also included criteria for CPO that are closely aligned with that of the ASEAN Taxonomy. The Singapore Taxonomy also included guidance on CPO but categorized and assessed it separately from other activities. The Singapore approach assesses CPO at the facility, entity and system levels, differing from the usual activitylevel assessment. The CPO criteria under the different frameworks above have the following similarities: (i) Reference to the IEA Net Zero Emissions pathway; (ii) the need for a duration cap on the operation of coal power plants; (iii) a set phase-out date; and (iv) demonstrable emissions savings. A comparison of requirements for eligible CPO under different frameworks is provided in Figure 8. 6 7 United Nations Development Programme. Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). ADB launched the ETM program in partnership with developing member countries (DMCs) that will leverage a market-based approach to accelerate the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy. 30 Figure 8: Comparison of Coal Phase-Out Criteria CBI = Climate Bonds Initiative, CPI = Climate Policy Initiative, IEA NZE= International Energy Agency Net Zero Emissions Pathway, FI = Financial Institution, gCO2 = grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per gram, kWh = kilowatthour, RMI= Rocky Mountain Institute, OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Sources: Author analysis of ASEAN Taxonomy Board. 2024. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 2; CBI, CPI and RMI. 2022. Working Paper: Guidelines for Financing a Credible Coal Transition—A Framework for Assessing the Climate and Social Outcomes of Coal Transition Mechanisms; Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 2024. Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance; Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero. 2023. Financing the Managed Phaseout of Coal-Fired Power Plants in Asia Pacific. Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2023. Singapore-Asia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. 31 IV. TAXONOMY GOVERNANCE A taxonomy may also be shaped by the institutions governing it. In most cases, financial regulators are involved in the development of sustainable finance taxonomies as those taxonomies may be intended to form part of a larger policy effort to channel sustainable finance. The environmental ministry of a country may also lead the development of a taxonomy to promote green activities (e.g., Korean Green Taxonomy). A mix of stakeholders may be engaged throughout the development, implementation, and review of a taxonomy. A summary of the governance structures of a few of the taxonomies reviewed8 can be found in Appendix A. As taxonomies are living documents, it can be observed that taxonomy maintenance is critical, and having a body mandated to review and adjust a taxonomy as needed over time to play its role is important. It is imperative that a taxonomy be periodically reviewed to ensure it remains relevant. Additionally, a variety of stakeholders may be engaged throughout the development of a taxonomy, whether as part of a taxonomy’s governance structure (e.g., Singapore Taxonomy) or through structured external engagements (e.g., ASEAN Taxonomy). Because there will always be divergent views among stakeholders, a robust governance mechanism will help ensure that decisions on a taxonomy are made effectively. V. ADDRESSING AND NAVIGATING THE INFLUENCE OF MULTIPLE TAXONOMIES A. One Activity, Multiple Taxonomies As discussed earlier, there has been a plethora of taxonomies—both official and proprietary market—being issued or under development. Global capital flows can result in the extraterritorial application of a taxonomy. Take for example a situation where a German bank’s Singapore subsidiary provides a loan for a project in Indonesia. Equity is provided by an Indonesian investor and a Japanese private equity firm. Suddenly, a number of taxonomies become potentially relevant: (i) the EU Taxonomy, as the bank is German; (ii) the Singapore Taxonomy, as the loan is booked at the Singapore subsidiary; (iii) the Indonesia Taxonomy, as there is an Indonesian investor; 8 Taxonomy governance structures for ASEAN, the EU, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. 32 (iv) the ASEAN Taxonomy, as the project is in ASEAN; and because the Japanese private equity firm has used the ASEAN Taxonomy as the internally approved benchmark for its ASEAN portfolio given that it uses the ASEAN Taxonomy rather than assessing investments on a country-by-country taxonomy basis; and (v) the German bank’s in-house taxonomy. A frequently asked question is which taxonomy will take precedence or be applied. Clearly, taxonomies that are mandatory and have the force of the law will need to be complied with. In this case, for the German bank, that would be the EU Taxonomy. The Singapore subsidiary would report under the Singapore Taxonomy and the Indonesian investor would report under the Indonesia Taxonomy. In the meantime, the Japanese private equity firm would use the ASEAN Taxonomy in assessing its investment criteria. This means everyone can and will use a different taxonomy to meet their needs, and the taxonomy used should be that which each of the parties voluntarily applies or is required to comply with on an individual basis. So where will a problem arise when multiple taxonomies are involved? The challenge arises when the project fits into some taxonomies and not others. It also creates additional work for all the parties involved as each party would need to evaluate every transaction individually and distinctly, without being able to rely on a standardized classification. It also means the project owner, in configuring the project, would need to take into consideration all the different capital providers’ needs, a task made more difficult in situations where the funders have yet to be determined. In many situations, the project financing structure may be less complex but cross border finance flows means there will also be the reality of multiple taxonomies, which while surmountable, adds to cost, time, and decreases the ease of raising finance. This situation can lead to a disincentive to finance as well as confusion. Interoperability has been put forth as a potential solution to making the process more efficient and effective. However, effective interoperability requires taxonomy designs to be compatible. The International Platform for Sustainable Finance published the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT), which sought to compare and map commonalities between the EU Taxonomy against the PRC Catalogue in 2021(with an update in 2022). The Hong Kong, China Taxonomy builds upon this mapping and intends to be interoperable with the ASEAN Taxonomy as a regional taxonomy, and the CBI Taxonomy as a market-based taxonomy (Hong Kong Monetary Authority 2024a). The International Platform for Sustainable Finance had noted in an FAQ that the CGT’s comparison 33 and mapping provided its own set of challenges and required further analysis to complete, due to the inherent differences between the two taxonomies’ designs and approaches. HKMA had also noted that incorporating the entire CGT into the Hong Kong Taxonomy without any modification was not possible as the CGT included jurisdiction specific elements (HKMA 2024b). This highlights interoperability challenges between taxonomies of different designs. Even if taxonomies are interoperable from a design perspective, with compatible metrics, there is still a usability gap as different TSC and assessment thresholds would lead to different assessment outcomes. This means that an activity eligible under one taxonomy would have to be reassessed under another, and activities structured to be eligible under one taxonomy may not be under a different taxonomy. This makes global capital flows inefficient and cross border assessments inconvenient. There is also the possibility of disruptions to the intermediation of capital as financial institutions that raise capital from a jurisdiction using a taxonomy different from the jurisdiction they provide finance in, may find the asymmetry inhibiting their ability to intermediate capital when the jurisdictions they raise capital from have higher ambitions than the jurisdictions they provide finance in. As such, taxonomies need to move beyond interoperability toward equivalence. Equivalence means eligibility under one taxonomy can also be recognized under another taxonomy. This allows all stakeholders to understand clearly where specific pools of capital can flow to and for the capital users to respond appropriately. It is important to note that equivalence does not mean simply mapping two asymmetric TSC as equivalent as a matter of convenience. Such an approach would cause disruption and destroy the credibility of the more ambitious taxonomy. Ideally, taxonomies should share common design elements such as environmental objectives, activity classification, essential criteria such as DNSH and social aspects, as well as assessment frameworks that use the same metrics. It is equally important that taxonomy developers share the same guiding principles, such as adopting a science-based approach. Only by having common guiding principles and design elements can taxonomies be comparable and interoperable and eventually have equivalence. Significant work has been carried out by the ASEAN Taxonomy Board to enable alignment between the ASEAN Taxonomy with AMS national taxonomies and other widely used 34 international taxonomies such as the EU Taxonomy. A comparison of the key design elements, including thresholds for comparable activities, of the ASEAN Taxonomy and ASEAN national taxonomy classifications shows that the thresholds of the AMS national taxonomies can be mapped to a tier of the ASEAN Taxonomy and equivalence can be established. It should be pointed out that the ASEAN Taxonomy was designed to be the taxonomy of equivalence for the ASEAN region. The ASEAN Taxonomy and AMS national taxonomies are interoperable and comparable as they have similar design elements and metrics. AMS national taxonomies are either principles-based or TSC-based and the ASEAN Taxonomy applies to both frames. In some AMS national taxonomies, ASEAN Taxonomy TSC have also been adopted. The participation of AMS national taxonomy developers in the development of the ASEAN Taxonomy further fosters collaboration in ensuring interoperability, equivalence, and applicability across the region. This level of interoperability and equivalence allows the user to place reliance on the ASEAN Taxonomy. For example, where an activity is not covered under an AMS national taxonomy, the ASEAN Taxonomy can serve as a reference for activity assessment. The Green Tier of the ASEAN Taxonomy’s Plus Standard is referenced to the EU Taxonomy, ensuring that its Green Tier is the main equivalent and therefore, credible as a Green classification. Divergences from the EU Taxonomy made to accommodate regional circumstances have been catalogued by the ASEAN Taxonomy Board to ensure that variances can be justified. While differences still exist between the two taxonomies in areas such as RMT and the coverage of social safeguards, they are broadly interoperable, and equivalence can be established. Equivalence reduces the amount of assessment to be conducted and reduces friction to users in applying a taxonomy across the region or globally. B. Challenges in Developing and Implementing Taxonomies and Policy Approaches Challenges exist in creating a taxonomy, as well as in implementing it. Setting the North Star for a taxonomy is the first challenge. It is important to identify the primary purpose of the taxonomy and select the right taxonomy objectives. While this may sound easy, it is more complex in practice. They may also reflect national ambitions, not just in environmental goals but also economic and social goals. Balancing these goals can result in complications that may impact a taxonomy’s usefulness. The primary purpose of a taxonomy will influence its objectives. Taxonomies are a link between the financial sector and the real economy and need to be able to 35 engender a “whole of economy” approach. As such, there is a need to incorporate the input of all relevant stakeholders. Where a taxonomy has sectoral coverage, the views of the sectoral stakeholders need to be reflected to avoid misalignment. The level of granularity resulting from this reflection will need to be at the economic activity level as this is where the real economy is at work. Again, the stakeholders of each economic activity will vary—from the real economy participants, to providers of capital, to governments and civil society. Different stakeholders would have different goals and targets. This leads to the need for a significant amount of coordination, data gathering, and consensus building. Setting credible and robust science-based targets and pathways is not a straightforward task. Taxonomy development requires resources and political will. To make decisions on the taxonomy design, data is needed. Data is also needed for assessments under a taxonomy. Challenges exist on data availability, transparency, and verification (OECD Green Finance and Investment 2022). A taxonomy cannot be constructed without the right data, including relevant national data such as emissions data. In addressing sectoral assessments, sectoral data and economic activity data will be needed. However, as data challenges may take time to address, some jurisdictions have turned to using principles-based taxonomies as a starting point. The use of principles-based taxonomies has the benefit of preparing stakeholders to use a more sophisticated TSC-based taxonomy in the future, including in collecting data, while guiding economic activities into more alignment with the taxonomy objectives. However, as noted earlier, TSC-based taxonomies are needed to achieve specific targets, such as emissions reduction. Verification of data and assessments is also required to strengthen the value of taxonomy outputs. Capacity is another major challenge. This affects all taxonomy users—both capital providers and capital users. Organizational capacity needs to be strengthened for taxonomy use. This includes, again, collecting and interpreting data and taxonomy-related information. Navigating a taxonomy requires the right skills. It goes beyond looking at benchmarks but also making judgments about decision points such as DNSH and social aspects. Principles-based taxonomies require users to have the right skill sets to arrive at meaningful conclusions that are consistent and credible. Taxonomy reporting also requires systems and resources. Additionally, the capacity of the ecosystem, such as verifiers and assessors, as well as information providers, needs to be strengthened. 36 It is important to remember that taxonomies are only one part of the sustainable finance ecosystem. Applying the ASEAN approach to building a sustainable finance ecosystem, for a taxonomy to succeed, the other pillars of Transition Finance Frameworks and Disclosure also need to be strengthened. Taxonomies need to dovetail with the other ecosystem pillars for optimal impact. The lack of general infrastructure nationally to support the deployment of a taxonomy has resulted in most jurisdictions not making taxonomies mandatory. However, the adoption of voluntary taxonomies may be slower. When it comes to global capital flows, it is natural that a mandatory taxonomy will take precedence over a voluntary taxonomy. While the development and implementation of taxonomies face challenges today, these challenges will be overcome with time and experience. There are six key dimensions that are critical for a taxonomy’s success. These dimensions and the policy approaches that can support them are discussed below. (i) Dimension 1: Relevance. Taxonomies need to be relevant. For this to happen, they must clearly address a purpose and meet a need. As such, taxonomies need to tie into national goals and policies. These include decarbonization goals and pathways such as NDCs. Finance policymakers and regulators, while not the only official sector group capable of doing so, are well placed to lead the development and implementation of official taxonomies, as taxonomies deal with the orientation of capital. However, “whole of government” input and support is necessary given the pervasive impact of taxonomies. This means that the finance sector can form the nucleus for a taxonomy, but other parts of government, real economy participants, and other stakeholders need to be adequately involved. A strong signal from the official sector on the adoption of a taxonomy, even though not mandatory, is vital. Financial supervisors can ask for reporting based on taxonomy classifications for monitoring purposes and governments can use taxonomies to classify fiscal budget items and for incentives, which will encourage the market to follow suit. A robust taxonomy development governance process can help in ensuring a taxonomy’s relevance. 37 Financial institutions and other market participants can also develop taxonomies that are relevant to their areas of interest, leveraging on market discipline.9 (ii) Dimension 2: Comprehensiveness. Comprehensiveness refers to the coverage of the taxonomy. The more standalone and complete a taxonomy is, the more useful it is. A taxonomy also needs to include all the economic sectors that have significant impact and cover all the relevant the economic activities within those sectors. The TSC and the metrics used for screening must also be sufficiently comprehensive and granular to achieve the desired outcomes. For example, this requires a careful look where emissions intensity is used as opposed to absolute emissions, and direct emissions instead of lifecycle emissions. A taxonomy that looks at outcomes using TSC can deal with more situations than a Whitelist taxonomy, although a Whitelist taxonomy is straightforward to apply. Governments can help populate a taxonomy to ensure well-rounded coverage at a sufficiently granular level. This would involve ensuring support and cooperation from various parts of government to the taxonomy developers. (iii) Dimension 3: Usability. The success of a taxonomy hinges on it being adopted and used by stakeholders. A taxonomy needs to be credible yet simple enough to use. Taxonomy definitions need to be clear. This means that it is often better to specify criteria rather than to leave it open to interpretation. The inputs for assessment need to be readily available. A taxonomy is not usable if the inputs are difficult to acquire or are not reliable. At the same time, a taxonomy must be usable by its intended audience. Usability needs to take into consideration the readiness of the jurisdiction. The criteria set out in a widely used taxonomy may not be realistic under local conditions. In designing a taxonomy, this divergence needs to be taken into consideration with local nuances captured (e.g., importance of CPO in ASEAN) without undermining international credibility. In instances where there are divergences, it is important to demonstrate 9 The Climate Bonds Initiative Taxonomy is an example. 38 the science-based reasons for these divergences. An internationally interoperable taxonomy design will help facilitate interoperability. Mapping for equivalence, using a science-based approach, will further enhance the ability for capital to flow globally. From a policy perspective, taxonomies should be designed as far as possible to be globally interoperable and enable equivalence. As noted earlier, the ASEAN Taxonomy was designed to be a taxonomy of equivalence for AMS national taxonomies, and the current AMS national taxonomies are all able to achieve equivalence with the ASEAN Taxonomy. The ASEAN Taxonomy was designed to take into consideration the need for it to be able to be a conduit of equivalence for the taxonomies of the diverse AMS, resulting in its multitiered approach. (iv) Dimension 4: Robustness of ambition. The robustness of a taxonomy’s ambition is imperative for its credibility. Robustness refers to the ability of a taxonomy to meet its own, as well as global goals. Robustness is sometimes conflated with rigor. Rigor refers to the strictness of a taxonomy e.g., how stringent performance levels are set under a taxonomy. However, having more liberal performance levels does not necessarily mean that a taxonomy’s ambition is not robust. Taxonomies can start at, or allow for, lower performance levels and scale up ambition over time in line with the readiness of the jurisdiction. Here, it is critical that backloading and lock-ins of GHG emissions be avoided during the step-up period, and the scale-up should be sciencebased to enable the taxonomy goal to be achieved. The Transition taxonomies are an example of this. Taxonomy developers should ensure that taxonomies reflect the right level of ambition. For this, as a matter of policy, reference needs to be made to the global ambition, national goals and policies, and science-based pathways. (v) Dimension 5: Interoperability and equivalence. The need for interoperability was previously discussed. As noted, it is critical to pursue interoperability and equivalence. Most of the TSC-based taxonomies reviewed in this paper have referenced the EU Taxonomy. However, to contextualize for jurisdictional needs, additional classifications or different assessment criteria have been applied. 39 To increase interoperability, taxonomies should be as similar in design as possible. Selection of common assessment criteria will help enable equivalence. However, more official and proactive efforts to link taxonomies are needed. The International Platform for Sustainable Finance is an excellent platform for promoting interoperability. However, more bilateral and multilateral efforts should be encouraged. For example, the ASEAN Taxonomy has been recognized as an accepted taxonomy under the Abu Dhabi Global Market’s Sustainable Finance Regulatory Framework. It is also referenced in various taxonomies such as that of the Indonesia and the Philippines in setting assessment criteria and overall design. Interoperability and equivalence can be further promoted when taxonomy developers take an “adopt, adapt,10 or innovate” approach where taxonomies are developed based on other (widely used) taxonomies. Those widely used taxonomies can be adopted virtually wholesale or adapted to suit the jurisdiction’s needs (e.g., the South Africa and EU taxonomies). If adapting is not sufficient to achieve relevance and usability, then a taxonomy can be innovatively developed while referencing a widely used taxonomy (e.g., ASEAN Taxonomy and EU Taxonomy). (vi) Dimension 6: Future-proofed. As noted earlier, taxonomies must be able stand the test of time as sustainability journeys span over an extended period. However, during that period, there will be changes in the environment, technology, economic, and social conditions. As such, taxonomies need to be living documents that are maintained and reviewed throughout their lives. Engagement with stakeholders during the development of taxonomies and throughout their application, with relevant input being incorporated, is required. As taxonomies need to be designed to be future-proofed, from the start, it should build in mechanisms for effective reviews that also do not disrupt the market and stakeholders. For instance, as part of its taxonomy design, the ASEAN Taxonomy will have a Technical Review Board that will be responsible for reviewing and proposing enhancements to its Technical Screening Criteria. 10 The adopt and adapt concepts are not new. For instance, the International Financial Reporting Standards have been wholly adopted by various jurisdictions. The ASEAN Green Bond Standards are an adaptation of the Green Bond Principles of the International Capital Market Association. 40 VI. CONCLUSION Taxonomies play a key role in helping orient capital to advance the sustainability agenda, including for urgent climate change action. Taxonomies need to be useful but credible at the same time. There are different taxonomy approaches and taxonomies also incorporate jurisdictional conditions. This results in diversity in taxonomies. However, it is important for taxonomies to be interoperable and have equivalence to facilitate cross-border capital flows. Having common design characteristics helps interoperability, while adopting mappable TSC allows for equivalence. Taxonomies must be relevant, comprehensive, usable, have robustness in ambition, be interoperable and allow for equivalence, and be futureproofed. Taxonomies should be sciencebased where it is possible for credibility. The present challenges to the development and implementation of taxonomies include capacity, availability of data, and jurisdictional readiness. However, these should not stop the introduction of taxonomies as these challenges can be overcome with time and experience. 41 APPENDIX: ILLUSTRATION OF THE GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE OF FIVE TAXONOMIES ANALYZED Figure A1: ASEAN Taxonomy and European Taxonomy Development Governance Structures ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations, ATB= ASEAN Taxonomy Board, EU = European Union, DG FISMA = Directorate‑General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union, PSF = Platform on Sustainable Finance, TEG = Technical Expert Group, JRC = Joint Research Centre, CLIMA = Directorate-General for Climate Action, ENV = Directorate-General for Environment. Source: Institute for Sustainable Finance Canada. 2022. Taxonomy Governance: A Stocktake of International Examples. 42 Figure A2: Singapore Taxonomy and Malaysia Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy Governance Structures CCPT-IG = Climate Change and Principle-based Taxonomy Implementation Group, FAQs = Frequently Asked Questions, MAS = Monetary Authority Singapore, Source: Green Finance Industry Taskforce. 2023. Cultivating Singapore’s Sustainable Finance Ecosystem to Support Asia’s Transition to Net-Zero. Figure A3: Indonesia Taxonomy Governance Structure BI = Bank Indonesia, MOF = Ministry of Finance, NDC = nationally determined contribution, OJK = Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (Financial Services Authority of Indonesia), TKBI = Taksonomi untuk Keuangan Berkelanjutan Indonesia (Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance), TSC=Technical Screening Criteria. Source: Financial Services Authority of Indonesia (OJK). 43 SELECTED REFERENCES Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2023a. Asia in the Global Transition to Net Zero: Asian Development Outlook 2023 Thematic Report. ———. 2023b. Reinvigorating Financing Approaches for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure in ASEAN+3. ASEAN Taxonomy Board (ATB). 2023. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 2. ———. 2024. ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 3. AIFC. 2021. Kazakhstan Green Taxonomy. Bangladesh Bank. 2020. Sustainable Finance Policy for Banks and Financial Institutions. Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM). 2021. Climate Change and Principle-Based Taxonomy. Bank of Thailand (BOT). 2023. Thailand Taxonomy Phase 1. Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI). 2021. Climate Bonds Taxonomy. CBI, Climate Policy Initiative, and RMI. 2022. Working Paper: Guidelines for Financing a Credible Coal Transition—A Framework for Assessing the Climate and Social Outcomes of Coal Transition Mechanisms. European Commission. 2020. Taxonomy: Final Report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. E3G. 2022. Expanding Common Ground: Deepening International Cooperation on Taxonomies. Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). 2023. Financing the Managed Phaseout of Coal-Fired Power Plants in Asia Pacific. Green Finance Industry Taskforce. 2023. Cultivating Singapore’s Sustainable Finance Ecosystem to Support Asia’s Transition to Net-Zero. Green Technical Advisory Guide (GTAG). 2023. Treatment of Green Financial Products Under an Evolving UK Green Taxonomy. Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA). 2024a. Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. ——— 2024b. Hong Kong Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance: Consolidating the Green Finance Ecosystem. International Energy Agency (IEA). 2021. It’s Critical to Tackle Coal Emissions. ———. 2022a. Key Findings—Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2022. ———. 2022b. Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2022. Institute for Sustainable Finance. 2022. Taxonomy Governance: A Stocktake of International Examples. Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). 2023. Singapore-Asia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. 44 Ministry of Finance and Public Credit Mexico. 2023. Sustainable Taxonomy of Mexico. The Ministry of Environment of Korea. 2021. The Korean Green Taxonomy (K-Taxonomy). Mongolian Sustainable Finance Association (MFSA). Mongolia’s Sustainable Finance Journey & SDG Taxonomy. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. ———. 2019. Mongolia Green Taxonomy. National Treasury, Republic of South Africa. 2022. South African Green Finance Taxonomy 1st Edition. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2020. Developing Sustainable Finance Definitions and Taxonomies. ———. 2022. Guidance on Transition Finance: Ensuring Credibility of Corporate Climate Transition Plans, Green Finance and Investment. Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK). 2022. Indonesia Green Taxonomy Edition 1.0. OJK. 2024. Taksonomi Untuk Keuangan Berkelanjutan Indonesia (Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance). People's Bank of China. 2021. The Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2024. Guidelines on the Philippine Sustainable Finance Taxonomy. Securities Commission. 2022. SC Unveils Principles-Based Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy for the Malaysian Capital Market. 12 December. United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). 45