Uploaded by

common.user123582

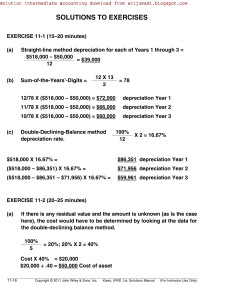

Chapter 11 Depreciation Impairments Depletion Solutions Manual

advertisement