Uploaded by

Irna Megawaty

Frequency of Methamphetamine Use and Cardiomyopathy Severity in Adults ≤50 Years

advertisement

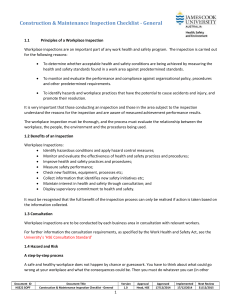

Frequency of Methamphetamine Use as a Major Contributor Toward the Severity of Cardiomyopathy in Adults £50 Years Michael M. Neeki, DO, MSa, Michael Kulczycki, DOa, Jake Toy, BAb, Fanglong Dong, PhDb, Carol Lee, MDa, Rodney Borger, MDa, and Sasikanth Adigopula, MDc,* Methamphetamine is one of the most commonly abused illegal drugs in the United States. Health care providers are commonly faced with medical illness caused by methamphetamine. This study investigates the impact of methamphetamine use on the severity of cardiomyopathy and heart failure in young adults. This retrospective study analyzed patients seen at Arrowhead Regional Medical Center from 2008 to 2012. Patients were between 18 and 50 years old. All patients had a discharge diagnosis of cardiomyopathy or heart failure. The severity of disease was quantified by left ventricular systolic dysfunction: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction to mildly reduced if ejection fraction was >40% and moderate to severely depressed if ejection fraction was £40%. Methamphetamine abuse was determined by a positive urine drug screen or per documented history. Of the 590 patients, 223 (37.8%) had a history of methamphetamine use. More than half the population was men (n [ 389, 62.3%); 41% was Hispanic (n [ 243), 25.8% was Caucasian (n [ 152), and 27.8% was African-American (n [ 164); 60.9% were in the age range of 41 to 50 years (n [ 359). Patients with a history of methamphetamine use had increased odds (odds ratio [ 1.80, 95% confidence interval 1.27 to 2.57) of having a moderately or severely reduced ejection fraction. Additionally, men were more likely (odds ratio 3.13, 95% confidence interval 2.14 to 4.56) to have worse left ventricular systolic dysfunction. In conclusion, methamphetamine use was associated with an increased severity of cardiomyopathy in young adults. Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. (Am J Cardiol 2016;118:585e589) Although there are extensive published reports on the cardiovascular pathophysiology, psychological effects, and behavioral effects of methamphetamine use, there is limited evidence pertaining to the development of early heart failure among users.1,2 We investigate the association of methamphetamine use and a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy or heart failure in adults 50 years. To our knowledge, this is the largest clinical study investigating this association. A previous study described this association in native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander populations and showed methamphetamine use to be an independent risk factor for cardiomyopathy or heart failure. The ethnic demographics for that study population was largely limited by geography.3 This study includes a large sample size and a diverse demographic in an urban tertiary care center located in San Bernardino County, California. a Department of Emergency Medicine, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, California; bWestern University of Health Sciences, College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Pomona, California; and cDepartment of Cardiology, Advanced Heart Failure and Heart Transplantation, Loma Linda University Medical Center, Loma Linda, California. Manuscript received March 7, 2016; revised manuscript received May 7, 2016; accepted May 23, 2016. See page 588 for disclosure information. *Corresponding author: Tel: 7087900512; fax: 9095580309. E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Adigopula). 0002-9149/16/$ - see front matter Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.05.057 Methods This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Arrowhead Regional Medical Center (ARMC) and was a retrospective chart review study. ARMC is a 456-bed acute care teaching facility and one of the 2 American College of Surgeonsecertified level II trauma centers located in San Bernardino County, California.4 San Bernardino County is the largest county in the contiguous United States and has an estimated population of 2,091,618 in 2014. The predominant ethnicity is Latino at 51%. Among non-Latino residents, 31% are white, 8% are African-American, 7% are Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3% reported as 2 races or American Indian/Alaska Native or other.5 Emergency department patients seen at ARMC from January 2008 to December 2012 were analyzed for inclusion in this study. Patients were selected from both genders and all ethnicities. Patients were included if they were 18 to 50 years old and had a discharge diagnosis of cardiomyopathy or heart failure. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes were used to select patients with a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy (ICD-9: 425.2 to 425.9) or heart failure (ICD-9: 428.0 to 428.9). Methamphetamine use was determined by a positive urine drug screen or by documentation in the patient’s chart by the physician. Patients with a history of coronary artery disease or valvular heart disease were excluded from the multivariate logistic regression. Among women, patients who were www.ajconline.org 586 The American Journal of Cardiology (www.ajconline.org) Table 1 Patient demographic information Variable Female Male Black Hispanic Other White Age (years) 18-30 31-40 41-50 Methamphetamine Use Tobacco Use Alcohol Use Cocaine Use Marijuana Use Diabetes Mellitus Hypertension Dyslipidemia Ejection Fraction >40% 40% Figure 1. A retrospective extensive chart review was performed, and 862 patients with a history of cardiomyopathy were identified. Patients who did not have documented EF and patients who had other reasons to have cardiomyopathy (coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, and peripartum cardiomyopathy) were excluded. suspected to have peripartum cardiomyopathy were excluded regardless of methamphetamine use. For patients with multiple admissions, only data from the initial visit were recorded and repeat hospitalizations were excluded. The primary outcome was the severity of LV systolic dysfunction as characterized by ejection fraction (EF) reduction. For study purposes, EF reduction severity, as determined by an echocardiogram, was categorized as follows: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) to mildly reduced EF >40% and moderately to severely reduced EF 40%. Selection of 40% as a baseline for clinically significant LV systolic dysfunction was based on its predictive value of cardiovascular outcome and indication for specific treatment protocols.6e11 Analyzed predictors included age, ethnicity, methamphetamine use, tobacco use, alcohol use, cocaine use, marijuana use, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Ethnicity was further categorized into 4 groups: Hispanic, Caucasian, African-American, and other. Substance use Frequency (N¼590) Percent 228 362 164 242 32 152 (39%) (61%) (28%) (41%) (5%) (26%) 57 174 359 223 313 254 50 98 216 452 255 (10%) (30%) (61%) (38%) (53%) (43%) (9%) (17%) (37%) (77%) (43%) 367 223 (62%) (38%) history and the presence of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were obtained through chart review. All data were analyzed using the SAS software for Windows, version 9.3 (Cary, North Carolina). Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. A chi-square crosstab analysis was conducted to assess the association between predictors and severity of EF reduction (mild vs moderate to severe). A logistic regression was conducted using PROC LOGISTIC to identify factors associated with the severity of EF reduction (mildly vs moderately to severely reduced EF). The possible predictor included in the logistic regression included all the significant variables identified by the crosstab analysis. All statistical analyses were 2 sided; p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results A total of 862 patients with a discharge diagnosis of cardiomyopathy or heart failure were identified and assessed for inclusion in the study. Patients who lacked a noted EF in their chart (n ¼ 238), who had a history of peripartum cardiomyopathy (n ¼ 4), and who had a history of CAD or valvular heart disease (n ¼ 30) were excluded; 590 patients were included in the final analysis (Figure 1 for patients flow chart). The demographic information is presented in Table 1. More than half the population were men (61%); they were Hispanic (41%), Caucasian (26%), or AfricanAmerican (27%) and within the age range of 41 to 50 (61%). Of the 590 patients, 223 had associated methamphetamine use, which represented 38% of our study population. There was a significant correlation between the prevalence of methamphetamine use and ethnicity (Table 2). Patients aged 41 to 50 years were the most likely to use methamphetamine. Men were more likely than women to use Cardiomyopathy/Methamphetamine Use and Cardiomyopathy Severity Table 2 Crosstab analysis of methamphetamine use by demographic variables within the study population* Variable Methamphetamine Use No (n¼367) Table 3 Crosstab analysis of factors associated with levels of ejection fraction Variable P-value Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction >40% (n¼367) 40% (n¼223) Female Male 177 (78%) 190 (53%) 51 (22%) 172 (48%) Black Hispanic Other White Age (years) 18-30 31-40 41-50 Methamphetamine Use Tobacco Use Alcohol Use Cocaine Use Marijuana Use Diabetes Mellitus Hypertension Dyslipidemia 98 155 19 95 (60%) (64%) (59%) (63%) 66 87 13 57 (40%) (36%) (41%) (38%) 30 110 227 119 177 151 31 58 131 285 163 (53%) (63%) (63%) (53%) (57%) (60%) (62%) (59%) (61%) (63%) (64%) 27 64 132 104 136 103 19 40 85 167 92 (47%) (37%) (37%) (47%) (44%) (41%) (38%) (41%) (39%) (37%) (36%) Yes (n¼223) Age (years) 18-30 31-40 41-50 38 (67%) 119 (68%) 210 (59%) 19 (33%) 55 (32%) 149 (42%) Female Male 148 (65%) 219 (61%) 80 (35%) 143 (40%) Black Hispanic Other White 128 153 27 59 0.8295 0.2815 <.0001 36 89 5 93 P-value <.0001 0.0667 (78%) (63%) (84%) (39%) 587 (22%) (37%) (16%) (61%) * The total row percentage may not add up to 100% due to rounding. methamphetamine. More than half (61%) of the Caucasians in the study population were methamphetamine users, followed by Hispanics and African-Americans. Table 3 presents the analysis of various factors associated with the severity of cardiomyopathy among these patients. Patients with a history of methamphetamine use were at a greater risk of having a moderate to severely reduced EF (47% vs 32%, p ¼ 0.0006). Additionally, men were more likely to have moderate to severely reduced EF compared with women (48% vs 22%, p <0.0001). Tobacco users in comparison with non-tobacco users had a moderate to severely reduced EF (44% vs 31%, p ¼ 0.0026). Other factors, including ethnicity, age, alcohol use, cocaine use, marijuana use, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, were not statistically significantly associated with EF severity among the cardiomyopathy patients. Methamphetamine use, gender, and tobacco use were further analyzed for the association with the severity of cardiomyopathy from a multivariable logistic analysis perspective. The results are presented in Table 4. Compared with patients without a history of methamphetamine use, patients with a history of methamphetamine use were more likely to experience moderate to severely reduced EF (adjusted odds ratio ¼ 1.80, 95% confidence interval 1.27 to 2.57). Moreover, men showed a greater risk than women to experience moderate to severely reduced EF (adjusted odds ratio ¼ 3.13, 95% confidence interval 2.14 to 4.56). Tobacco use was significantly associated with the severity of cardiomyopathy at the univariate level but no longer when adjusted for methamphetamine use and gender. Discussion The present study showed that 38% of patients with cardiomyopathy had associated methamphetamine use. These patients with a history of methamphetamine use were at a greater risk for a more severe form of cardiomyopathy or heart failure in comparison with nonusers. Furthermore, our findings show that methamphetamine use was an independent risk factor for an increase in the 0.2925 0.0006 0.0026 0.2302 0.9753 0.4996 0.5538 0.4411 0.4527 Table 4 Prediction of moderately or severely reduced ejection fraction using logistic regression* Variable Methamphetamine Use (yes vs no) Male vs female Tobacco Use (yes vs no) Unadjusted Odds Ratio Adjusted Odds Ratio 1.82 (1.29, 2.56) 1.80 (1.27, 2.57) 3.14 (2.16, 4.57) 0.59 (0.43, 0.84) 3.13 (2.14, 4.56) * Predictor included in the ordinal logistic regression include: Methamphetamine Use (yes vs no), gender (male vs female), and Tobacco use (yes vs no). Only gender and methamphetamine use were significant predictors for the adjusted odds ratio estimate. severity of cardiomyopathy and heart failure. To our knowledge, this is the first cohort study addressing this association in the contiguous United States. Our findings build on an increasing pool of evidence elucidating the correlation between methamphetamine use and a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy or heart failure in adult patients 50 years. Our study also established that this relation exists across multiple ethnic groups and geographical regions.3 Additionally, the results of our study demonstrated that men were more likely to develop a severe form of cardiomyopathy than women. The difference is likely because of an increased prevalence of methamphetamine use in men within the study population. In this study, patients with cardiomyopathy did not have a positive association with cocaine use. The low prevalence of cocaine use in our study population (8%) could have been a contributing factor. This finding was also noted in a previous study analyzing cardiomyopathy and methamphetamine use.3 588 The American Journal of Cardiology (www.ajconline.org) In adults 50 years with heart failure, methamphetamine associated cardiomyopathy is increasing in prevalence in the United States and requires a team-based approach for effective management. This would include cardiologists, primary care physicians, emergency physicians, mid-level practitioners, psychiatrists, social workers, and drug addiction specialists working together to control this rising epidemic. From previous studies, it is recognized that the cardiomyopathy associated with methamphetamine use appears to be potentially reversible on cessation of methamphetamine.2,12e16 However, the exact window of reversibility, the degree of reversibility, and the incidence of reversibility are unclear. A previous study demonstrates that patients with methamphetamine-associated severe cardiomyopathy can make a full recovery after discontinuation of methamphetamine with no lasting fibrosis as determined through cardiovascular magnetic resonance.17 Removal of a pheochromocytoma to reverse severe cardiac dysfunction has been well described.18e21 It appears that improvement of cardiac function, after the discontinuation of methamphetamine, may act through a similar mechanism with the return of catecholamine levels to normal. The plausibility that methamphetamine-associated cardiomyopathy can be reversed has serious medical and social implications. Early detection is extremely important. The selection of an EF 40% as a baseline for clinically significant left ventricular systolic dysfunction was based on current guidelines.6 Although it is recognized that methamphetamine-associated cardiomyopathy predominantly presents as heart failure with reduced EF with an EF 40%, its likelihood to present as HFpEF or as mild LV systolic dysfunction has not been well studied. The likelihood of hospitalization and risk of death due to heart failure is strongly correlated with an EF 40%.9 Because methamphetamine use is correlated with severe cardiomyopathy, users are at an increased risk for adverse medical outcomes and for need of expensive drug and device therapy. Selection of patients between the ages of 18 and 50 was based on data demonstrating a decreased prevalence of agerelated ischemic cardiomyopathy in this demographic.22 Inclusion of all age groups would have increased the applicability of our findings to the general population. However, inclusion of subjects >50 years could have presented as a confounding factor in determining if methamphetamine was an independently associated risk factor for worsened cardiomyopathy. A significantly larger sample size would be required to identify this. There were a number of limitations in our study. We were only to able collect data from hospitalized patients with cardiomyopathy at a single tertiary care center. Nonhospitalized patients with mild or subclinical cardiomyopathy could not be included. As a result, our study population represents only a subset of patients with a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy and associated methamphetamine use, particularly those with a severe form of cardiomyopathy. The primary diagnostic measure was limited to echocardiogram as many patients seen in the emergency department at ARMC do not undergo further workups. We were also unable to assess the duration of methamphetamine use as a risk factor for developing cardiomyopathy as data were only collected from the initial hospital visit. However, positive urine toxicology was complemented by physician documentation of a history of chronic methamphetamine use. A second limitation was the categorization of the severity of a patient’s cardiomyopathy solely through EF. This does not allow us to quantify the severity of heart failure in those patients with HFpEF. However, previous studies indicate that methamphetamine-associated cardiomyopathy often presents as dilated cardiomyopathy with a reduced EF.2,16 Additional studies are warranted to elucidate the exact clinical manifestations and pathophysiology of methamphetamine-induced HFpEF. Another limitation is the possibility that methamphetamine users may be less compliant with medications and dietary recommendations, thus increasing their risk of severe cardiomyopathy. However, nonadherence to medications has varied widely among many studies in heart failure. Our study highlights cardiomyopathy and heart failure that is likely related to methamphetamine use. A final limitation was that data for this study were gathered through a retrospective review of hospital records at a single tertiary care center increasing the likelihood for selection bias. Toxicology screening is not routinely performed on all patients. It is also possible that some practitioners did not investigate substance abuse history in detail, particularly with respect to methamphetamine. Patients may also be hesitant to disclose a history of methamphetamine use. These factors have the potential to alter the prevalence of methamphetamine use and association of the demographic variables in the study population. Acknowledgment: The authors would like to acknowledge Jonathan Lee, RN, MSN, and Massoud Rabiei, BS, for assisting with the initial data collection and database compilation. Disclosures The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. 1. Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A. Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by the amphetamines: a review. Prog Neurobiol 2005;75:406e433. 2. Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J, Darke S. Methamphetamine and cardiovascular pathology: a review of the evidence. Addiction 2007;102: 1204e1211. 3. Yeo KK, Wijetunga M, Ito H, Efird JT, Tay K, Seto TB, Alimineti K, Kimata C, Schatz IJ. The association of methamphetamine use and cardiomyopathy in young patients. Am J Med 2007;120:165e171. 4. Lee C, Walters E, Borger R, Clem K, Fenati G, Kiemeney M, Seng S, Yuen HW, Neeki MM, Smith D. The San Bernardino, California, terror attack: two emergency departments’ response. West J Emerg Med 2016;17:1e7. 5. Ramos J. San Bernardino County Community Indicators Report 2015; San Bernardino County, CA 2015:1e73. Available at: http://cms. sbcounty.gov. Accessed March 5, 2016. 6. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL; American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of Cardiomyopathy/Methamphetamine Use and Cardiomyopathy Severity 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147ee239. Heart Failure Society of America; Lindenfeld J, Albert NM, Boehmer JP, Collins SP, Ezekowitz JA, Givertz MM, Katz SD, Klapholz M, Moser DK, Rogers JG, Starling RC, Stevenson WG, Tang WH, Teerlink JR, Walsh MN. HFSA 2010 comprehensive heart failure practice guideline. J Card Fail 2010;16:e1ee194. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Køber L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Rønnevik PK, Rutten FH, Seferovic JSP, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787e1847. Solomon SD, Anavekar N, Skali H, McMurray JJV, Swedberg K, Yusuf S, Granger CB, Michelson EL, Wang D, Pocock S, Pfeffer MA; Candesartan in Heart Failure Reduction in Mortality (CHARM) Investigators. Influence of ejection fraction on cardiovascular outcomes in a broad spectrum of heart failure patients. Circulation 2005;112: 3738e3744. Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moyé LA, Basta L, Brown EJJ, Cuddy TE, Davis BR, Geltman EM, Goldman S, Flaker GC. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N Engl J Med 1992;327: 669e677. Flather MD, Yusuf S, Køber L, Pfeffer M, Hall A, Murray G, TorpPedersen C, Ball S, Pogue J, Moyé L, Braunwald E. Long-term ACEinhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 589 ACE-Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Lancet 2000;355:1575e1581. Wijetunga M, Seto T, Lindsay J, Schatz I. Crystal methamphetamineassociated cardiomyopathy: tip of the iceberg? J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2003;41:981e986. Won S, Hong R, Shohet RV, Seto TB, Parikh NI. Methamphetamineassociated cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol 2013;36:737e742. Jacobs LJ. Reversible dilated cardiomyopathy induced by methamphetamine. Clin Cardiol 2013;12:725e727. Simpson LL. Blood pressure and heart rate response evoked by d- and l- amphetamine in the pithed rat preparation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1975;193:149e159. Islam MN, Kuroki H, Hongcheng B, Ogura Y, Kawaguchi N, Onishi S, Wakasugi C. Cardiac lesions and their reversibility after long term administration of methamphetamine. Forensic Sci Int 1995;75:29e43. Lopez JE, Yeo K, Caputo G, Buonocore M, Schaefer S. Recovery of methamphetamine associated cardiomyopathy predicted by late gadolinium enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2009;11:46. Elian D, Harpaz D, Sucher E, Kaplinsky E, Motro M, Vered Z. Reversible catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy presenting as acute pulmonary edema in a patient with pheochromocytoma. Cardiology 1993;83:118e120. Satendra M, Jesus C, Bordalo AL, Rosário L, Rocha J, Castelo HB, Correia MJ, Diogo AN. Reversible catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy due to pheochromocytoma: case report. Rev Port Cardiol 2014;33:e1ee6. Wiswell JG, Crago RM. Reversible cardiomyopathy with pheochromocytoma. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 1969;80:185e195. ter Bekke RM, Crijns HJ, Kroon AA, Gorgels AP. Pheochromocytoma-induced ventricular tachycardia and reversible cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2011;147:145e146. Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011;8:30e41.