Uploaded by

common.user36758

Incidence and Risk Factors of PPROM in Singleton Pregnancies

advertisement

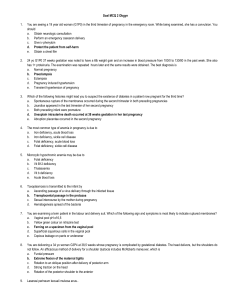

doi:10.1111/jog.13886 J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2018 Incidence and risk factors of preterm premature rupture of membranes in singleton pregnancies at Siriraj Hospital Phatsorn Sae-Lin and Prapat Wanitpongpan Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand Abstract Aim: To obtain the incidence of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) at Siriraj Hospital during 2012–2016 and to identify its possible risk factors in singleton pregnancies. Methods: This study was a retrospective case–control study. The institutional ethical committee has approved the study. The medical records of eligible cases were reviewed. To assess the risk factors of PPROM, the data of the cases with PPROM in 2016 were compared with the data of pregnant women who did not have PPROM and delivered at term. Fifteen variables of interest were studied. Results: During the 5-year period, there were 43 727 deliveries at Siriraj Hospital and 1280 (2.93%) cases had PPROM. In 2016, 252 pregnant women were diagnosed PPROM and data of 199 cases were compared with the data of 199 control cases. Mean latency period was 2 days and mean gestational age at birth was 34.7 weeks in PPROM group. Logistic regression analysis showed that diabetes mellitus, poor weight gain and history of previous preterm birth were the factors that significantly associated with PPROM, with adjusted odds ratio (OR) 3.22 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.47–7.05), 2.58 (95% CI 1.63–4.07) and 8.81 (95% CI 2.81–28.69), respectively (P < 0.05), while multiparity decreased the risk of PPROM (adjusted OR = 0.36, 95% CI 0.23–0.57) (P < 0.001). Conclusion: The incidence of PPROM during 5-year period was 2.93%. Diabetes mellitus, poor maternal weight gain and history of previous preterm birth significantly increased risk of PPROM while multigravida reduced the risk. Key words: incidence, poor weight gain, preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membrane, risk factor. Introduction Preterm delivery is the leading cause of perinatal morbidities, mortalities and long-term neurodevelopmental impairment. One-third of preterm deliveries are the result of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM). The incidence of this condition varies from 3% to 5% of all pregnancies.1–4 PPROM is a pathological condition that results in premature weakening and rupture of fetal membranes before onset of labor.5,6 The etiology of PPROM appears to be multifactorial and includes many demographic and clinical factors, such as smoking, low socioeconomic status, previous preterm birth, excessive membrane stretching, connective tissue disorders, prior cervical surgery and, importantly, choriodecidual infection.7–14 The leakage of amniotic fluid will expose the intrauterine fetus to many harmful conditions, such as intrauterine infection, hypoxia as a result of compression or prolapse of umbilical cord, placental abruption and postnatal complications related to prematurity.5,6 Shortly after the rupture of fetal membranes, spontaneous labor will ensue in most cases and this will lead to neonatal morbidities or mortality Received: September 4 2018. Accepted: November 24 2018. Correspondence: Dr Prapat Wanitpongpan, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10700, Thailand. Email: [email protected] © 2018 Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1 P. Sae-Lin and P. Wanitpongpan if PPROM occurs at very early gestation. It seems that many preventive and therapeutic strategies to improve perinatal outcomes have not achieved satisfactory impacts and PPROM still remains one of the most challenging problems in modern obstetrics. This study was carried out to determine the recent incidence of PPROM in tertiary hospital and its risk factors, with the hope to gather information to develop proper antenatal care to improve the perinatal outcomes. have PPROM and delivered at term were used as control. The demographic data was analyzed by descriptive statistics using PASW statistics 18.0 (SPSS Inc.). The continuous data was expressed by mean standard deviation, while the categorical data was expressed by percentage. Student t-test and chi-square test were used to compare the continuous and categorical data between the two groups. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors that were significantly associated with PPROM. P value less than 0.05 was used to define statistical significance. Methods This study was a retrospective case–control study. After the institutional ethical committee has approved the study, electronic medical records of pregnant women who delivered at Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, during January 2012–December 2016 were reviewed to obtain the incidence of PPROM. Informed consents from each patient were not obtained because of the retrospective nature of the study. PPROM was defined as a condition that the fetal membranes ruptured before the onset of labor before 37 weeks of gestation. The diagnosis of rupture of fetal membranes was established by history, physical examination and laboratory study. A history of spontaneous leakage of substantial amount of fluid, pool of amniotic fluid in vaginal fornix that was visible by the use of dry and clean vaginal speculum or positive fern test could confirm the diagnosis.15 Gestational age was determined by correct menstrual history or crown-lump length measurement in the first trimester. The PPROM cases in 2016 were recruited for assessment of associated risk factors. Demographic information and 15 parameters of interest were retrieved and recorded in case record form. The 15 parameters included age, socioeconomic status, urinary tract infection (UTI) during pregnancy, parity, prepregnancy body mass index, weight gain during pregnancy, history of previous preterm birth, history of abortion, smoking, alcohol drinking, hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus (DM), threatened abortion, amniocentesis and presence of sexually transmitted diseases (STD) during pregnancy (detail information is presented in Appendix S1, Supporting Information). Exclusion criteria were multifetal pregnancies, uncertain gestational age, abnormal fetal chromosome or fetal malformation, previous cervical surgery and the presence of therapy with progesterone in studied pregnancy. Data of pregnant women who did not 2 Results During the 5-year period there was a total of 43 727 deliveries in Siriraj Hospital and there were 1280 cases (2.93%) of PPROM. In the year 2016, there were 252 cases of PPROM and 199 cases of them were eligible for the study. The demographic data and clinical factors of the two groups were shown in Table 1. Basic characteristics of the two groups were not statistically different. Mean latency period was 2 days and mean gestational age at birth was 34.7 weeks in PPROM group. Only DM, hypertensive disorders, parity, poor weight gain and previous preterm birth were selected for further multivariate analysis. The results of logistic regression analysis were shown in Table 2. The parameters that were significantly associated with PPROM were DM (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.22, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.47–7.05), poor weight gain (adjusted OR 2.58, 95% CI 1.63–4.07) and previous preterm birth (adjusted OR 8.81, 95% CI 2.81–28.69). Multiparity significantly decreased the risk of PPROM (adjusted OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.23–0.57) (P < 0.001) (Table 3). Discussion The incidence of PPROM in our study is the same as the previous studies.1–4 The incidence seems to be stable over time and is unlike that of indicated preterm birth which seems to be increasing due to advanced maternal age, more cases of pregnancy with existing medical disorders and increased number of pregnancies by assisted reproductive technique. The stable incidence of PPROM might more or less relieve the tension among obstetric care providers because PPROM is somehow more difficult to manage than © 2018 Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology Incidence and risk factors of PPROM Table 1 Clinical parameters of the two groups Clinical parameters Age (years) Alcohol drinking Amniocentesis Diabetes mellitus Hypertensive disorders Family income (Baht) Parity 0 ≥1 Poor weight gain Prepregnancy BMI Pregnancy outcomes GA at ROM (days) GA at delivery (days) Birthweight (g) Cesarean section Previous abortion Previous preterm birth Smoking STD during pregnancy Threatened abortion UTI during pregnancy PPROM group (n = 199) Control group (n = 199) 30.7 6.2 1/199 (0.5%) 39/154 (25.3%) 28/199 (14.1%) 24/199 (12.1%) 38 594 2991 1 (0–6) 135 (67.8%) 64 (32.2%) 85/199 (42.7%) 22.8 4.8 30.1 6.3 4/199 (2%) 39/182 (21.4%) 11/199 (5.5%) 18/199 (9%) 39 594 2858 2 (0–5) 104 (52.3%) 95 (47.7%) 48/199 (24.1%) 22.4 4.3 241 7 243 14 2397 545 39.7% 42/199 (21.1%) 16/199 (8%) 2/199 (1.0%) 6/144 (4.2%) 8/144 (5.5%) 4/144 (2.8%) 272 7 272 7 3118 405 53.7% 46/199 (23.1%) 4/199 (2%) 4/199 (2.0%) 11/181 (6.1%) 10/181 (5.5%) 1/181 (0.6%) P value 0.813 0.372 0.438 0.006 0.415 0.838 0.002 <0.001 0.256 NA 0.717 0.010 0.685 0.617 1.0 0.176 BMI, body mass index; GA, gestational age; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membranes; ROM, rupture of membranes; STD, sexually transmitted diseases; UTI, urinary tract infections. Table 2 Multivariable logistic regression analysis Parameters Parity 0 ≥1 Diabetes mellitus Poor weight gain Previous preterm birth Hypertension Crude OR (95% CI) P value Adjusted OR (95% CI) P value 1.0 0.52 (0.35–0.78) 2.8 (1.35–5.79) 2.35 (1.53–3.6) 4.26 (1.4–12.99) 1.38 (0.72–2.63) 1.0 0.36 (0.23–0.57) 3.22 (1.47–7.05) 2.58 (1.63–4.07) 8.81 (2.81–28.69) 1.388 (0.62–2.63) <0.001* 0.002 0.006 <0.001 0.01 0.415 0.003* <0.001* <0.001* 0.503 *Statistically significant. and CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. Table 3 Parity, diabetes and poor weight gain between the two groups Parameters Nulliparous Diabetes Poor weight gain Nulliparous + DM Multiparous + DM Nulliparous + poor weight gain Multiparous + poor weight gain Nulliparous + DM + poor weight gain Multiparous + DM + poor weight gain PPROM Control P value 135 28 85 16 12 52 33 8 7 104 11 48 6 5 25 23 1 0 0.002 0.004 <0.001 0.028 0.083 <0.001 0.149 0.037 0.015 DM, diabetes mellitus; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membranes. preterm labor with intact membranes, especially at very early gestational age. Many previous studies reported the association between PPROM and many factors. The results of our study were both concordant © 2018 Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and discordant with those studies. Previous preterm birth, in concordant with other studies, remains the strongest risk factor of PPROM. In addition, we found an association between PPROM and DM during 3 P. Sae-Lin and P. Wanitpongpan pregnancy and between PPROM and poor weight gain. Diabetes during pregnancy may increase risk of infections and create adverse pregnancy outcomes. Infection at choriodecidual interface has been reported to result in weakening of fetal membranes and PPROM.16 Fetal macrosomia and polyhydramnios are common in pregnancy complicated with DM and lead to overstretching of the fetal membranes and premature rupture. It was unsurprising for our team to see diabetes as another significant factor of PPROM. Although infection has been accepted as a major risk factor of PPROM, many of previous preventive strategies by antibiotics seemed unsatisfactory and did not help to reduce the incidence.17,18 Further studies about the explicit pathogenic organisms might lead to effective prevention of PPROM in pregnancies complicated by diabetes. Our study did not stratify between overt DM and gestational DM because we believed that both conditions offered the same pathophysiologic processes to create the adverse effects. Poor weight gain during pregnancy is not rare. This condition might be a result of maternal poor nutrition, strenuous hard working, placental insufficiency or fetal growth restriction. Lacking of nutrients that are necessary for collagen production or lacking of vitamins and antioxidants to preserve the strength of fetal membranes could lead to premature weakening and rupture of the fetal membranes.12,19,20 Carrying heavy objects increases intra-abdominal pressure and could also play a role for this condition. Again, further studies about specific nutritional replacement therapy during antenatal period might improve the outcomes of PPROM in the future. In our study, some factors, such as UTI during pregnancy, smoking, threatened abortion, STD during pregnancy, were not agreeable with previous reports.7,11,13,14 Due to the small number of these cases in PPROM group (four cases with UTI, two cases with smoking, eight cases with threatened abortion, six cases of STD) and inability to retrieve the data completely, we did not think that our study had enough power to draw a conclusion about these factors. Cautions should be exercised in interpretation and implementation of the data of our study. Until the stronger evidences come up, we encourage the readers to follow the guidelines or prior evidences that had enough power and provide proper interventions to the patients accordingly. Multiparity was found to be associated with lower risk of PPROM. We had no idea about the exact mechanism to explain this finding, but we thought it 4 was possible that previous uneventful pregnancies and deliveries reflected the competent structures and functions of the uterus to maintain pregnancy to term. The strength of this study is providing the additional knowledge about risk factors of PPROM, which could lead to better antenatal care to reduce the incidence of this condition. However, the retrospective nature of the study appears to be a limitation of our study. Inability to completely retrieve the data of some parameters is also the other limitation. Acknowledgments The authors thank Associate Professor Dr Dittakarn Boriboonhirunsarn, Assistant Professor Dr Chulaluk Komoltri and Miss Julaporn Pooliam for their help in statistical analysis. Disclosure None declared. References 1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins – Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 172: Premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 128: e165–e177. 2. Committee on Practice Bulletin. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 188: Prelabor rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol 2018; 131: e1–e14. 3. Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ et al. The preterm prediction study: Prediction of preterm premature rupture of membranes through clinical findings and ancillary testing. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 183: 738–745. 4. Medina TM, Hill DA. Preterm premature rupture of membranes: Diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2006; 73: 659–664. 5. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL et al. Preterm labor. In: Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL et al. (eds). Williams Obstetrics, 24th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2014; 829–861. 6. Brian M, Mercer MD. Premature rupture of the membranes. In: Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams JD, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, Greene MF (eds). Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice, 7th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2014; 663–674. 7. Hackenhaar AA, Albernaz EP, da Fonseca TM. Preterm premature rupture of the fetal membranes: Association with sociodemographic factors and maternal genitourinary infections. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2014; 90: 197–202. 8. Guinn DA, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW, Thom E, Romero R. Risk factors for the development of preterm premature rupture of the membranes after arrest of preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 173: 1310–1315. © 2018 Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology Incidence and risk factors of PPROM 9. Faucett AM, Metz TD, DeWitt PE, Gibbs RS. Effect of obesity on neonatal outcomes in pregnancies with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 214: e1–e5. 10. Phupong V, Taneepanichskul S. Outcome of preterm premature rupture of membranes. J Med Assoc Thai 2000; 83: 640–645. 11. Kilpatrick SJ, Patil R, Connell J, Nichols J, Studee L. Risk factors for previable premature rupture of membranes or advanced cervical dilation: A case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194: 1168–1174. 12. Woods JR Jr. Reactive oxygen species and preterm premature rupture of membranes – A review. Placenta 2001; 22 (Suppl A): S38–S44. 13. Genovese C, Corsello S, Nicolosi D, Aidala V, Falcidia E, Tempera G. Alterations of the vaginal microbiota in the third trimester of pregnancy and pPROM. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2016; 20: 3336–3343. 14. Furman B, Shoham-Vardi I, Bashiri A, Erez O, Mazor M. Clinical significance and outcome of preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: Population-based study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2000; 92: 209–216. 15. Simhan HN, Canavan TP. Preterm premature rupture of membranes: Diagnosis, evaluation and management strategies. BJOG 2005; 112 (Suppl 1): 32–37. 16. Shim SS, Romero R, Hong JS et al. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 1339–1345. © 2018 Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology 17. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy to prevent preterm delivery: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148: 214–219. 18. Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Cliver SP, Copper R, Conner M. Interconceptional antibiotics to prevent spontaneous preterm birth: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194: 617–623. 19. Osaikhuwuomwan JA, Okpere EE, Okonkwo CA, Ande AB, Idogun ES. Plasma vitamin C levels and risk of preterm prelabour rupture of membranes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011; 284: 593–597. 20. Ghomian N, Hafizi L, Takhti Z. The role of vitamin C in prevention of preterm premature rupture of membranes. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2013; 15: 113–116. Supporting information Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site: Appendix S1. The definitions of the clinical factors of interest 5